June 10, 2020: Difference between revisions

(Created page.) |

m (Added cat.) |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{cquote|The violence is the book. The Judge is the book, and the Judge is, short of ''Moby Dick'', the most monstrous apparition in all of American literature. The Judge is violence incarnate. The Judge stands for incessant warfare for its own sake.|author=Harold Bloom{{sfn|Pierce|2009|}} }} | {{cquote|The violence is the book. The Judge is the book, and the Judge is, short of ''Moby Dick'', the most monstrous apparition in all of American literature. The Judge is violence incarnate. The Judge stands for incessant warfare for its own sake.|author=Harold Bloom{{sfn|Pierce|2009|}} }} | ||

Maybe it’s that the whole narrative has a Biblical, epical, or fabalistic quality to it that removes it from the quotidian and mitigates its violence. David Vann calls it an “American Inferno,” likening McCarthy’s surrealistic landscapes with those of Dante: “Hell here is an open desert landscape, an endless journey past demonic shapes and beings living and dead.”{{sfn|Vann|2009|}} Indeed, since the kid is shot at the beginning of the novel, and this might be his own journey through hell,{{efn|Thanks to my friend Todd Hoffman for this idea when we were discussing the novel.}} except without the benefit of a Virgil—only accompanied and later pursued by the devil himself in the form of a seven-foot-tall, bald albino calling himself the Judge. | {{dc|S}}{{start|omething strikes me about [[w:Cormac McCarthy|Cormac McCarthy]]’s 1985 novel ''[[w:Blood Meridian|Blood Meridian]]''}} as more apposite today than when it was written. Maybe, as the interview points out, McCarthy was aware of a resurgence of the power of evangelical Christianity, but the mid-eighties seemed to me (what the hell did I know as a 16-year-old?) as a more placid time when compared to the fractious, post-fact world where God’s most devoted seem to be doing the devil’s work. This might be another way of saying: [[w:Judge Holden|the Judge]], while obviously a mythical antagonist, did not seem as horrific as I expected. | ||

[[File:Mccarthy-bm.jpeg|thumb|600px]] | |||

Maybe it’s that the whole narrative has a Biblical, epical, or fabalistic quality to it that removes it from the quotidian and mitigates its violence. David Vann calls it an “American Inferno,” likening McCarthy’s surrealistic landscapes with those of Dante: “Hell here is an open desert landscape, an endless journey past demonic shapes and beings living and dead.”{{sfn|Vann|2009|}}{{efn|I connected Dante and McCarthy in a [[February 9, 2012|paper I wrote on ''The Road'']] in 2012.}} Indeed, since the kid is shot at the beginning of the novel, and this might be his own journey through hell,{{efn|Thanks to my friend Todd Hoffman for this idea when we were discussing the novel.}} except without the benefit of a Virgil—only accompanied and later pursued by the devil himself in the form of a seven-foot-tall, bald albino calling himself the Judge. | |||

Virgil might be missing because this is virginal hell—one that has grown out of a new form of savageness in the American west. Dante’s ''La comedia'' is also a redemption story, but you’ll get nothing like that here. Is America newly damned in the mid-eighties, or has it always been so? The Judge is both Ahab ''and'' the white | Virgil might be missing because this is virginal hell—one that has grown out of a new form of savageness in the American west. Dante’s ''La comedia'' is also a redemption story, but you’ll get nothing like that here. Is America newly damned in the mid-eighties, or has it always been so? The Judge is both Ahab ''and'' the white whale{{efn|Maybe a Frankenstein’s monster or a Mephistopheles?}}—a monstrous baby [[w:Shiva|Shiva]] that dances the destruction of all he sees. His quest is unmaking: “In order for it to be mine nothing must be permitted to occur upon it save by my dispensation.” “It” here is creation, and the Judge delights in recording things in his notebook before destroying them,{{efn|There may be a connection here between the genuine and the copy through digital technology. Perhaps this is a link to Mailer’s devil in technology?}} as if the beauty in an object or idea can only be experienced though its destruction—its unmaking. The ultimate form of this is war. I can see the Judge, demon-like, dancing on the walls as Troy burns. The dance becomes his metaphor for never-ending war: the contest where the loser dies because he could not match the violence of his opponent. Near the end of the the novel, the Judge asks the man: “What man would not be a dancer if he could, said the judge. It’s a great thing, the dance.” The dance speaks to something primal in humanity that, at times, is allowed free reign. The Judge’s question speaks to the dancer buried deep within us all under morality and compassion and weakness. | ||

