More actions

New entry. Need to add posts. |

m Added cat. |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{jt|title=''Lipton’s'': A Short Introduction}}{{refn|This is a short introduction for an article of excerpts that a magazine might publish.}} | {{jt|title=''Lipton’s'': A Short Introduction}}{{refn|This is a short introduction for an article of excerpts that a magazine might publish.}} | ||

{{dc|T}}{{start|he mid-1950s were a turbulent time for {{NM}}}}. His 1948 novel ''The Naked and the Dead | {{dc|T}}{{start|he mid-1950s were a turbulent time for {{NM}}}}. His 1948 novel ''The Naked and the Dead'' achieved significant success, receiving critical acclaim and maintaining bestseller status for over a year. His sophomore novel ''Barbary Shore'' (1951) was not as well received, and its negative critical reception left a lasting mark on Mailer, increasing the stakes for his third novel. Set against the backdrop of the Red Scare in Hollywood, ''The Deer Park'' was initially accepted for publication by Rinehart. However, it was later canceled by Stanley Rinehart due to Mailer’s refusal to remove a controversial scene. This rejection, which came just months before the planned publication date, was a significant blow to Mailer who saw this book as a chance to redeem his literary reputation and prove to himself that he was not an imposture. | ||

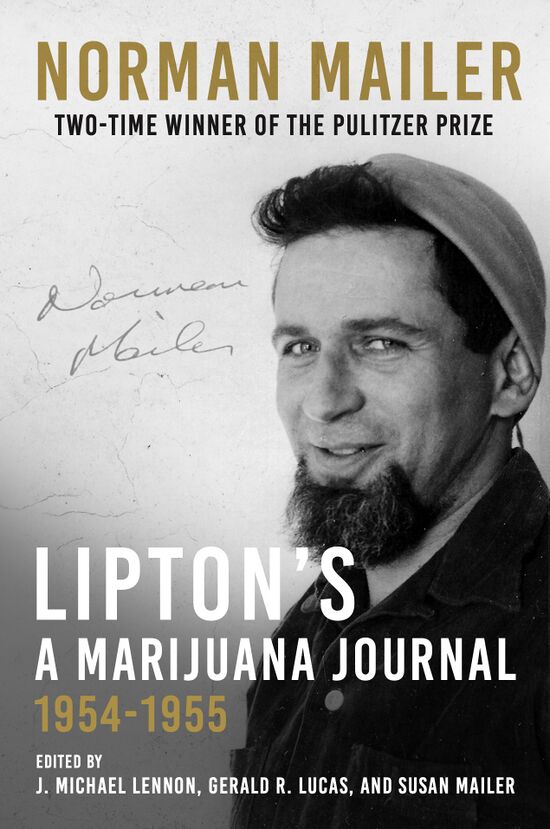

[[File:Liptons.jpg|thumb|550px|Preorder ''Lipton’s'' from [https://amzn.to/3WZSdWZ Amazon].]] | [[File:Liptons.jpg|thumb|550px|Preorder ''Lipton’s'' from [https://amzn.to/3WZSdWZ Amazon].]] | ||

During this | During this time, Mailer began a journal which he called “Lipton’s,” named after the slang for marijuana. The journal, which he started in December 1954, was a collection of musings that reflected his intellectual and creative processes, often recollected from his experiments with cannabis. The journal documents the effects of marijuana on his mental and physical states, in the vein of Thomas De Quincey’s ''Confessions of an English Opium-Eater''. Mailer described the ideas in “Lipton’s” as coming rapidly, a testament to his intense and often restive psyche. The journal spanned thirteen weeks, concluding in March 1955, and accumulated over 104,000 words across 708 entries. | ||

“Lipton’s” serves as an unflinching examination of Mailer’s intellectual capacities, literary ambitions, personal relationships, and psychological state in his early thirties. Mailer’s reflections in “Lipton’s” influenced many of his subsequent works, including his short fiction, his famous essay "The White Negro” (1957), and ''Advertisements for Myself'' (1959). The journal explores Mailer’s fascination with psychoanalysis, inspired by his readings of Freud and his circle, as well as the works of Wilhelm Reich, who linked sexual repression to societal norms. Mailer’s use of marijuana is portrayed as both a means of exploring his unconscious mind and a tool for enhancing various aspects of his life, from sexual performance to his appreciation of jazz. He believed the drug helped him marginalize his “despised image” of himself and embrace a more rebellious and authentic persona. However, the journal also reveals the darker side of his drug use, including moments of intense fear and visions of a divided, chaotic universe. | |||

