August 2, 2021: Difference between revisions

m (Updated cat.) |

(Added background.) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Journal-Top}}<div style="padding-top: 30px;"> | {{Journal-Top}} __NOTOC__ <div style="padding-top: 30px;"> | ||

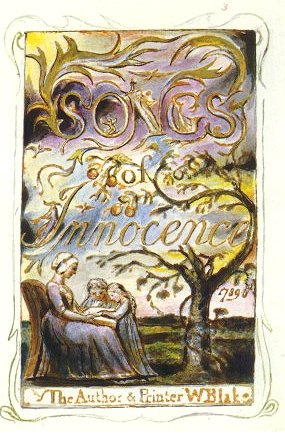

[[File:Blake Innocence Title.jpg|thumb]] | [[File:Blake Innocence Title.jpg|thumb]] | ||

{{Center|{{Large|Introduction}}{{refn|The introductory poem from the ''[[w:Songs of Innocence and of Experience#Songs of Innocence|Songs of Innocence]]'', 1789, which defines the “emotional conditions” of the poems in this book {{harvnb|Tomlinson|1987|p=27}}). However, these are not poems that reflect an innocence in ''reality'' as many of them contain images of suffering and injustice, but instead show the emotional state of the, in Blake’s words, “human soul” that views them ({{harvnb|Greenblatt|2018|p=48}}). Much of Blake’s poetry is polyvocal in that he does not present one, unified voice, but shows many different “dramatisations of various mental states and attitudes” ({{harvnb|Ackroyd|1995|p=141}}).<br />{{sp}}Compare this poem to its ''contraries'', the “[[Introduction (SE)|Introduction]]” and “[[Earth’s Answer]]” from ''Songs of Experience''. See also the introductory note on “[[The Lamb]]” for more background into Blake’s poetic composition and philosophy.}}<br /> | {{Center|{{Large|Introduction}}{{refn|The introductory poem from the ''[[w:Songs of Innocence and of Experience#Songs of Innocence|Songs of Innocence]]'', 1789, which defines the “emotional conditions” of the poems in this book {{harvnb|Tomlinson|1987|p=27}}). However, these are not poems that reflect an innocence in ''reality'' as many of them contain images of suffering and injustice, but instead show the emotional state of the, in Blake’s words, “human soul” that views them ({{harvnb|Greenblatt|2018|p=48}}). Much of Blake’s poetry is polyvocal in that he does not present one, unified voice, but shows many different “dramatisations of various mental states and attitudes” ({{harvnb|Ackroyd|1995|p=141}}).<br />{{sp}}Compare this poem to its ''contraries'', the “[[Introduction (SE)|Introduction]]” and “[[Earth’s Answer]]” from ''Songs of Experience''. See also the introductory note on “[[The Lamb]]” for more background into Blake’s poetic composition and philosophy.}}<br /> | ||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

|}</div> | |}</div> | ||

====Notes | ===Background=== | ||

William Blake's “Introduction” to his ''Songs of Innocence'', first published in 1789, serves as a prelude to the themes and stylistic features of the entire collection. Blake, a visionary poet and artist, was deeply influenced by his spiritual beliefs, social concerns, and a desire to capture the purity and simplicity of the childlike perspective. This introductory poem sets the tone for the ''Songs of Innocence'' by presenting an idealized view of childhood and the natural world, central motifs in Romantic literature. | |||

The poem employs a simple yet structured form, consisting of five quatrains with an ABAB rhyme scheme, which reflects the straightforward and musical quality of a song or nursery rhyme. The first stanza introduces a piper who is joyously piping songs. This image of the piper and the child establishes the pastoral and innocent atmosphere that characterizes the collection. The interaction between the piper and the child symbolizes the transmission of inspiration and creativity, themes that are central to Blake’s poetic vision. | |||

The child, a recurring figure in Blake’s work, represents innocence and purity. In the second stanza, the child instructs the piper to “Pipe a song about a Lamb,” which introduces the motif of the lamb as a symbol of innocence and gentleness. The lamb, a traditional Christian symbol, aligns with Blake’s spiritual influences and his emphasis on themes of innocence and divine creation. | |||

As the poem progresses, the child requests that the piper sing the songs and then write them down, thus transforming the oral tradition into written form. This transition reflects Blake’s own process of creating illuminated books, combining text and illustration to convey his visions. The act of writing with a “hollow reed” suggests a natural and humble approach to artistic creation, in keeping with the themes of simplicity and innocence. | |||

Additional themes include the celebration of innocence, the power of the imagination, and the role of the artist as a mediator between divine inspiration and human experience. The poem embodies Romantic characteristics such as a focus on nature, emotion, and the childlike perspective, which Blake and his contemporaries saw as closer to spiritual truth. | |||

Contemporary relevance lies in its exploration of the creative process and the value of preserving innocence in a complex and often corrupt world. The poem’s emphasis on simplicity, joy, and the purity of childhood continues to resonate, offering a critique of modernity’s loss of these qualities. In an era increasingly dominated by technology and materialism, Blake’s vision of returning to a state of innocence and creative freedom remains poignant and thought-provoking. | |||

===Notes=== | |||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

Revision as of 08:33, 17 August 2024

|

Piping down the valleys wild |

Background

William Blake's “Introduction” to his Songs of Innocence, first published in 1789, serves as a prelude to the themes and stylistic features of the entire collection. Blake, a visionary poet and artist, was deeply influenced by his spiritual beliefs, social concerns, and a desire to capture the purity and simplicity of the childlike perspective. This introductory poem sets the tone for the Songs of Innocence by presenting an idealized view of childhood and the natural world, central motifs in Romantic literature.