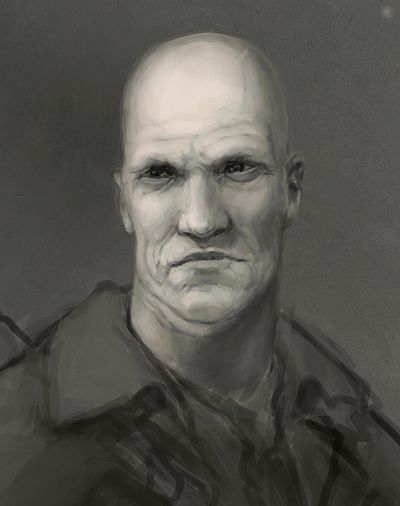

[[File:The-judge-blood-meridian.jpeg|thumb|left|400px]] | |||

The Judge is a contradiction in this sense: he is the most educated and refined of the characters and easily the most deprived.{{sfn|Hartman|2014|}} As Hartman points out “materialism and rationalism are not the antidotes to madness” or savagery as a humanistic tradition proposes. A mixture of the landscape, perhaps, and the Judge’s learning and intellect make him a kind of Nietzschean superman. At one point, he states: | |||

. . . | {{cquote|Moral law is an invention of mankind for the disenchantment of the powerful in favor of the weak. Historical law subverts it at every turn. A moral view can never be proven right or wrong by any ultimate test.}} | ||

Morality, then, becomes a rough veneer that covers up the truth of our existence: we are a violent race or creatures, and given the chance, this truth will rise to the surface. Interestingly, this suggests a kind of ethic in the Judge’s view: the we ultimately have a responsibility, then, to be the most violent that we can be to . . . what? To achieve our ultimate undoing? I can see why many think ''Blood Meridian'' espouses a frightening nihilism. | |||

{{* * *}} | |||

The kid is backgrounded in much of the novel—his story frames the action, as he is present at the beginning and the end. The center of the novel is about the inhumanity of the abstract [[w:John Joel Glanton|Glanton Gang]]: the scalp hunters that butcher their way west, murdering and scalping the violent natives as well as the peaceful ones. McCarthy does his best to show their worst. Glanton is a twisted psycho, but the Judge is some more heinous—leaving corpses of children he has abducted and raped in his tracks. At one point, he even buys two puppies from a Mexican boy and throws them off a bridge. In essence, these guys are the worst of the worst. (At one point the gang comes upon a “bush that was hung with dead babies,” and since there was no reaction or additional commentary, I got the impression that this was something the gang had done at some earlier point. It was their fault somehow. The novel is full of this kind of horrific surrealism.) | |||

This is why, I think, the center of the novel belongs to Glanton and the Judge. I assume that the kid (and Toadvine and the expriest) is taking part in these savage acts, but McCarthy never singles him out like he does Glanton and the Judge. The Glangton Gang—“they”—butcher and scalp, not “the kid.” Occasionally, too, the expriest and Toadvine react negatively to something the Judge does (Toadvine shoots the puppies that the Judge threw in the river, for example, rather than let them drown), but the kid has a passive almost ''non-presence'' in much of the book. | |||

This fact might allow us to connect with the kid as protagonist, but this is kind of a stretch. The narrator states early on: “He can neither read nor write and in him broods already a taste for mindless violence.” The rhetoric suggests that perhaps the “mindless violence” is a consequence of is illiteracy. Maybe McCarthy is teasing us here, as we have yet to meet the Judge. In light of the Judge, maybe it’s the kid’s ''lack'' of education that allows him to actually temper his “mindless violence”? | |||

{{* * *}} | |||

I’m thinking of a paper that compares ''BM'' with Mailer’s ''AAD''. Obviously, I need to do some research. ''BM'' has a way of getting under your skin. Is it too early to reread it? | |||

