Religion Good for Something?

I finished Butler’s Parable of the Talents today, and it was even better than Parable of the Sower—which is quite a feat. I think with the additional voices Butler included, particularly that of Olamina’s daughter, Butler was able to nuance her protagonist and show the flawed side of being a revolutionary, or what Asha Vere would call a cult leader. The two aspects of the book that I had the most difficulty with where (1) the concept of the sharers, and (2) the Earthseed Destiny.

Olamina is a sharer—i.e., she is a hyper-empath who felt the obvious pain/pleasure of people she looked at—mostly the former. This defect—Olamina sees it as such—is the result of her mother’s addiction to a certain drug. Olamina sees her sharing as a defect because it makes her easy to control or incapacitate in an unpredictable or violent world. I guess my problem with it was Butler never seemed to make this an integral part of the novels. It was just something about Olamina and a few others that occasionally popped up. I even forgot about it occasionally until I was reminded. While I’m still unsure as to why this trait was included, it might have something to do with the way the novel develops the idea of true religion.

While Talents shows the negative capacity of religion in the authoritarian Christian America movement, she also uses it as a guiding force that allows humanity to literally reach for the stars. Olamina calls it “a guiding force, that can help humanity to put it’s great energy, competitiveness, and creativity to work doing the truly vast job of fulfilling the Destiny.”[1] No corporation and no government can supply the, let’s say spirit, needed to guide what could be the generations needed to guide humanity to ultimately leave the nest. In fact, in Sower, America’s space program was scrapped by the incoming president as a waste of resources when so many problems exist at home. This sounds familiar: corporations and politicians with their myopic vision only seeing what’s right in front of them. This will keep us forever infantialized and condemn us to die on without ever leaving home.

It’s too bad that religion always turns into something negative—something that seeks to utter the only truth while becoming an authoritarian force that seeks to obliterate questions or dissent. Butler’s Earthseed was not like this, but I wonder how long it would stay a positive force without adopting the fascism that every other religion seems to pick up—yes even Buddhism.

Another idea in the novel, also related to religion—particularly the Christian America movement—was the taking away of Earthseed’s children from Acorn. Like in The Handmaid’s Tale, Talents has an oppressive religious force ripping children away from their biological parents and their birth communities, essentially robbing these people of their futures. They are given to families who will raise them “right”: with the morals and practices of Christian America and Gilead. Ultimately, Talents shows that while this causes pain to Olamina and her community, it does not stop them from fulfilling their destiny: we, humans, are a family, after all.

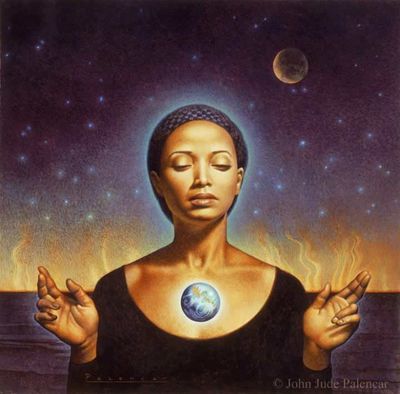

I think this why it was important for Olamina to be a sharer: true religion requires empathy to be a positive for for all of humanity. Too much we see religion attempting to impose its ideas and dominate through the word of God that it can’t see the damage that it does to others and also its own adherents. Often religion would ask believers to kill and die for an idea; Butler proposes a religion that would seek to have us grow and live. It’s message is sanguine and difficult for me to see in the darkness that our world seems to be falling into. Yet, Butler’s novels paint dark and grim versions of our near future, but there is light on the other side. I wonder.

note

- ↑ Butler, Octavia E. (1998). Parable of the Talents. Kindle. Open Road Media Sci-Fi & Fantasy. p. 6096.