Happy Publication Day

Well it’s official: Lipton’s has been published. You know what to do, if you have not already. Not only grab a copy or two, but please leave a good review; much appreciated. I have been working on Lipton’s in some form for over five years, and Susan and Mike have been even longer. I was happy to lend my expertise, especially on the DH project that we published a couple of years ago. It’s really been a labor of love. I’d love to hear what you think.

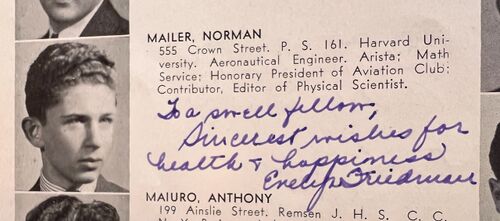

Today, I’m starting with some juvenilia from Mailer, a box that for some reason (no specific dates?) was not at the beginning of the database: Box 879. There are about a dozen stories and fragments, a journal entry about swimming in the Atlantic when he was 12, and other miscellaneous stuff. From his “Senior Recorder” from Boys High School, dated June 1939, I found Mailer’s photo. While some of this might be fascinating and germane to getting a complete picture of Mailer’s later work, it’s likely of more interest to a biographer rather than a literary scholar. I guess it’s back to the correspondence.

I have to go through a lot of letters before I get the occasional gem like this one, dated October 17, 1956, emphasis mine:

| “ | I’m glad you enjoyed “The Man Who Studied Yoga.” I wrote it about four years ago, and so for the first time in my life I’ve had the experience of being fairly removed from something of mine in print. But I am pleased that you and Irving and Mills liked it because I think that piece may be the beginning of a general tendency for me—not so much as a question of material, as style or view or whatever. | ” |

Oh, agreed, Norman. “Yoga” is a major transition, stylistically and thematically—perhaps more so the latter. The important part about “Yoga” is the failure of Sam Slovada—a figure in many ways based on Mailer himself. The story is full of images of waste and excrement, something that, like kipple, is slowly draining the life out of Sam. Sam longs for fulfillment and passion, but he only gets glimpses of those things now as he slides into obscurity and irrelevancy. Mailer wrote “Yoga” as the prologue to The Deer Park early in 1952. This is the point where Mailer decides that he truly is a writer—or at least he will give his all to become one. And that’s the point: Mailer steps up to the challenge, not knowing what will happen, and embracing that uncertainty in a willful, deliberate fashion.

In a letter to Bea dated August 8, 1957, Mailer reacts to Bea’s description of an earthquake in Mexico City:

| “ | Your letter about the earthquake was fascinating, and as a matter of fact made it real to me. All the newspaper accounts here by American journalists in Mexico mentioned how terrifying it was, but no one explained why. Somehow, I got the idea from your account, As I read it, I half wished I had been there, because somehow it seems to me that experiences like that are very valuable—if you really think you’re going to be dead in a minute or so, it must be incredible the way one reacts deep inside. | ” |

This genuine reaction to the unexpected, the life-threatening, the traumatic, Mailer would come to call the “existential situation,” and it became the moment or situation that his protagonists either embraced the challenge, and by implication, embraced life—or fell back on the comfortable, neurotic, reasonable reaction to challenge. Mailer’s successful protagonists rise to the challenge, and even if they fail, they live life to the fullest—at least until the next crisis.

OK, I had too much to eat for lunch. I’ve gone through three boxes today, so I’m calling it.