August 21, 2020

R40 and a Hospital Stay covid-19: day 164 | US: GA | info | act

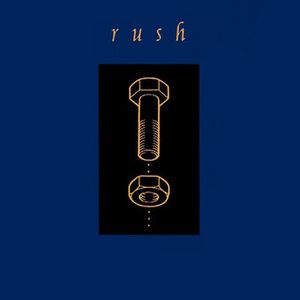

Tonight, I watched a bit of the Rush’s last tour, R40. Like Time Machine, they start with their latest material go back in time as the stage is deconstructed. They opened with “Anarchist”—an odd choice, I think—then went into “Headlong Flight.” The last time Autumn and I saw Rush live was for their Clockwork Angels tour, and one of the highlights of that show, for me, was “Headlong Flight”—maybe the best song on that album after “The Garden.” The nostalgia began there for me.

It’s still difficult to listen to Rush since Neil died. The band was (is!) such a major part of my life, that each of their albums brings up recollections of specific moments of my life. Sometimes it’s a loose association, but often it’s specific and concrete, as if the music brings the me of that time into sharper focus. I began to listen to them in the ’80s, probably beginning with Moving Pictures—I know that was the first CD I ever purchased, but surely I had the cassette way before that. Signals and Grace Under Pressure (probably my first cassette purchase on its release date in 1984 when I was but a green and awkward freshman) were big influences on my high school self, though I was listening to just as much Led Zeppelin at the time.

They played “Far Cry” off of Snakes & Arrows—again not my favorite from that album. I would have preferred “Faithless” or “The Way the Wind Blows.” “The Main Monkey Business” was strong, and they followed that with “How It Is” from Vapor Trails—a great choice, though my favorite is “Earthshine,” of course.

They skipped almost a decade, then, and I was transported to a hospital room in Tampa recovering from an appendectomy. I was living in a small, two-bedroom apartment wit my friend Nick at the time, finishing up my undergraduate degree at USF. My girlfriend would come up mid-week and stay a couple of nights; we’d go to classes during the day, and we’d all hang out at night watching our small television and drinking tea. Counterparts was released on October 19, 1993—a Tuesday, and I had gotten my CD that day, though I don’t remember if Christi was there or not—I don’t think she was. I remember getting up in the middle of the night with a stomach ache, and to distract myself, I sat in the beanbag in the living room listening to the new Rush on my CD Walkman. The sheer power of “Animate” just wowed me—Neil’s count-in, then groovy hammer of his drum line was joined by Geddy’s bass foundation and Alex’s distorted guitar added to the wave that washed me into the album. The whole album was good, but damn “Animate” was really good. This seemed to announce Rush’s return to a ’90s-tinged hard-rock roots, even before their prog-rock phase.

Counterparts got me through the night, but by sunrise I was in bad shape. I thought it might have been food poisoning, which I had experienced before, and I knew I just had to ride it out. This time, though, it had gotten worse. I must have drifted off, and when I awoke, I was nauseated, sweating, and and in more pain. I knew I had to do something. Some of this is a bit cloudy, but I guess Nick was already gone and Christi was not there, since I had to drive myself to the clinic. The USF clinic sent me to another on-campus facility. I remember sitting in the waiting room next to perky co-eds who were being called in before me. I knew I looked bad by this point, still sweating and likely a pasty pale, probably doing all I could to stifle groans.

They sent me to another place for a surgeon consultation. The waiting was interminable, and as soon as he performed a cursory examination, he said, “It looks like appendicitis.” I checked in to University Community Hospital—yes, I was still driving myself!—a bit later. I remember lying on a gurney outside the operating room; a nurse flubbed an initial attempt to insert an IV; the surgeon showed up and took over, deftly getting it done; “Count backwards from 100,” said someone above me who had just covered my mouth with a hissing mask under institutional florescent lights. I think I made it to 98.