The poem employs a simple yet structured form, consisting of five quatrains with an ABAB rhyme scheme, which reflects the straightforward and musical quality of a song or nursery rhyme. The first stanza introduces a piper who is joyously piping songs. This image of the piper and the child establishes the pastoral and innocent atmosphere that characterizes the collection. The interaction between the piper and the child symbolizes the transmission of inspiration and creativity, themes that are central to Blake’s poetic vision.

The child, a recurring figure in Blake’s work, represents innocence and purity. In the second stanza, the child instructs the piper to “Pipe a song about a Lamb,” which introduces the motif of the lamb as a symbol of innocence and gentleness. The lamb, a traditional Christian symbol, aligns with Blake’s spiritual influences and his emphasis on themes of innocence and divine creation.

As the poem progresses, the child requests that the piper sing the songs and then write them down, thus transforming the oral tradition into written form. This transition reflects Blake’s own process of creating illuminated books, combining text and illustration to convey his visions. The act of writing with a “hollow reed” suggests a natural and humble approach to artistic creation, in keeping with the themes of simplicity and innocence.

Additional themes include the celebration of innocence, the power of the imagination, and the role of the artist as a mediator between divine inspiration and human experience. The poem embodies Romantic characteristics such as a focus on nature, emotion, and the childlike perspective, which Blake and his contemporaries saw as closer to spiritual truth.

Contemporary relevance lies in its exploration of the creative process and the value of preserving innocence in a complex and often corrupt world. The poem’s emphasis on simplicity, joy, and the purity of childhood continues to resonate, offering a critique of modernity’s loss of these qualities. In an era increasingly dominated by technology and materialism, Blake’s vision of returning to a state of innocence and creative freedom remains poignant and thought-provoking.

Notes

- ↑ The introductory poem from the Songs of Innocence, 1789, which defines the “emotional conditions” of the poems in this book Tomlinson 1987, p. 27). However, these are not poems that reflect an innocence in reality as many of them contain images of suffering and injustice, but instead show the emotional state of the, in Blake’s words, “human soul” that views them (Greenblatt 2018, p. 48). Much of Blake’s poetry is polyvocal in that he does not present one, unified voice, but shows many different “dramatisations of various mental states and attitudes” (Ackroyd 1995, p. 141).

Compare this poem to its contraries, the “Introduction” and “Earth’s Answer” from Songs of Experience. See also the introductory note on “The Lamb” for more background into Blake’s poetic composition and philosophy. - ↑ The narrator is the piper, a child in tune with nature, suggesting a more emotional, rather than intellectual or ration, connection with the world that is reflected in the content of the poem.

- ↑ The child, a personification of innocence and a care-free existence, asks the piper to to write down his songs to share with the world, and perhaps preserve them as remembrances of more innocent times for when he grows up Tomlinson 1987, p. 27). Indeed, the child disappears at the moment the piper begins to write, suggesting that the process of composition leads to wisdom in some way—compare to the Bard in this poem’s contrary, who “Who Present, Past, & Future sees.” The child may have been some aspect of the piper, an allegory of the waning innocence of the piper, perhaps. The purpose of these songs might be to spark joy, but also to remind us of what a lost innocence is like.

- ↑ Again, the act of writing stains the purity of the moment, passing it through the imagination and the pen of the poet. Perhaps there must be experience before the imagination may reflect on the state of innocence.

Bibliography

- Ackroyd, Peter (1995). Blake: A Biography. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Battenhouse, Henry M. (1958). English Romantic Writers. New York: Barron’s Educational Series, Inc.

- Bloom, Harold (2003). William Blake. Bloom’s Major Poets. New York: Chelsea House.

- Frye, Northrup (1947). Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Gardner, Stanley (1969). Blake. Literary Critiques. New York: Arco.

- Green, Martin Burgess (1972). Cities of Light and Sons of Morning. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Greenblatt, Stephen, ed. (2018). The Norton Anthology of English Literature. The Major Authors. 2 (Tenth ed.). New York: W. W. Norton.

- Makdisi, Saree (2003). "The Political Aesthetic of Blake's Images". In Eaves, Morris. The Cambridge Companion to William Blake. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP. pp. 110–132.

- — (2015). Reading William Blake. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Paulin, Tom (March 3, 2007). "The Invisible Worm". Guardian. Retrieved 2021-09-04.

- Thompson, E. P. (1993). Witness Against the Beast. New York: The New Press.

- Tomlinson, Alan (1987). Song of Innocence and of Experience by William Blake. MacMillan Master Guides. London: MacMillan Education.

- Wolfson, Susan J. (2003). "Blake's Language in Poetic Form". In Eaves, Morris. The Cambridge Companion to William Blake. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP. pp. 63–83.

Links and Web Resources

- Blake at the Internet Archive.

- Blake’s Notebook at the British Museum.

- William Blake Study Questions