April 5, 2013

Into Darkness

Norman Mailer’s portrayal of Gary Gilmore in The Executioner’s Song complicates and nuances Gilmore’s life and shows he is more than just a cold-hearted executioner.

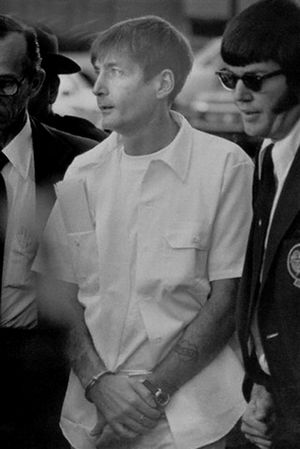

“Who cares about Gary Gilmore?” One of my students asked most incredulously during our discussion of Mailer’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning The Executioner’s Song. My wife would have a similar reaction during our viewing of the film later in the week. Indeed, I had to admit, Gilmore is not a very likable character, but neither are any of Mailer’s other protagonists, yet they generally don’t inspire this kind of emotional reaction.

Mailer is forever teasing his audience. He invites us into his world, one that takes its grit and beauty from the everyday, but filters it through the mind of the Novelist. The story we get, then, is less real, but perhaps more true. I frequently ask my students: is it facts that interest us, or the stories behind them? For Mailer the Novelist, casting light on facts is part of the story, but perhaps they are less important than the shadows that lie behind them.

Norman Mailer’s portrayal of Gary Gilmore in his 1979 novel-history-biography The Executioner’s Song is as complex and contradictory as one might expect in 1100 pages. Mailer’s narrative complicates and nuances Gilmore’s life — it shows that he is more than just the cold-hearted executioner the facts suggest. Judgment of Gilmore cannot be cast so easily. Mailer’s Gilmore is not evil, though he may be “further from God than [he is] from the devil.”[1] ES’ style is far from didactic and might be the most objective that the novelist could muster — almost the complete opposite of his other Pulitzer-prize winner The Armies of the Night. Interestingly, it’s Armies that won the Pulitzer for non-fiction, while ES took it for fiction. Here’s Mailer at his finest: presenting the story and letting us figure out the truth of it.

In his biography Norman Mailer: A Double Life, J. Michael Lennon writes that Mailer saw Gilmore as “a man who was quintessentially American and yet worthy of Dostoyevsky.”[2] Less a Raskonikov and more of an Underground Man, perhaps; definitely a product of an institutional America. Maybe Mailer saw some Svidrigailov, Smerdyakov, or Ivan Karamazov in him? Wait, perhaps the lusty Dmitri Karamazov fits best — the character ostensibly capable of murder to possess Grushenka. Unlike Svidrigailov and Smerdyakov — the true villains of CP and BK, respectively — Gilmore’s acts are not Machiavellian, but contain a passion that might be more akin to Dmitri’s dropping Katerina to chase Grushenka to Poland. Dmitiri is violent and impetuous, not cunning and evil like his bastard half-brother Smerdyakov. Gilmore describes himself in a similar way: “I’m impulsive. I don’t think.”[3]

However, like Smerdyakov, Gilmore is the product a system that disenfranchised and abused him — both societal and familial — compounding the likelihood or perhaps the inevitability of his becoming a murderer. Gilmore and Smerdyakov also have a hand in their own deaths. In addition to several suicide attempts throughout his life, Gilmore refuses to appeal his death sentence and fights voraciously to end his own life: a suicide by Utah firing squad. Throughout the novel, Gilmore admits to wrongdoing, and he accepts the sentence of the people. Perhaps it’s this act that makes him human ultimately, and allows us to feel compassion, even if we can’t condone his actions. Similarly, Smerdyakov takes his own life. In his suicide note, he writes: “I exterminate my life by my own will and liking, so as not to blame anybody.”[4] Taking his own life, ironically, humanizes Smerdyakov.

Do we get this? It is possible to read ES and not see Gilmore as a human being, I guess — and the same could be said for Smerdyakov in BK. If we don’t have a connection with Gilmore at the end of the novel, is that the fault of Mailer, or does it lie somewhere inside ourselves? It reminds me of Euripides’ Medea. If we finish the play thinking that Medea’s actions were the result of her insanity, then we miss the significance of it. Instead of tragedy, it becomes horror. Think of Oedipus’ words when the chorus asks: “What superhuman power drove you on?” He answers:

| “ | Apollo, friends, Apollo— |

” |

Why we suffer is beyond our control; how we handle it is the measure of our character. Like Oedipus, Medea, and Gilmore, we might not handle it in the best ways, but does that condemn us to the outer darkness?

I understand that Gilmore is no Oedipus, but perhaps Mailer’s characterization of Gilmore elevates him. Like tragedy, it removes us from the immediacy and spectacle that surrounded the case Gilmore the Murderer. The novel forces us to distance ourselves in order reconsider the emotions in a moment (or many moments) of tranquility. This is the truth of art. This is where Mailer takes us, acting as the Virgil to our Dante.

Gilmore’s story is full of darkness and demons, but there is a light in him that all who were close to him were illumined by. In his last meeting with his brother Mikal, Gary leaves him with a kiss on the mouth (à la Ivan’s Grand Inquisitor) and the words: “See you in the darkness” (866). These final words are ambiguous and perhaps a bit sinister. Does he mean this spiritually as in the Mormon outer darkness, or his own haunting in the troubled Mikal’s memory — a darkness that all Gilmore’s close friends and family will also share after his death? Interestingly, the novel ends with Gary and Mikal’s mother, Bessie. She sits, knees destroyed by arthritis, and defiantly awaits death — a death that she expects because of Gary’s demons — perhaps as penance for not doing more to help him. Despite the demons, she, like Gary, stands strong at the end.

Citations

- ↑ Mailer 1979, p. 305.

- ↑ Lennon 2013, p. 505.

- ↑ Mailer 1979, p. 800.

- ↑ Dostoyevsky 1992, p. 651.

Works Cited

- Dostoyevsky, Fyodor (1992). The Brothers Karamazov. Translated by Pevear, Richard; Volokhonsky, Larissa. New York: Everyman’s Library.

- Lennon, J. Michael (2013). Norman Mailer: A Double Life. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Mailer, Norman (1979). The Executioner's Song. Boston: Little, Brown.