Mailer’s relationship with psychoanalysis is a dominant theme in “Lipton’s.” After focusing on social and political themes in his early novels, he turned inward, aiming to bridge the gap between Freud’s theories and Marx’s ideas. This shift reflected his desire to understand the deeper psychological and symbolic underpinnings of human behavior and societal structures. Mailer’s engagement with psychoanalysis was further enriched by his relationship with Robert Lindner, a prominent psychoanalyst. Lindner’s book, ''Prescription for Rebellion'', which criticized the conformity | Mailer’s relationship with psychoanalysis is a dominant theme in “Lipton’s.” After focusing on social and political themes in his early novels, he turned inward, aiming to bridge the gap between Freud’s theories and Marx’s ideas. This shift reflected his desire to understand the deeper psychological and symbolic underpinnings of human behavior and societal structures. Mailer’s engagement with psychoanalysis was further enriched by his relationship with Robert Lindner, a prominent psychoanalyst. Lindner’s book, ''Prescription for Rebellion'', which criticized the conformity wrought by popular psychoanalysis, resonated deeply with Mailer. Lindner argued that rebellion was a natural response to societal repression, a view that Mailer found compelling. | ||

Mailer and Lindner developed a close friendship, exchanging ideas through letters and conversations. Mailer even sought Lindner’s professional analysis, which Lindner declined for fear it would harm their friendship. Their intellectual exchange profoundly influenced Mailer, who referred to their dialogue as “inter-fecundation.” Lindner’s insights and support helped Mailer navigate his creative and psychological challenges during this period, and their friendship lasted until Lindner’s untimely death from congenital heart disease in 1956. | Mailer and Lindner developed a close friendship, exchanging ideas through letters and conversations. Mailer even sought Lindner’s professional analysis, which Lindner declined for fear it would harm their friendship. Their intellectual exchange profoundly influenced Mailer, who referred to their dialogue as “inter-fecundation.” Lindner’s insights and support helped Mailer navigate his creative and psychological challenges during this period, and their friendship lasted until Lindner’s untimely death from congenital heart disease in 1956. | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

{{* * *}} | {{* * *}} | ||

The following excerpts exemplify the deeply introspective and honest | The following excerpts exemplify the deeply introspective and honest analysis in “Lipton’s.” They address the duality of human nature, the conflicts between societal norms and personal authenticity, identity and existence—including sexuality, creativity, rebellion, and mortality. | ||

. . . | '''46''': What worries me today and other days is that I am playing an enormous deception on myself, and that I embark on these thoughts only to make myself more interesting, more complex to other people, more complex to myself. My vanity is so enormous. Perhaps I do all this to demonstrate to my audience that I too can create mystic spiritual characters. But on the other hand, these remarks can be merely my fear of what lies ahead. I love the world so much, I am so fascinated by it, that I dread the possibility that someday I may travel so far that I wish to relinquish it. What is important is that I think for the first time in years I’m growing quickly again. | ||

'''63''': The measurement of time is as necessary to society as the vision of space filled and space unfilled is to the soul. So Lipton’s which destroys the sense of time also destroys the sense of society and opens the soul. | |||

'''69''': “Vested interest” is enormously more powerful than we think. It is society’s substitute for the soul, and the abstract man who lives totally in society has no identity, no “I” other than his vested interest. Which in its extreme case is an explanation of the totalitarian personality. It is vested interest which allows us to dismiss other people, to say of them that they are Negroes, Jews, homosexuals, anal-compulsives, hysterics, hicks, city slickers, etc. In effect, by putting a label on a person we commit assassination, we cease to allow them existence in our minds. The echo of the word “liquidate” is “to petrifact,” and that is what the Stalinist does. He can kill by categories because the categories have become lifeless to him, no more than concepts. | |||

'''85''': What characterizes the psychology of the saint, the artist, the criminal, the mad perhaps, the athlete, the warrior, the revolutionary, the entertainer, the libertine, the drug addict, the gambler, the alcoholic, the demagogue, and all the other varieties of the adventurer, the explorer is that they have the boldness to believe that they are truly unique, and will not necessarily be punished like others. Also true of the victim who believes that he or she is unique and so will not be impoverished by the drunkard, raped by the sadist, murdered by the murderer. The victim is the passive complement to the adventurer. My mother as victim, my father as adventurer.[1] I, who have always been the adventurer (although enormously suppressed) have never been able to have love affairs with victims—they are too much like my mother. So I have searched out women who were adventurers—which is why virgins have never appealed to me. | |||

'''102''': The hipster is the adventurer beneath the surface of society, the murderer who moves among social animals, and he is also the saint, but he dreams of a heaven on earth. So; predictions: Hipsters are the proletariat of the future. | |||

'''103''': Given my intellectual verbal mind. Lipton’s was a great aid. To a poor bootblack, it probably can do no more than ease him from an intolerable existence into a cloudy nothingness. That is my great adventure with Lipton’s. I will journey into myself with the hope that I, the adventurer, can come out without being destroyed. But I am terrified. I don’t think I have ever been so frightened in my life. | |||

'''138''': My ambition remains my contact with the world, and perhaps it is not all bad—I would certainly prefer to be a genius than a saint. That is why Bob [Lindner] is right about the petty Hitler in me. I have to do it all, all by myself With the others, I am competitive. Every bit of evidence I see, as in television, of hipsterism makes me worry, “My God, somebody may do it before I do it.” No fear of me becoming a saint. | |||