“Cough for me.” A disembodied voice. A squareish florescent blur. I tried to cough, but the fire in my side convinced me to not try too hard. “C’mon, you can do better than that,” the voice urged. I coughed harder and immediately regretted it, pain overcoming me—not the dull, throbbing, sick pain I had experienced before, but a sharp, local one on my right side, a scalpel under the sutures. Tears further blurred the light. “There you go,” said the voice, and I thought You better not ask me to cough again.

I remember distinctly telling Christi not to bring the new Rush CD to the hospital, as I did not want to associate Rush with this event. It was October 20, 1993, and I was in my recovery room. Nick and Christi were waiting when I was wheeled in, still groggy from the anesthesia. They hooked up some sort of narcotic plunger system (Demerol, maybe?) to my IV, and a nurse explained that the button would respond every 15 minutes. I was uncomfortable, but glad my friends were there and releaved that I had made it through. I later found out from the surgeon, Dr. J. Sanders (now forever associated with “Nobody’s Hero”), that my appendix had actually burst and that they should have left the incision open because of that fact. Ugh, I thought, that sounds dreadful, secretly happy that they didn’t find out until I was sutured up. As a consequence, my stay at the hospital would be a bit longer—about a week.

I soon had my walkman (I was glad to have been ignored), and Counterparts helped me convalesce. My headphones on that old walkman leaked, I guess, because the guy they wheeled in after me (I was a poor college kid without insurance, so I was in a shared hospital room) complained that it bothered him. He was a whiny little bitch, and the nurses took pity on me and soon got me my own room to be rid of him. On one of the surgeon’s visits, he asked me if I’d urinated yet. I told him I hadn’t, but that I really haven”’t had anything to drink. “You’re getting plenty of liquid through that,” he said, nodding to the IV, “so you’ll need to go soon, or we’ll get a catheter in here.” The c-word provided the necessary motivation for my muscles to chill and let the pee out. My roommate wasn’t so lucky. The schadenfreude brought an evil little smile to my face as I listened to the male nurse insert a catheter in Mr. Too-Loud. I drowned his sobs with a bit more Rush: probably “Stick It Out.”

My mom came up from Bradenton with Christi. She stayed in my room and pissed Nick off by cleaning the apartment. “That place was pretty filthy,” she told me. “That’s probably how you got sick in the first place.” She might be right. We often had dishes piled up in the sink. We were young and busy with more important things. Clean dishes were unnecessary and quotidian until they were needed.

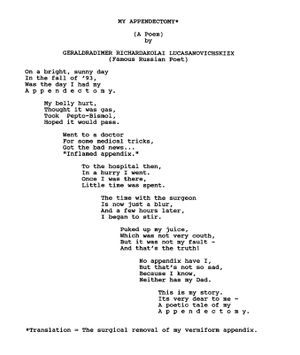

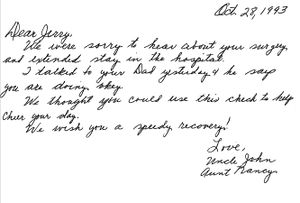

I soon received best-wishes from my family and professors. Dad sent me a poem, as he often did for special occasions. I was taking 19th-century Russian Literature at the time (Dad knew this, obviously), and I had to miss the discussion of Crime and Punishment which really bummed me out. Dr. Peppard knew this, and when I returned, we took some time to catch me up. That was great class, and I’m still friends with Vic Peppard to this day. Dr. Harmon, too, sent a note and her assurances that my “excellent” standing would likely remain unaffected.

Trauma has a way of leaving deep impressions in memory and anything that accompanies it is caught up in these grooves. I haven’t listen to Counterparts in a while, but “Animate” recalled this week almost thirty years ago—the soundtrack to my hospital stay. I probably didn’t need Rush to make it more vivid, but I certainly needed it to help me through.

The next song was “Roll the Bones,” and I have another memory of that, but it will have to wait.