=== Notes === | === Notes === | ||

| Line 15: | Line 31: | ||

=== Citations === | === Citations === | ||

{{Reflist}} | {{Reflist|15em}} | ||

=== Works Cited === | === Works Cited === | ||

{{Refbegin|indent=yes}} | {{Refbegin|indent=yes|20em}} | ||

* {{cite web |url=https://s-usih.org/2014/01/blood-meridian-and-its-implications/ |title=''Blood Meridian'' and Its Implications |last=Hartman |first=Andrew |date=January 14, 2014 |website=Society for U.S. Intellectual History |publisher= |access-date=2020-06-13 |quote= |ref=harv }} | |||

* {{cite book |last=McCarthy |first=Cormac |date=2010 |orig-year=1985 |title=Blood Meridian or the Evening Redness in the West |url=https://amzn.to/2UIwja1 |location=New York |publisher=Vintage |version=Kindle |pages= |isbn= |author-link= |ref=harv }} | |||

* {{cite web |url=https://www.avclub.com/harold-bloom-on-blood-meridian-1798216782 |title=Harold Bloom on ''Blood Meridian'' |last=Pierce |first=Leonard |date=June 15, 2009 |website=AV Club |publisher= |access-date=2020-06-11 |quote= |ref=harv }} | * {{cite web |url=https://www.avclub.com/harold-bloom-on-blood-meridian-1798216782 |title=Harold Bloom on ''Blood Meridian'' |last=Pierce |first=Leonard |date=June 15, 2009 |website=AV Club |publisher= |access-date=2020-06-11 |quote= |ref=harv }} | ||

* {{cite web |url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2009/nov/14/david-vann-cormac-mccarthy |title=American Inferno |last=Vann |first=David |date=November 13, 2009 |website=The Guardian |publisher= |access-date=2020-06-11 |quote= |ref=harv }} | * {{cite web |url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2009/nov/14/david-vann-cormac-mccarthy |title=American Inferno |last=Vann |first=David |date=November 13, 2009 |website=The Guardian |publisher= |access-date=2020-06-11 |quote= |ref=harv }} | ||

| Line 26: | Line 44: | ||

[[Category:06/2020]] | [[Category:06/2020]] | ||

[[Category:Books]] | [[Category:Books]] | ||

[[Category:Cormac McCarthy]] | |||

Latest revision as of 07:35, 19 July 2022

Finished Blood Meridian covid-19: day 89 | US: GA | info | act

| “ | The violence is the book. The Judge is the book, and the Judge is, short of Moby Dick, the most monstrous apparition in all of American literature. The Judge is violence incarnate. The Judge stands for incessant warfare for its own sake. | ” |

| — Harold Bloom[1] | ||

Something strikes me about Cormac McCarthy’s 1985 novel Blood Meridian as more apposite today than when it was written. Maybe, as the interview points out, McCarthy was aware of a resurgence of the power of evangelical Christianity, but the mid-eighties seemed to me (what the hell did I know as a 16-year-old?) as a more placid time when compared to the fractious, post-fact world where God’s most devoted seem to be doing the devil’s work. This might be another way of saying: the Judge, while obviously a mythical antagonist, did not seem as horrific as I expected.

Maybe it’s that the whole narrative has a Biblical, epical, or fabalistic quality to it that removes it from the quotidian and mitigates its violence. David Vann calls it an “American Inferno,” likening McCarthy’s surrealistic landscapes with those of Dante: “Hell here is an open desert landscape, an endless journey past demonic shapes and beings living and dead.”[2][a] Indeed, since the kid is shot at the beginning of the novel, and this might be his own journey through hell,[b] except without the benefit of a Virgil—only accompanied and later pursued by the devil himself in the form of a seven-foot-tall, bald albino calling himself the Judge.