'''140''': All churches say, “Be content.” They are always opposed to change for they are the bastardization of the soul in society. Freud went very far, and indeed he started on cocaine I suspect, got his first intimations of the caverns below. He was a very great man, but no great man can do it all, and Freud stopped short for which one can hardly blame him. (Look, what happened to Wilhelm Reich.) Freud stopped with the idea that society is good rather than that society is necessary until man conquers nature, but the society must in its turn be conquered or man will be destroyed. | |||

'''155''': Bob Lindner. As he reads this note, he is going to think I am sniping at him again, and he doesn’t understand my feelings here. I am not sniping at him—if I were, I would not send him these notes, for my competitive feelings would say, “He may take them a step beyond you, and he’ll get the credit.” But Bob is one of the few people I don’t feel competitive toward. I feel we could have a Marx and Engels relation, and leave the matter of who’s Marx aside until we both have grown. | |||

'''158''': The homo-erotic corollary. This is for Bob Lindner. I start with the premise that all men and women are bi-sexual. I believe this is natural. It is true for animals, and it makes sense, for love is best when it’s unified (at last I find some agreement with analyst, although what a difference) and when we love someone we would make love with them, if society did not prevent it or make it so painful. Given my premise, the pure heterosexual is a cripple—society has completely submerged one half of his nature. So, too, is the pure homosexual—and I suspect that pure homosexuals are invariably very unfleshly. People like [André] Gide have denied their bodies, and sex is invariably painful to them, although in recompense their minds have saintly qualities. (Gide and Gertrude Stein). | |||

'''162''': One of the curious effects of Lipton’s is that it seems to take away my neurosis and expose me to all that is saintly and psychopathic in my character. Just enough Lipton’s, and being alone with Adele, and the psychopathy is pleasantly expressed in fucking, and afterward I feel truly saintly and love everyone and am filled with compassion for mankind. But when I take Lipton’s after being pretty strenuously fucked-out, especially if people are around, then the amount of psychopathy in me is frightening. | |||

'''199''': Looking at myself in the mirror, high on Lipton’s, I saw myself as follows: The left side of my face is comparatively heavy, sensual, possessor of hard masculine knowledge, strong, proud, and vain. Seen front-face I appear nervous, irresolute, tender, anxious, vulnerable, earnest, and Jewish middle-class. The right side of my face is boyish, saintly, bisexual, psychopathic, and suggest the victim. | |||

'''201''': When we run across something we don’t understand, and casually throw it out or ignore it, it is because we understand it much too well. This is true of all rejection. As a corollary: What we erase is what we wish to emphasize. So the good writer crosses out the bad writing (the clichés) with which the ambitious part of his being had hoped to attract the public. Literary style is always the record of the war within a man. | |||

'''223''': Homeostasis and sociostasis. I am going to postulate that there is not only homeostasis, (which is the most healthy act possible at any moment for the soul), but there is sociostasis which is the health of society. The sociostatic element in man is placed there by society which resists and wars and retreats against the inroads of homeostasis, which is the personal healthy rebellious and soul-ful expression of man. In the course of a human’s life the child is born all homeostatic (unless the mother has communicated sociostatic components to the embryo), but generally the years of childhood are years in which the homeostatic principle or life-force is blocked, contained, damned, and even destroyed by the creation of sociostatic elements—the child is partially turned into someone who will serve the purposes of society. The essential animal-soul life is contained, forced underground, denied. | |||

'''263''': Since I started this Journal I have been feeling happier than I have in my whole life. So much has been released and so much created—because for me release and creation are parallel expressions of the same thing. But underneath it persists a feeling that I am going to die soon which perhaps is why I entrust each installment of the journal to [Robert Lindner] in the mails. I even caught myself thinking that perhaps I would write at this journal for the next year or two, and there would be thousands of pages, and then pop I would go—which makes me sad rather than depressed because for the first time in my life I really want to live. | |||

'''280''': Reason has now become Rationalization . . . Small communities refuse the fluoridation of water, although rationally fluoridation prevents tooth decay and does no known harm. [Senator Joseph] McCarthys spring up and have to be defeated at what cost to the rational nervous system of the State it is difficult to contemplate. Demagogues are on the march, painting deserts the representational—to wit, the rational. Poetry ceases to communicate to large audiences. Billy Graham’s electrify the staid English, Aldous Huxley, the last in line of a great intellectual family takes a drug and writes a book about it. The demagogue is everywhere. Millions give themselves to the gibberish of television. Be-bop floods America after the war, and it is the artistic expression of double-talk (ultimately the expression of many things at once). Monsters in uniform murder in the name of the state until finally the state itself is caught in contradiction. It is killing its own. It is possible that at this moment in history the irrational expressions of man are more healthy than the rational. For state-planners, and civic planners and community planners are always rattled, bewildered, rendered anxious by the totally irrational. McCarthy fucked up the confidence of the American State more completely than a million Communist Party members could have. | |||

