Driving Salman Rushdie

I didn’t know what to expect. I had been nervous for the last two days, as if I were the one entering the spotlight. Unassuming and cordial if a bit frazzled from rising early to catch a flight from Austin, Salman Rushdie smiled as he shook my hand. As Phil was driving, Salman rode shotgun, and I sat behind the author of some of the words that have shaped my intellectual development since I discovered the study of literature over a decade ago.

Rushdie has always made literature real for me, like significant life experiences that leave a mark in the brain as they sometimes do on the body. His work challenges the quotidian by eloquently presenting the middle finger to tradition and conventional wisdom, a defiance that proves admirable and frequently necessary, but crossed the line at a time when the ruling right in Iran decided that some stories and beliefs are too sacred to be challenged, so they sentenced Rushdie to death for telling his story at the expense of the holy. While Khomenei’s very real threat lasted over a decade, Rushdie still writes while the decreer of the infamous fatwa lies cold in the ground. There’s nothing like the threat of bodily harm to humble one’s convictions and determination, but Rushdie’s work still maintains an irony that scrutinizes the very stories that define much of the human condition.

During the two days I spent with Rushdie—through his three presentations, two meals, and several drives across Tampa Bay—we managed to discuss aspects of his work, music, politics, others’s works, and my own concerns about teaching and living in this world. At first, I was self-conscious in addressing the man that has been so significant to my own development, but Salman (he suggested I call him that) was gracious and thoughtful, answering my questions and presenting his own in an equitable exchange of ideas. Our conversations, while brief, were dynamic and smart, at least as much the few opportunities allowed. Rushdie’s knowledge spanned the disciplines, right into popular culture: he could talk about anything, and did. I tried to listen as much as I could, only interjecting when I felt I really had something to add, or a question to pose. What I discovered, much to my delight, is that he and I share many positions about culture and the world. A discussion about the Coen brothers presents a memorable example: we both admire the bulk of their films, but we both share a similar opinion about Miller’s Crossing and The Big Lebowski. I had always considered the former to be too ponderous, lacking the pacing and the humor of their other works, with the exception of Blood Simple. He agreed, finding the movie one of the more difficult of their works. In addition, he feels Lebowski is a delightful film that didn’t get the attention or critical reception that it deserved. Again, I have always held a similar opinion, but have remained in a minority.

I don’t make this observation to prove my brilliance, but only to suggest how easy it was to talk with Rushdie and to illustrate an affinity that I felt with him during our brief time. At one point during our discussion on the way to his second speaking engagement in Tampa, I brought up a marginal character in The Satanic Verses: the only American character in that novel that I can recall. This character is a loud-mouthed know-it-all who is part of a group of hostages on a plane with the novel’s protagonists. This American’s (I can’t remember the name, but I think he was from Texas) insistance and overbearing demeanor eventually provoke one of the terrorists into taking action with a rifle butt to this guy’s jaw. The American loses part of his tongue from the blow and later has it replaced with flesh from his ass. The image remained with me since, suggesting a little satirical jab toward many Americans. I forget the context of our conversation, but Rushdie chuckled at my mention of this character and not much more was said about it. Later at his speech in front of about 400 people, he brought up our conversation saying that “someone unfairly” suggested that this character was the only American in the novel. Perhaps I imagined it, but I could swear he was looking at me when the audience laughed.

His discussions were simply delightful. He is a confident, articulate speaker who practices what he advocates in his works. He was outspoken against organized religion, criticizing its potentially negative effects on free thought and imagination. His opinion was potentially offensive to many of the conservative administrators and academics in the room, but he said it with apparent impunity and a lack of any arrogance. This audience also did not keep him from responding to a question about Eldred vs. Ashcroft in a pithy and vulgar fashion: “Well, you don’t fuck with the mouse.” Politically inappropriate? Perhaps, but he is Salman Rushdie, survivor of the fatwa, and it’s his creative scrutiny—or [[Healthy Blasphemy|healthy blasphemy]—that I admire the most. When I dropped him off at the airport about an hour ago, he signed my first-edition of Verses: “To Jerry with thanks, Salman Rushdie.”

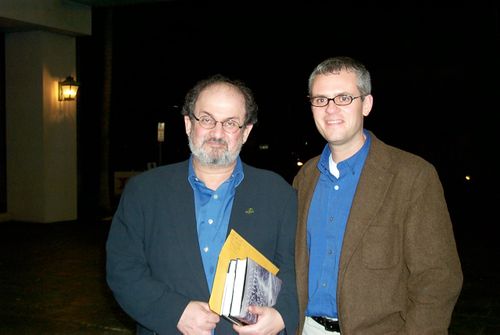

In all, an unforgettable couple of days. I want to thank Phil for making it all possible and giving me a place to stay. Also, thanks to Betty, Steve, and Legretta for letting me play a role in this event. I’ll probably have more to say, but I wanted to get some initial impressions down. Here are the pictures that I was able to manage. Oh, buy his new book Step Across This Line.

And one final thing: he’s a Mac user. Talk about affinity!