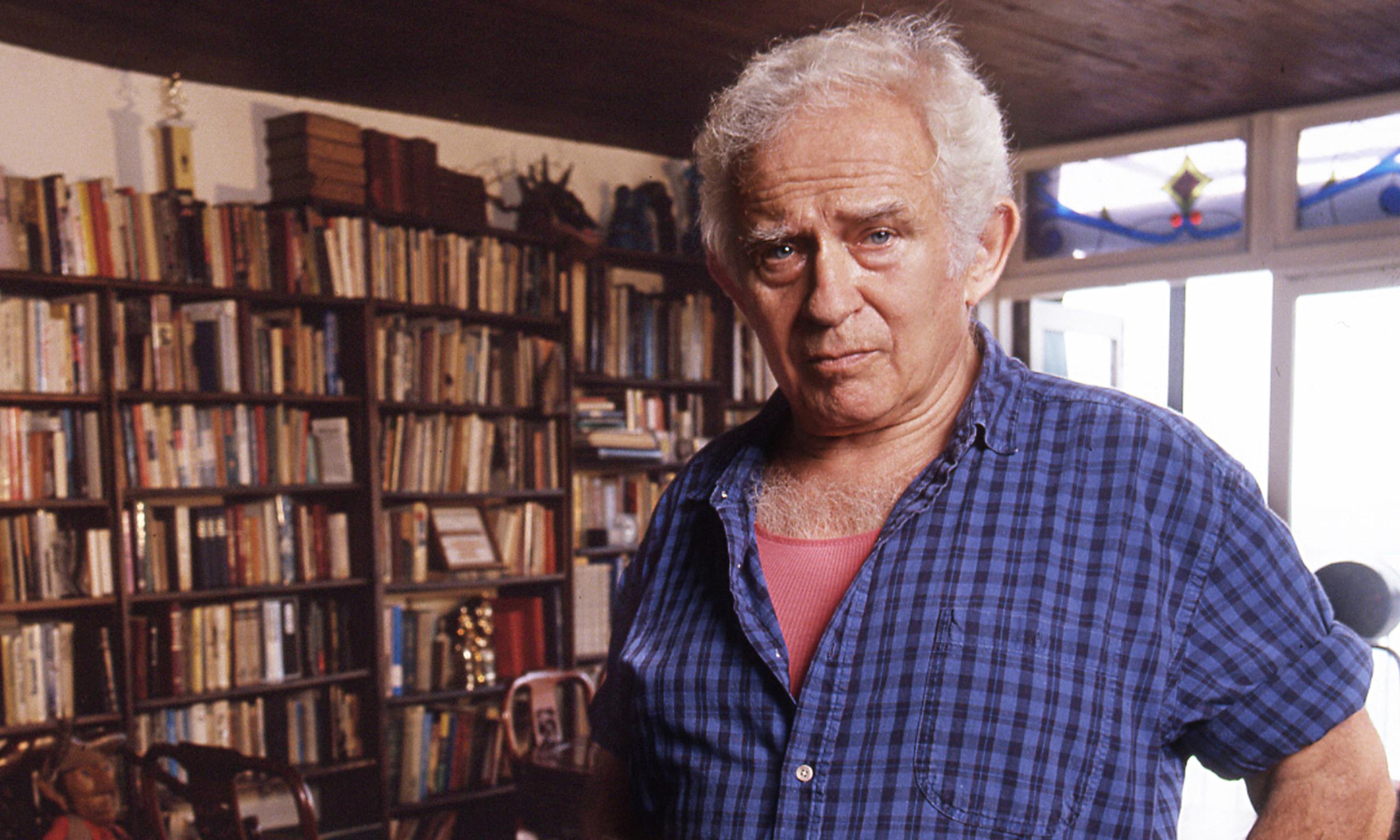

Norman’s “Mailer”

In reading The Armies of the Night, I have the distinct impression of reading something genuine. Something true in the way that truth can only be told by the novelist in a style that fits the time and event. This is not a Truth for all time, though within this situated truth is an echo of eternity. Norman Mailer’s truth is reflected through “the Novelist,” “the Participant,” “the Beast,” “the General,” “the Ruminant,” “the Prince of Bourbon”—all the facets of “Norman Mailer” who marched on the Pentagon in September 1967. Perhaps what makes Mailer’s narrative approach so genuine is the inconsistency of his narrator. It might be more accurate to say the consistently inconsistent narrator.