'''284''': I have to face something. Just as the pompous man encourages rebellion, so I wonder if I as the ''enfant terrible'', the pint-sized Hitler, the outrageous radical, am not encouraging conformity. I take out the Lipton’s, and people who were previously drawn to me flee the house. Possibly, my mother planted her deep conservative seeds. Certainly, there is a vast conservative echo in me. But I am expressing things which have to do with life and with man’s goodness so people who flee come back again. The only thing is that if I keep on the way I’m going, they’ll have to come to visit me during jail hours. | |||

'''359''': Power-mad men court disaster. They have to. They can never retreat. Which is why [Sen. Joseph] McCarthy went down although he was given every opportunity to compromise—indeed they finally had to squash him legislatively because they had become terrified of him—unlike other legislators he was not a social being—also true of all power-mad men. He was an animal. . . . But that also accounts for why he had his strength, may have it again, and why so many people including myself had a sneaking attraction toward him, not because of his ideas, but because of his person. The same is true for Hitler and the Germans, and the plan of the Junker generals to assassinate Hitler. | |||

'''524''': Adele gets furious these days when I talk about bisexuality. Why don’t you become a homosexual, she flares at me, you want to anyway. The funny thing is that I don’t—I feel less homosexual tension than I have ever felt—neither homosexual desire which for that matter I’ve never felt consciously, but more important no homosexual anxiety. The other day in a homosexual clothing store the salesman was giving me a covert feel while measuring the length of the cuffs. A year ago I would have broken out into a sweat. This time I stood there unmoved but feeling tenderly humorous toward him… Instead, I thought, “Well, my friend, congratulations. A part of me always wanted to be a corset adjuster so I could cop quick feels (and isn’t that just the sexual quality of the cop—he always takes as a stranger) and get away with it. And you on your side of the fence have made it. | |||

'''567''': Adele often comments in our bed, “Why are you frowning so? You look in pain? You look angry and tortured”? Every time she makes such a remark I am in the process of trying to shape a thought into an idea. I am trying to give birth. My mighty mother is in me, but I have books, ideas, projects, theses, etc., instead of birthing children. | |||

'''579''': Last night taking my Seconal I thought—“A pill for the swill”. And I was flat (stunned) by the recognition. How I hate this journal, hate myself, hate Adele, hate my wild kick, hate the garbage I release, how I cling to society to knock me out, to stun my rebellion. If I ever go insane I’ll not be a schizo. I’ll be a manic-depressive. Adele will too. For we either love each other or hate each other. But my salvation is for my honesty to hunt the crook in me forever. Only through understanding myself can I come to create. By going in, I can give out. As I understand myself, and understand Adele (for whom sensuality is the equivalent of speech for me) so I can waste less time. These days I’m consumed with impatience which comes out in the barely suppressed pompousness and sense of rightness with which I talk even to dear friends. | |||

'''695''': Where Bob Lindner is wrong about the novel is that he doesn’t understand the peculiar communicating power of the novel. The novel goes from writer’s-thought to reader’s-thought by the use of an oblique (obliging) symbol, expression, or montage. It does not enter the more paralyzing process, more accurately limiting process, of converting thought to idea in order that the receiver can then try to let the idea enter in order that he take thought. Which is why I cannot write a novel when I know what I want to say. It comes out too thin, too ideated. My best scenes are the ones where I didn’t know what I was doing when I did it. Few artists have ever been able to work on the thought-idea-thought interchange. And their weakness was often there, as Gide for instance. I must always tackle the novels I do not understand. Which is why Lipton’s has stripped me of my next ten years of books. The ideas here would have come out obliquely in the books I blundered through. Now I have to take an enormous step, and my capacities may not be equal to it. Still, I don’t regret the too-quick opening, the great take of these past few months. I had to, for my health, and besides one should always try for more, not less. That’s the only real health. | |||

'''704''': I have been going through terrifying inner experiences. Last Friday night when I took Lipton’s I was already in a state of super-excitation which means intense muscular tension for me. When the Lipton’s hit, and it hit with a great jolt, it was my first in a week, I felt as if every one of my nerves were jumping free. The amount of thought which was released was fantastic. I had nothing less than a vision of the universe which it would take me forever to explain. I also knew that I was smack on the edge of insanity, that I was wandering through all the mountain craters of schizophrenia. I knew I could come back, I was like an explorer who still had a life-line out of the caverns, but I understood also that it would not be all that difficult to cut the life line. Insanity comes from obeying a hunch—it is a premature freezing of perceptions—one takes off into cloud even before one has properly prepared the ground, and one gives all to an “unrealistic” appreciation of one’s genius. So I knew and this is my health that it is as important to return, to give, to study, to be deprived of cloud seven as it is to stay on it. One advances forward into the unknown by going forward and then retreating back. Only the hunch player decides to cast all off and try to go all the way. What I ended up with was a sort of existentialism I imagine although I know nothing of existentialism (Everybody accuses me these days of being an existentialist). Anyway, the communicable part of my vision was that everything is valid and that nothing is knowable—one simply cannot erect a value with the confidence that it is good for others—all one can do is know what is good, that is what is necessary for oneself, and one must act on that basis, for underlying the conception is the philosophical idea that for life to expand at its best, everybody must express themselves at their best, and the value of the rebel and the radical is that he seeks to expand that part of the expanding sphere (of totality) which is most retarded. Deep in the vision action seemed trivial which is why I knew the cold graveyard of schizophrenia. Out of the vision I had a happier tolerance. I could deal with people like Catholics and ''saidsists'' sadists because I was not worried about who would win the way I used to be. And indeed I learned the way to handle sadists—there are only two ways: One must wither be capable of generating more force, of terrifying them, or else one must dazzle and confuse them. | |||

