November 6, 2024

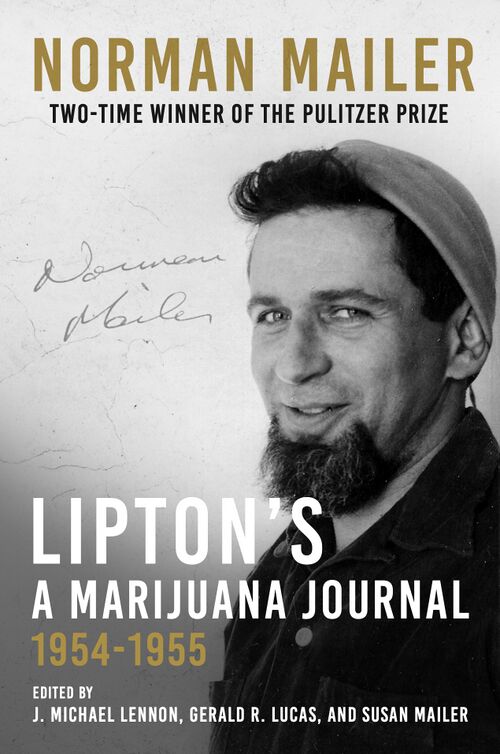

Portrait of the Writer as a Young Man: Norman Mailer’s Lipton’s

I’m pleased to present Lipton’s: A Marijuana Journal, an intimate window into Norman Mailer in the mid-1950s. This journal captures a pivotal moment in his career, as Mailer struggled with the paradox of early success and subsequent hardship. He had experienced meteoric fame with The Naked and the Dead (1948), a war novel that not only received acclaim but also positioned him as a bold new voice in American literature. However, the years following this triumph were marked by doubt and frustration.

For those who may not be familiar with Mailer, here’s a bit of background. Norman Mailer was one of the most influential and controversial American writers of the 20th century. Born in 1923, Mailer rose to prominence with his debut novel, The Naked and the Dead in 1948, a portrayal of the Pacific theater of World War II that brought him instant fame at the age of twenty-five. Often described as both a novelist and a public intellectual, Mailer became known not only for his literary innovations but also for his provocative opinions on politics, culture, and morality. Over his career, he authored a wide range of works—including novels, essays, and nonfiction—that pushed boundaries and tackled issues such as war, existentialism, American identity, and the nature of power. His writing was characterized by its bold style and intrepid engagement with difficult subjects. In the 1950s, however, Mailer found himself in a precarious position, questioning his own literary future and grappling with the direction of his work. This uncertainty and self-doubt are powerfully documented in Lipton’s Journal, which we’ll explore today.

Mailer’s second novel, Barbary Shore (1951), was dismissed harshly, with Time magazine calling it “tasteless, graceless, and paceless”—a review Mailer found deeply wounding and never forgot.[1] The negative reception of Barbary Shore struck Mailer at the core of his identity as a writer, instilling a fear that perhaps his earlier success was a fluke.

His sense of imposterhood was further compounded by Rinehart & Company’s ultimate rejection of The Deer Park, his third novel. He had hoped The Deer Park would redeem him and solidify his reputation as a serious writer; thus, the setback felt devastating, even like a betrayal. Initially, Mailer had made minor concessions to satisfy Rinehart, agreeing to alter a few words in a scene depicting a sexual encounter. But, after some reflection, Mailer reversed course, feeling that compromising would betray his artistic integrity. This defiance led Stanley Rinehart to cancel the book’s release, just three months before it was set to hit the shelves. Rinehart’s decision fueled Mailer’s distrust of publishers and contributed to his developing self-conception as an “outsider” in American letters—a “psychic outlaw” standing in defiance of a society he saw as both prudish and conformist.[2]

This experience intensified his disillusionment, convincing him that the publishing industry was no longer the “gentleman’s occupation” he had once imagined. Instead, he saw it as a business that valued profit and conformity over artistic innovation and free expression. The period Mailer spent struggling to publish The Deer Park ultimately fueled the rebellious, anti-establishment posture he would take up in his writing and public life from the late 1950s onward.

Overcoming Artistic and Personal Struggles

It was amid these professional disappointments that Mailer began Lipton’s Journal in the winter of 1954–55. He used this journal as a form of personal therapy, a space where he could engage in what he called psychoanalytic self-examination, inspired in part by his friend, psychologist Robert Lindner. Mailer saw this journal as a place to work through the immense personal and philosophical pressures he faced while attempting to rediscover and redefine his voice as an artist.

Mailer’s disillusionment fed into his work on Lipton’s Journal, where he explored his frustrations with a society that he saw as stifling individual creativity.

| “ | 142. Most celebrities are people who have had talent or genius in some direction, and terrified of where it might lead them, for genius is always pitted against the world, they have cashed in their talent or genius for the rewards of the world. He “sold out” has deep meaning. It doesn’t mean he sold himself as a slave—although that too is true—it means he or she has sold their substance.[3] | ” |

| “ | 144. Anyone reading these notes would exclaim at my paranoia which rides through these notes on a wave. Three cheers for my paranoia. It is the true measure in every man of great sensitivity—one’s sensitivity to the wrath and retribution of society if one attempts to change it because one knows it is false, and does not suit the need of one’s soul. Society’s great lie is that man is evil and society protects men from one another’s evil. All evil is created by society, and man is good.[3] | ” |

The Role of Marijuana in Self-Exploration

During the period Mailer wrote Lipton’s, marijuana—called “tea” or Lipton’s—became a tool for intense self-examination, allowing him to access what he called his “instinctual self.”[2] Mailer believed that marijuana liberated him from his “societal self” and freed him from what he saw as the conventional, middle-class identity that stifled his creativity. He saw the drug as a way to suppress the “despised image” of himself—the “sweet clumsy anxious to please Middle-class Jewish boy”[4]—and instead nurture what he called the “psychic outlaw” persona he sought to develop.

