More actions

m Added cat. |

m Added cat. |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

[[Category:Bibliographies]] | [[Category:Bibliographies]] | ||

[[Category:Lit Study Guides]] | [[Category:Lit Study Guides]] | ||

[[Category:Henrik Ibsen]] | |||

Latest revision as of 13:57, 11 April 2023

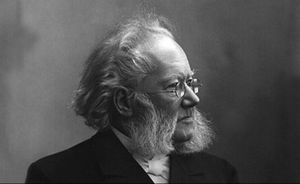

Notes on Ibsen

Ibsen’s Notes for the Modern Tragedy

Ibsen wrote these notes for A Doll’s House, showing his thinking about the societal differences between men and women. Since, he suggests, society is dominantly for men, the implications for Hedda Gabler are also apparent.

There are two kinds of spiritual law, two kinds of conscience, one in man and another, altogether different, in woman. They do not understand each other; but in practical life the woman is judged by man’s law, as though she were not a woman but a man.

The wife in the play ends by having no idea of what is right or wrong; natural feeling on the one hand and belief in authority on the other have altogether bewildered her.

A woman cannot be herself in the society of the present day, which is an exclusively masculine society, with laws framed by men and with a judicial system that judges feminine conduct from a masculine point of view.

She has committed forgery, and she is proud of it; for she did it out of love for her husband, to save his life. But this husband with his commonplace principles of honor is on the side of the law and looks at the question from the masculine point of view.

Spiritual conflicts. Oppressed and bewildered by the belief in authority, she loses faith in her moral right and ability to bring up her children. Bitterness. A mother in modern society, like certain insects who go away and die when she has done her duty in the propagation of the race. Love of life, of home, of husband and children and family. Now and then a womanly shaking off of her thoughts. Sudden return of anxiety and terror. She must bear it all alone. The catastrophe approaches, inexorably, inevitably. Despair, conflict, and destruction.

(Krogstad has acted dishonorably and thereby become well-to-do; now his prosperity does not help him, he cannot recover his honor.)[a]

Note

- ↑ Henrick Ibsen from “Notes for the Modern Tragedy.” Translated by A. G. Chater.

Bibliography

- Boyesen, Hjalmar Hjorth (1973) [1894]. A Commentary on the Works of Henrik Ibsen. New York: Russell and Russell.

- Brustein, Robert Sanford (1991). The Theatre of Revolt: An Approach to the Modern Drama. Chicago: Elephant Paperbacks.

- Bryan, George B. (1984). An Ibsen Companion: A Dictionary Guide to the Life, Works, and Critical Reception of Henrik Ibsen. Westport: Greenwood Press.

- Gray, Ronald D. (1977). Ibsen: A Dissenting View. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- Holtan, Orley (1990). Mythic Patterns in Ibsen's Last Plays. Minneapolis: U of Minneapolis P.

- Ibsen, Henrik (2017) [1891]. "Hedda Gabler". In Gainor, J. Ellen; Garner Jr., Stanton B.; Puchner, Martin. The Norton Anthology of Drama. Volume 2 (Third ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Jacobsen, Per Schelde (1988). Ibsen's Forsaken Merman: Folklore in the Later Plays. New York: NYU UP.

- Lavrin, Janko (1969) [1950]. Ibsen: An Approach. New York: Russell and Russell.

- Rhodes, Norman (1995). Ibsen and the Greeks: The Classical Greek Dimension in Selected Works of Henrik Ibsen as Mediated by German and Scandinavian Culture. Lewisburg: Bucknell UP.

- Robins, Elizabeth (1973) [1928]. Ibsen and the Actress. The Hogarth Essays, Second Series. New York: Haskell House.

- Salome, Lou (1985). Ibsen's Heroines. Austrian/German Culture Series. Translated by Mandel, Siegfried. Redding Ridge: Black Swan.

- Templeton, Joan (1997). Ibsen's Women. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- Young, Robin (1989). Time's Disinherited Children: Childhood, Regression, and Sacrifice in the Plays of Henrik Ibsen. Norwich: Norvik Press.