'''705'''. Tonight people are coming over and we’ll have a Lipton’s party. I half don’t want it. Last weekend with its Lipton’s carried me flying half-way through the week and dumped me in depression these last two days. Now I’m finally coming out of it and it’d be interesting to see how I would act next week. But on with the fuckanalysis. | |||

{{Notes}} | {{Notes}} | ||

| Line 25: | Line 71: | ||

{{2024}} | {{2024}} | ||

[[Category:05/2024]] | [[Category:05/2024]] | ||

[[Category:Lipton’s]] | |||

Latest revision as of 09:02, 18 June 2024

Lipton’s: A Short Introduction[1]

The mid-1950s were a turbulent time for Norman Mailer. His 1948 novel The Naked and the Dead achieved significant success, receiving critical acclaim and maintaining bestseller status for over a year. His sophomore novel Barbary Shore (1951) was not as well received, and its negative critical reception left a lasting mark on Mailer, increasing the stakes for his third novel. Set against the backdrop of the Red Scare in Hollywood, The Deer Park was initially accepted for publication by Rinehart. However, it was later canceled by Stanley Rinehart due to Mailer’s refusal to remove a controversial scene. This rejection, which came just months before the planned publication date, was a significant blow to Mailer who saw this book as a chance to redeem his literary reputation and prove to himself that he was not an imposture.

During this time, Mailer began a journal which he called “Lipton’s,” named after the slang for marijuana. The journal, which he started in December 1954, was a collection of musings that reflected his intellectual and creative processes, often recollected from his experiments with cannabis. The journal documents the effects of marijuana on his mental and physical states, in the vein of Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. Mailer described the ideas in “Lipton’s” as coming rapidly, a testament to his intense and often restive psyche. The journal spanned thirteen weeks, concluding in March 1955, and accumulated over 104,000 words across 708 entries.

“Lipton’s” serves as an unflinching examination of Mailer’s intellectual capacities, literary ambitions, personal relationships, and psychological state in his early thirties. Mailer’s reflections in “Lipton’s” influenced many of his subsequent works, including his short fiction, his famous essay "The White Negro” (1957), and Advertisements for Myself (1959). The journal explores Mailer’s fascination with psychoanalysis, inspired by his readings of Freud and his circle, as well as the works of Wilhelm Reich, who linked sexual repression to societal norms. Mailer’s use of marijuana is portrayed as both a means of exploring his unconscious mind and a tool for enhancing various aspects of his life, from sexual performance to his appreciation of jazz. He believed the drug helped him marginalize his “despised image” of himself and embrace a more rebellious and authentic persona. However, the journal also reveals the darker side of his drug use, including moments of intense fear and visions of a divided, chaotic universe.

Mailer’s relationship with psychoanalysis is a dominant theme in “Lipton’s.” After focusing on social and political themes in his early novels, he turned inward, aiming to bridge the gap between Freud’s theories and Marx’s ideas. This shift reflected his desire to understand the deeper psychological and symbolic underpinnings of human behavior and societal structures. Mailer’s engagement with psychoanalysis was further enriched by his relationship with Robert Lindner, a prominent psychoanalyst. Lindner’s book, Prescription for Rebellion, which criticized the conformity wrought by popular psychoanalysis, resonated deeply with Mailer. Lindner argued that rebellion was a natural response to societal repression, a view that Mailer found compelling.

Mailer and Lindner developed a close friendship, exchanging ideas through letters and conversations. Mailer even sought Lindner’s professional analysis, which Lindner declined for fear it would harm their friendship. Their intellectual exchange profoundly influenced Mailer, who referred to their dialogue as “inter-fecundation.” Lindner’s insights and support helped Mailer navigate his creative and psychological challenges during this period, and their friendship lasted until Lindner’s untimely death from congenital heart disease in 1956.

Mailer’s relationship with his second wife, Adele Morales, also figures prominently in the journal. Their marriage, which began in April 1954, was marked by emotional intensity and creative stimulation. Morales, a dark, sensuous artist, contrasted sharply with Mailer’s first wife Beatrice Silverman and played a significant role in his exploration of freedom and living a more authentic life. Mailer’s love for Adele is evident throughout the journal, although their relationship later deteriorated, culminating in a violent altercation in 1960.

