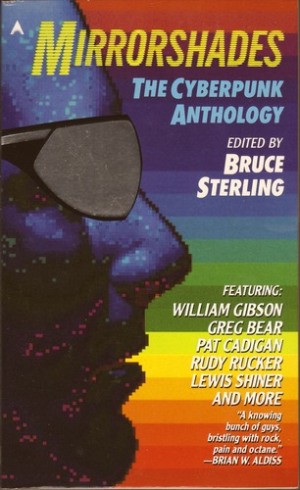

Mirrorshades, Part 1

I chose several stories from Sterling’s Mirrorshades this week for my Cyberpunk class, including Greg Bear’s “Petra,” Rudy Rucker’s “Tales of Houdini,” Paul di Filippo’s “Stone Lives,” Pat Cadigan’s “Rock On,” Lewis Shiner’s “Till Human Voices Wake Us,” and James Patrick Kelly’s “Solstice.” Quite a selection of great representative pieces. It’s our duty to synthesize some of their cyberpunk concerns.

At first, it might seem an impossible task to pick out intertextual themes, or even why Sterling chose to include some of these experimental stories in a cyberpunk anthology. Yet, while I’m sure there are others, these concerns seem to span this selection:

- Freedom comes at a high price, if at all.

- Lasting connection seems impossible or improbably in a high-tech world of distraction.

- Sex is strictly for entertainment, while procreation is a serious matter. Progeny is too important to be left up to chance.

- Reality is indistinguishable from technological mediation, especially when the latter rewrites the former so easily. The body should be upgraded and augmented.

- Ubiquitous technology transforms humans and their environments. It also alters perception.

- What used to be dead is now alive, and vice versa. Stone, rock, and flesh are equally malleable.

A thorough examination of each of these ideas within each story cannot be covered even cursorily here. However, perhaps addressing the body as area of struggle between meatspace and headspace might touch on them all. The body as the locus of struggle between external forces and internal desires is often a dominant theme in cyberpunk. As technology gets better at controlling - or manipulating - the meat, the head cannot be far behind. This is a double-edged sword: the forces on the outside seeking hegemony have more of a weapon for achieving it, just at the same time, freedom seems to be closer at hand.

“Stone Lives”

In “Stone Lives,” Paul di Filippo considers procreation, social responsibility, human augmentation, and corporate wealth in a coming-of-age tale. I’ll try to write about this story without ruining the end. Stone is literally given new eyes as he’s plucked out of the Bugle and given a job working for one of the most powerful women in the world. His enhanced vision - a gift from his benefactor Alice Citrine - allows him to see the civilized world as no other does, as does his bestial upbringing in the Bungle. Stone is cautious of this gift, thinking that it makes him a thrall to the desires of the corporation. Ironically, Stone realizes that his animalistic life in the Bungle was not much different from the “civilized world” he now calls home. Stone’s freedom is ultimately at stake.

Sex is strictly for entertainment, while procreation is a serious matter.

Di Filippo’s title is a contradiction, for stone, as we know it, cannot live. However, under the hands of an artist, stone can be shaped into something beautiful and deadly. Stone the protagonist was right to be wary, but it ultimately does him no good. The word “lives” is also a contrast to the theme of survival in the story. In the Bungle, Stone states that survival is key. Indeed, in the jungle, survival is life. However, civilization and progress should add to our estimation of life: isn’t this what technology is supposed to be for? Di Filippo leaves us wondering if indeed, Stone lives at all. Stone does, however, live up to his name.

Stone does have his moments of connection with Jane, but ultimately they are to prove a distraction. She, like Stone, has been made to serve the agenda of higher powers. Yet, unlike Stone, she is expendable, just like notions of romantic love. She does, however, play the role of the cyberpunk heroine: a reality instructor of sorts, who helps Stone through crucial moments in his education. In some respects, she is both lover and mother, another nod to cyberpunk’s recurring theme of dubious parentage.

“Solstice”

James Patrick Kelly’s “Solstice” is a haunting story: where the protagonist’s longing for a romantic world that he makes backfires because of his own myopia. Tony Cage is a drug artist and addict. He creates his own hallucinations, and he is very good at it. Not only that, he grows his Wynne from his own cells: “He refused to think of her as his daughter. Nor was she exactly his clone. She was like a twin [. . .] She was something new, something infinitely precious” (72). This is not all she turns out to be, but as the story goes on, she becomes symbolic of Cage’s, well, cage. She is his prize, something that he’ll do anything to protect, even if it means hurting others.

Wynne is wrapped up with Cage’s fascination for Stonehenge: the mysterious circle of stones (stone again!) that defy explanation. Kelly intersperses historical explanations of Stonehenge throughout “Solstice,” and scenes at the monument also bracket the story. Stonehenge’s mystery and subsequent mysticism seem to link it thematically with drugs and altered perception. The Stonehenge digressions are about explaining it in a rational way - all of which fall short. Even the observation that the rising sun of the solstice aligns with it perfectly is not true. To be experienced in a meaningful way, the “surround” of Stonehenge must be mediated. (Indeed, visiting the actual Stonehenge cannot live up to the hype of a mediated one. Which, then, becomes more real? I state this through experience. I shot many photos of Stonehenge, both objective and augmented. Which represents it in a truer way?) Drugs in “Solstice,” might also represent media in general, and computers specifically.

Cage is a great cyberpunk hero: he is the hacker supreme, living in his own headspace. He wants to change his meatspace to match his vision. Perhaps he is a Pygmalion figure, and Wynne is his ivory statue come to life: his Galatea. Cage, in his desire to create his own perfect world with Wynne at the center, becomes blind to her needs and desires as an autonomous human being and tries to imprison her, too. Yet, no matter how beautiful the cage, it is still a cage. Tony, to his credit, does realize this at the end, only after he almost ends her life. He grants her freedom (was it his to give her?), but draws further back into himself. A bittersweet end.