I’ve written before about Mailer’s Novelist, the novel, and The Armies of the Night, so I don’t have to rehash that here. What struck me about Mailer’s text this time was within the context of his earlier work, his particular emphasis on progress and growth, and how truth is relative and contingent.

If anything, Armies is about Mailer’s love affair with America. It’s tempestuous, unpredictable, and passionate. At one point he states: “What a mysterious country it was. The older he became, the more mysterious he found her.”[1] The “he” of course is Mailer’s persona in Armies, and “her,” America. As we see many times in Mailer’s work, America is schizophrenic: it is both Corporation Land and a place for revolution. The former represents the totalizing tendencies of those who want to control the hearts and minds of its citizens—those who have taken America from the “existential sanction of the frontier to the abstract ubiquitous sanction of the dollar bill.”[2] The latter are the disenfranchised, the disorderly—those who did not fit in neatly with the tenants of Technology Land and its war in Vietnam. Mailer becomes a reluctant participant in the revolution of the “hippies” who march on the symbol of corruption in the US: the Pentagon, “its pale yellow walls reminiscent of some plastic plug coming out of the hole made in flesh by an unmentionable operation.”[3]

The Pentagon stands for the corruption that must be rooted out. Mailer writes:

| “ | For years he had been writing about the nature of totalitarianism, its need to render population apathetic, its instrument — the destruction of mood. Mood was forever being sliced, cut, stamped, ground, excised, or obliterated; mood was a scent which rose from the acts and calms of nature, and totalitarianism was a deodorant to nature. Yes, and by the logic of this metaphor, the Pentagon looked like a five-sided tip on the spout of a spray can to be used under the arm, yes, the Pentagon was spraying the deodorant of its presence all over the fields of Virginia.[4] | ” |

The armies of the night were, then, the stinky and disorderly mobs from the pits of hell that Mailer found himself swept up in (see 3.5 “The Witches and the Fugs”[5] for the pagan bacchanal). Yet, despite Mailer’s reluctance—he did, after all, have Lowell’s party to attend that night in New York—the Observer becomes the Participant in a revolution that seems fit for the age. Mailer, like the hero of an epic, is tied to the fate of his country, and America, while partially defined by the increasing technology of the twentieth century, was also fickle. The Left was rallying their revolution to speak a different truth at the end of the sixties, and Mailer becomes its voice.

In “The White Negro,” Mailer argues that the tenuous state of history must be met by a new breed of American existentialist. The Hipster cannot remain the same, but continuously seeks new experiences and a new way to express himself. This hip morality is not only good for the individual, but also provides an example for his community: “One must grow or pay more for remaining the same.”[6] The Hipster practices a philosophical psychopathy that posits “new kinds of victories increase one’s power for new kinds of perception.”[7] Perhaps “Mailer” in Armies is a more mature hipster. He writes:

| “ | Just as the truth of his material was revealed to a good writer by the cutting edge of his style (he could thus hope his style was in each case the most appropriate tool for the material of the experience) so a revolutionary began to uncover the nature of his true situation by trying to ride the beast of his revolution. The idea behind these ideas was then obviously that the future of the revolution existed in the nerves and cells of the people who created it and lived with it, rather the the sanctity of the original idea.[8] | ” |

Ideas become ideologies after a while, conforming people’s nervous systems into something ersatz — plastic in flesh. The writer (I always thought Mailer’s Hipster was just a metaphor for the writer), then is not ruled by the idea, but renews his language and approach to fit the spirit of the time in the best way possible. Mailer’s Armies does just that: it is not a novel, nor is it journalism. It is a chronicle of a country seeking a new expression to free itself from the totalizing powers of Corporation Land. It’s message rings true for that particular time and place in America.

notes

- ↑ Mailer, Norman (1968). The Armies of the Night: History as a Novel, the Novel as History. New York: The New American library. p. 114.

- ↑ Mailer 1968, p. 158.

- ↑ Mailer 1968, p. 116.

- ↑ Mailer 1968, p. 117.

- ↑ Mailer 1968, pp. 116-129.

- ↑ Mailer, Norman (1992) [1959]. Advertisements for Myself. Cambridge: Harvard UP. pp. 349–50.

- ↑ Mailer 1992, p. 339.

- ↑ Mailer 1968, p. 88.