“Lipton’s” marks a critical point in Mailer’s development as a writer, showcasing his emerging literary style and his recognition of the importance of voice and public persona that he would later hone, particularly in AFM where he attempted to incite “a revolution in the consciousness of our time.” In his journal, he experimented with new forms of expression, which later culminated in his work for the Village Voice and his more mature writing. The journal is a rich, frenetic, contradictory, and complex mixture of ideas and reflections, documenting Mailer’s quest for personal and artistic authenticity amidst the broader cultural and intellectual currents of his time. It captures his intellectual curiosity, his experiments with psychoanalysis, philosophy, metaphysics, and marijuana, and his efforts to carve out a distinctive literary voice. The journal documents Mailer’s quest for personal and artistic authenticity amidst the complexities of mid-20th-century America.

The following excerpts exemplify the deeply introspective and honest analysis in “Lipton’s.” They address the duality of human nature, the conflicts between societal norms and personal authenticity, identity and existence—including sexuality, creativity, rebellion, and mortality.

46: What worries me today and other days is that I am playing an enormous deception on myself, and that I embark on these thoughts only to make myself more interesting, more complex to other people, more complex to myself. My vanity is so enormous. Perhaps I do all this to demonstrate to my audience that I too can create mystic spiritual characters. But on the other hand, these remarks can be merely my fear of what lies ahead. I love the world so much, I am so fascinated by it, that I dread the possibility that someday I may travel so far that I wish to relinquish it. What is important is that I think for the first time in years I’m growing quickly again.

63: The measurement of time is as necessary to society as the vision of space filled and space unfilled is to the soul. So Lipton’s which destroys the sense of time also destroys the sense of society and opens the soul.

69: “Vested interest” is enormously more powerful than we think. It is society’s substitute for the soul, and the abstract man who lives totally in society has no identity, no “I” other than his vested interest. Which in its extreme case is an explanation of the totalitarian personality. It is vested interest which allows us to dismiss other people, to say of them that they are Negroes, Jews, homosexuals, anal-compulsives, hysterics, hicks, city slickers, etc. In effect, by putting a label on a person we commit assassination, we cease to allow them existence in our minds. The echo of the word “liquidate” is “to petrifact,” and that is what the Stalinist does. He can kill by categories because the categories have become lifeless to him, no more than concepts.

85: What characterizes the psychology of the saint, the artist, the criminal, the mad perhaps, the athlete, the warrior, the revolutionary, the entertainer, the libertine, the drug addict, the gambler, the alcoholic, the demagogue, and all the other varieties of the adventurer, the explorer is that they have the boldness to believe that they are truly unique, and will not necessarily be punished like others. Also true of the victim who believes that he or she is unique and so will not be impoverished by the drunkard, raped by the sadist, murdered by the murderer. The victim is the passive complement to the adventurer. My mother as victim, my father as adventurer.[1] I, who have always been the adventurer (although enormously suppressed) have never been able to have love affairs with victims—they are too much like my mother. So I have searched out women who were adventurers—which is why virgins have never appealed to me.

102: The hipster is the adventurer beneath the surface of society, the murderer who moves among social animals, and he is also the saint, but he dreams of a heaven on earth. So; predictions: Hipsters are the proletariat of the future.

103: Given my intellectual verbal mind. Lipton’s was a great aid. To a poor bootblack, it probably can do no more than ease him from an intolerable existence into a cloudy nothingness. That is my great adventure with Lipton’s. I will journey into myself with the hope that I, the adventurer, can come out without being destroyed. But I am terrified. I don’t think I have ever been so frightened in my life.

138: My ambition remains my contact with the world, and perhaps it is not all bad—I would certainly prefer to be a genius than a saint. That is why Bob [Lindner] is right about the petty Hitler in me. I have to do it all, all by myself With the others, I am competitive. Every bit of evidence I see, as in television, of hipsterism makes me worry, “My God, somebody may do it before I do it.” No fear of me becoming a saint.

140: All churches say, “Be content.” They are always opposed to change for they are the bastardization of the soul in society. Freud went very far, and indeed he started on cocaine I suspect, got his first intimations of the caverns below. He was a very great man, but no great man can do it all, and Freud stopped short for which one can hardly blame him. (Look, what happened to Wilhelm Reich.) Freud stopped with the idea that society is good rather than that society is necessary until man conquers nature, but the society must in its turn be conquered or man will be destroyed.

155: Bob Lindner. As he reads this note, he is going to think I am sniping at him again, and he doesn’t understand my feelings here. I am not sniping at him—if I were, I would not send him these notes, for my competitive feelings would say, “He may take them a step beyond you, and he’ll get the credit.” But Bob is one of the few people I don’t feel competitive toward. I feel we could have a Marx and Engels relation, and leave the matter of who’s Marx aside until we both have grown.