Virgil might be missing because this is virginal hell—one that has grown out of a new form of savageness in the American west. Dante’s La comedia is also a redemption story, but you’ll get nothing like that here. Is America newly damned in the mid-eighties, or has it always been so? The Judge is both Ahab and the white whale[c]—a monstrous baby Shiva that dances the destruction of all he sees. His quest is unmaking: “In order for it to be mine nothing must be permitted to occur upon it save by my dispensation.” “It” here is creation, and the Judge delights in recording things in his notebook before destroying them,[d] as if the beauty in an object or idea can only be experienced though its destruction—its unmaking. The ultimate form of this is war. I can see the Judge, demon-like, dancing on the walls as Troy burns. The dance becomes his metaphor for never-ending war: the contest where the loser dies because he could not match the violence of his opponent. Near the end of the the novel, the Judge asks the man: “What man would not be a dancer if he could, said the judge. It’s a great thing, the dance.” The dance speaks to something primal in humanity that, at times, is allowed free reign. The Judge’s question speaks to the dancer buried deep within us all under morality and compassion and weakness.

The Judge is a contradiction in this sense: he is the most educated and refined of the characters and easily the most deprived.[3] As Hartman points out “materialism and rationalism are not the antidotes to madness” or savagery as a humanistic tradition proposes. A mixture of the landscape, perhaps, and the Judge’s learning and intellect make him a kind of Nietzschean superman. At one point, he states:

| “ | Moral law is an invention of mankind for the disenchantment of the powerful in favor of the weak. Historical law subverts it at every turn. A moral view can never be proven right or wrong by any ultimate test. | ” |

Morality, then, becomes a rough veneer that covers up the truth of our existence: we are a violent race or creatures, and given the chance, this truth will rise to the surface. Interestingly, this suggests a kind of ethic in the Judge’s view: the we ultimately have a responsibility, then, to be the most violent that we can be to . . . what? To achieve our ultimate undoing? I can see why many think Blood Meridian espouses a frightening nihilism.

The kid is backgrounded in much of the novel—his story frames the action, as he is present at the beginning and the end. The center of the novel is about the inhumanity of the abstract Glanton Gang: the scalp hunters that butcher their way west, murdering and scalping the violent natives as well as the peaceful ones. McCarthy does his best to show their worst. Glanton is a twisted psycho, but the Judge is some more heinous—leaving corpses of children he has abducted and raped in his tracks. At one point, he even buys two puppies from a Mexican boy and throws them off a bridge. In essence, these guys are the worst of the worst. (At one point the gang comes upon a “bush that was hung with dead babies,” and since there was no reaction or additional commentary, I got the impression that this was something the gang had done at some earlier point. It was their fault somehow. The novel is full of this kind of horrific surrealism.)

This is why, I think, the center of the novel belongs to Glanton and the Judge. I assume that the kid (and Toadvine and the expriest) is taking part in these savage acts, but McCarthy never singles him out like he does Glanton and the Judge. The Glangton Gang—“they”—butcher and scalp, not “the kid.” Occasionally, too, the expriest and Toadvine react negatively to something the Judge does (Toadvine shoots the puppies that the Judge threw in the river, for example, rather than let them drown), but the kid has a passive almost non-presence in much of the book.

This fact might allow us to connect with the kid as protagonist, but this is kind of a stretch. The narrator states early on: “He can neither read nor write and in him broods already a taste for mindless violence.” The rhetoric suggests that perhaps the “mindless violence” is a consequence of is illiteracy. Maybe McCarthy is teasing us here, as we have yet to meet the Judge. In light of the Judge, maybe it’s the kid’s lack of education that allows him to actually temper his “mindless violence”?

I’m thinking of a paper that compares BM with Mailer’s AAD. Obviously, I need to do some research. BM has a way of getting under your skin. Is it too early to reread it?

Notes

- ↑ I connected Dante and McCarthy in a paper I wrote on The Road in 2012.

- ↑ Thanks to my friend Todd Hoffman for this idea when we were discussing the novel.

- ↑ Maybe a Frankenstein’s monster or a Mephistopheles?

- ↑ There may be a connection here between the genuine and the copy through digital technology. Perhaps this is a link to Mailer’s devil in technology?

Citations

Works Cited

- Hartman, Andrew (January 14, 2014). "Blood Meridian and Its Implications". Society for U.S. Intellectual History. Retrieved 2020-06-13.

- McCarthy, Cormac (2010) [1985]. Blood Meridian or the Evening Redness in the West. Kindle. New York: Vintage.

- Pierce, Leonard (June 15, 2009). "Harold Bloom on Blood Meridian". AV Club. Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- Vann, David (November 13, 2009). "American Inferno". The Guardian. Retrieved 2020-06-11.