158: The homo-erotic corollary. This is for Bob Lindner. I start with the premise that all men and women are bi-sexual. I believe this is natural. It is true for animals, and it makes sense, for love is best when it’s unified (at last I find some agreement with analyst, although what a difference) and when we love someone we would make love with them, if society did not prevent it or make it so painful. Given my premise, the pure heterosexual is a cripple—society has completely submerged one half of his nature. So, too, is the pure homosexual—and I suspect that pure homosexuals are invariably very unfleshly. People like [André] Gide have denied their bodies, and sex is invariably painful to them, although in recompense their minds have saintly qualities. (Gide and Gertrude Stein).

162: One of the curious effects of Lipton’s is that it seems to take away my neurosis and expose me to all that is saintly and psychopathic in my character. Just enough Lipton’s, and being alone with Adele, and the psychopathy is pleasantly expressed in fucking, and afterward I feel truly saintly and love everyone and am filled with compassion for mankind. But when I take Lipton’s after being pretty strenuously fucked-out, especially if people are around, then the amount of psychopathy in me is frightening.

199: Looking at myself in the mirror, high on Lipton’s, I saw myself as follows: The left side of my face is comparatively heavy, sensual, possessor of hard masculine knowledge, strong, proud, and vain. Seen front-face I appear nervous, irresolute, tender, anxious, vulnerable, earnest, and Jewish middle-class. The right side of my face is boyish, saintly, bisexual, psychopathic, and suggest the victim.

201: When we run across something we don’t understand, and casually throw it out or ignore it, it is because we understand it much too well. This is true of all rejection. As a corollary: What we erase is what we wish to emphasize. So the good writer crosses out the bad writing (the clichés) with which the ambitious part of his being had hoped to attract the public. Literary style is always the record of the war within a man.

223: Homeostasis and sociostasis. I am going to postulate that there is not only homeostasis, (which is the most healthy act possible at any moment for the soul), but there is sociostasis which is the health of society. The sociostatic element in man is placed there by society which resists and wars and retreats against the inroads of homeostasis, which is the personal healthy rebellious and soul-ful expression of man. In the course of a human’s life the child is born all homeostatic (unless the mother has communicated sociostatic components to the embryo), but generally the years of childhood are years in which the homeostatic principle or life-force is blocked, contained, damned, and even destroyed by the creation of sociostatic elements—the child is partially turned into someone who will serve the purposes of society. The essential animal-soul life is contained, forced underground, denied.

263: Since I started this Journal I have been feeling happier than I have in my whole life. So much has been released and so much created—because for me release and creation are parallel expressions of the same thing. But underneath it persists a feeling that I am going to die soon which perhaps is why I entrust each installment of the journal to [Robert Lindner] in the mails. I even caught myself thinking that perhaps I would write at this journal for the next year or two, and there would be thousands of pages, and then pop I would go—which makes me sad rather than depressed because for the first time in my life I really want to live.

280: Reason has now become Rationalization . . . Small communities refuse the fluoridation of water, although rationally fluoridation prevents tooth decay and does no known harm. [Senator Joseph] McCarthys spring up and have to be defeated at what cost to the rational nervous system of the State it is difficult to contemplate. Demagogues are on the march, painting deserts the representational—to wit, the rational. Poetry ceases to communicate to large audiences. Billy Graham’s electrify the staid English, Aldous Huxley, the last in line of a great intellectual family takes a drug and writes a book about it. The demagogue is everywhere. Millions give themselves to the gibberish of television. Be-bop floods America after the war, and it is the artistic expression of double-talk (ultimately the expression of many things at once). Monsters in uniform murder in the name of the state until finally the state itself is caught in contradiction. It is killing its own. It is possible that at this moment in history the irrational expressions of man are more healthy than the rational. For state-planners, and civic planners and community planners are always rattled, bewildered, rendered anxious by the totally irrational. McCarthy fucked up the confidence of the American State more completely than a million Communist Party members could have.

284: I have to face something. Just as the pompous man encourages rebellion, so I wonder if I as the enfant terrible, the pint-sized Hitler, the outrageous radical, am not encouraging conformity. I take out the Lipton’s, and people who were previously drawn to me flee the house. Possibly, my mother planted her deep conservative seeds. Certainly, there is a vast conservative echo in me. But I am expressing things which have to do with life and with man’s goodness so people who flee come back again. The only thing is that if I keep on the way I’m going, they’ll have to come to visit me during jail hours.

359: Power-mad men court disaster. They have to. They can never retreat. Which is why [Sen. Joseph] McCarthy went down although he was given every opportunity to compromise—indeed they finally had to squash him legislatively because they had become terrified of him—unlike other legislators he was not a social being—also true of all power-mad men. He was an animal. . . . But that also accounts for why he had his strength, may have it again, and why so many people including myself had a sneaking attraction toward him, not because of his ideas, but because of his person. The same is true for Hitler and the Germans, and the plan of the Junker generals to assassinate Hitler.

524: Adele gets furious these days when I talk about bisexuality. Why don’t you become a homosexual, she flares at me, you want to anyway. The funny thing is that I don’t—I feel less homosexual tension than I have ever felt—neither homosexual desire which for that matter I’ve never felt consciously, but more important no homosexual anxiety. The other day in a homosexual clothing store the salesman was giving me a covert feel while measuring the length of the cuffs. A year ago I would have broken out into a sweat. This time I stood there unmoved but feeling tenderly humorous toward him… Instead, I thought, “Well, my friend, congratulations. A part of me always wanted to be a corset adjuster so I could cop quick feels (and isn’t that just the sexual quality of the cop—he always takes as a stranger) and get away with it. And you on your side of the fence have made it.

567: Adele often comments in our bed, “Why are you frowning so? You look in pain? You look angry and tortured”? Every time she makes such a remark I am in the process of trying to shape a thought into an idea. I am trying to give birth. My mighty mother is in me, but I have books, ideas, projects, theses, etc., instead of birthing children.

579: Last night taking my Seconal I thought—“A pill for the swill”. And I was flat (stunned) by the recognition. How I hate this journal, hate myself, hate Adele, hate my wild kick, hate the garbage I release, how I cling to society to knock me out, to stun my rebellion. If I ever go insane I’ll not be a schizo. I’ll be a manic-depressive. Adele will too. For we either love each other or hate each other. But my salvation is for my honesty to hunt the crook in me forever. Only through understanding myself can I come to create. By going in, I can give out. As I understand myself, and understand Adele (for whom sensuality is the equivalent of speech for me) so I can waste less time. These days I’m consumed with impatience which comes out in the barely suppressed pompousness and sense of rightness with which I talk even to dear friends.

695: Where Bob Lindner is wrong about the novel is that he doesn’t understand the peculiar communicating power of the novel. The novel goes from writer’s-thought to reader’s-thought by the use of an oblique (obliging) symbol, expression, or montage. It does not enter the more paralyzing process, more accurately limiting process, of converting thought to idea in order that the receiver can then try to let the idea enter in order that he take thought. Which is why I cannot write a novel when I know what I want to say. It comes out too thin, too ideated. My best scenes are the ones where I didn’t know what I was doing when I did it. Few artists have ever been able to work on the thought-idea-thought interchange. And their weakness was often there, as Gide for instance. I must always tackle the novels I do not understand. Which is why Lipton’s has stripped me of my next ten years of books. The ideas here would have come out obliquely in the books I blundered through. Now I have to take an enormous step, and my capacities may not be equal to it. Still, I don’t regret the too-quick opening, the great take of these past few months. I had to, for my health, and besides one should always try for more, not less. That’s the only real health.

704: I have been going through terrifying inner experiences. Last Friday night when I took Lipton’s I was already in a state of super-excitation which means intense muscular tension for me. When the Lipton’s hit, and it hit with a great jolt, it was my first in a week, I felt as if every one of my nerves were jumping free. The amount of thought which was released was fantastic. I had nothing less than a vision of the universe which it would take me forever to explain. I also knew that I was smack on the edge of insanity, that I was wandering through all the mountain craters of schizophrenia. I knew I could come back, I was like an explorer who still had a life-line out of the caverns, but I understood also that it would not be all that difficult to cut the life line. Insanity comes from obeying a hunch—it is a premature freezing of perceptions—one takes off into cloud even before one has properly prepared the ground, and one gives all to an “unrealistic” appreciation of one’s genius. So I knew and this is my health that it is as important to return, to give, to study, to be deprived of cloud seven as it is to stay on it. One advances forward into the unknown by going forward and then retreating back. Only the hunch player decides to cast all off and try to go all the way. What I ended up with was a sort of existentialism I imagine although I know nothing of existentialism (Everybody accuses me these days of being an existentialist). Anyway, the communicable part of my vision was that everything is valid and that nothing is knowable—one simply cannot erect a value with the confidence that it is good for others—all one can do is know what is good, that is what is necessary for oneself, and one must act on that basis, for underlying the conception is the philosophical idea that for life to expand at its best, everybody must express themselves at their best, and the value of the rebel and the radical is that he seeks to expand that part of the expanding sphere (of totality) which is most retarded. Deep in the vision action seemed trivial which is why I knew the cold graveyard of schizophrenia. Out of the vision I had a happier tolerance. I could deal with people like Catholics and saidsists sadists because I was not worried about who would win the way I used to be. And indeed I learned the way to handle sadists—there are only two ways: One must wither be capable of generating more force, of terrifying them, or else one must dazzle and confuse them.

705. Tonight people are coming over and we’ll have a Lipton’s party. I half don’t want it. Last weekend with its Lipton’s carried me flying half-way through the week and dumped me in depression these last two days. Now I’m finally coming out of it and it’d be interesting to see how I would act next week. But on with the fuckanalysis.

notes

- ↑ This is a short introduction for an article of excerpts that a magazine might publish.