Mailer’s process was meticulous, often smoking in the afternoons and especially on weekends, as he found that marijuana opened up a mental space for creativity, contemplation, and radical ideas. He felt that the drug was both a means and an end, enhancing everything from his writing and philosophical musings to his appreciation of jazz and even his physical strength. Under its influence, Mailer was able to engage in what he termed “a journey into myself,”[2] where he analyzed complex emotions and attempted to overcome internal inhibitions.

The effects of marijuana were, in Mailer’s view, largely positive, at least initially. It became his “secret weapon” during a period when he felt vulnerable and directionless. In some entries, he expresses a renewed sense of ambition and clarity, claiming that marijuana allowed him to tap into a deeper layer of consciousness that ordinary perception and reasoning could not reach. His reflections often took on the quality of intense self-affirmation, as he declared his goal to “attempt to be a genius”[5] and align himself with writers he admired, such as Dostoyevsky and Hemingway.

| “ | 2. Lipton’s seems to open one to one’s unconscious. Perhaps its brothers do too. Last night, for an experiment, I tried an overhead press with the 45 lb. barbell. I did it seventeen times, double what I normally do, and while I could probably do as much without Lipton’s, I felt very little strain, and no stiffness this morning. Undoubtedly, our latent strength is far greater than our actual, and we become tired or drained because of anxiety. This would account for the super-human strength people exhibit in time of necessity. It is always there, but it takes the threat of death or something which is its psychological equivalent to quiet the anxiety and allow the full strength to appear. Perhaps this is why animals are always so strong for their size—their latent strength is always present.[6] | ” |

Yet, marijuana’s effects were not without drawbacks. Mailer’s use of the drug was often intense, compounded by other substances like Seconal (a barbiturate), alcohol, and caffeine. In one of his most vivid entries, dated March 4, 1955, Mailer describes a terrifying vision of a “divided, vertiginous universe,” during which he felt himself teetering on the brink of insanity. He later confessed that the experience left him “smack on the edge of insanity,” understanding that the drug-induced exploration of the mind came with serious risks, including the potential for madness or self-destruction.

| “ | 707. Also I have been going through terrifying inner experiences. Last Friday night when I took Lipton’s I was already in a state of super-excitation which means intense muscular tension for me. When the Lipton’s hit, and it hit with a great jolt, it was my first in a week, I felt as if every one of my nerves were jumping free. The amount of thought which was released was fantastic. I had nothing less than a vision of the universe which it would take me forever to explain. I also knew that I was smack on the edge of insanity, that I was wandering through all the mountain craters of schizophrenia. I knew I could come back, I was like an explorer who still had a life-line out of the caverns, but I understood also that it would not be all that difficult to cut the life line.[7] | ” |

This complex relationship with marijuana highlights both Mailer’s desire to push the boundaries of his psyche and the dangers inherent in this approach. His journal reveals a pattern of oscillation between exhilaration and terror, an emblem of his belief that the path to true genius was fraught with peril.

Mailer’s use of marijuana, then, can be seen as both an act of rebellion against societal norms and an effort to dismantle his own limitations as an artist. These experiences paved the way for his later, more public explorations of the “psychic outlaw” persona, which he fully embraces in The White Negro and other works.

Major Themes in Lipton’s

Struggles of the Artist in Society

One of Mailer’s recurring themes in Lipton’s is the artist’s role within an unaccommodating society that suppresses creativity and individuality. He critiques society’s demand for conformity, which he views as stifling to the artistic and intellectual spirit. For Mailer, true artistry often places one at odds with social norms, leading to a life of tension and rebellion.

| “ | 223. Homeostasis and sociostasis. I am going to postulate that here is not only homeostasis (which is the most healthy act possible at any moment for the soul), but there is sociostasis which is the health of society so that like people, but acting in the reverse direction, there is a sociostatic element in man placed there by society which resists and wars and retreats against the inroads of homeostasis which is the personal healthy rebellious and soulful expression of man. In the course of a human’s life the child is born all homeostatic (unless the mother has communicated sociostatic components to the embryo) but generally the years of childhood are years in which the homeostatic principle or life-force is blocked, contained, damned, and even destroyed by the creation of sociostatic elements—the child is partially turned into someone who will serve the purposes of society. The essential animal-soul life is contained, forced underground, denied. But as people get older, there is this great tendency for the homeostatic principle to assert itself—middle-aged people kicking over the traces. Depression is the symptom of trench warfare between homeostasis and sociostasis. War in that sense is not the health of the state (Randolph Bourne) but rather is the desperate expression of sociostasis. Society chooses a terrible alternative, but it is the best alternative open to it, given the worse alternative of society disappearing (from its point of view of course, not mine).[8] | ” |

The Artist’s Inner Conflict: Saint vs. Psychopath

Mailer frequently characterizes the artist as existing between two extremes: the saint, who withdraws from society to seek a higher truth, and the psychopath, who challenges societal values without restraint. This duality reflects Mailer’s belief that the artist must resist conventional morality to find authentic expression, while also grappling with internal conflicts and desires.

| “ | 31. The saint and the psychopath are twins. Each are alone; each are honest or rather cannot bear dishonesty. The saint looks for truth in the immaterial world; the psychopath in the world. If the psychopath kills a man because they have quarreled for ten seconds over who was first in line to go through the subway turnstile, it is not so much because he is uncontrollable as because he cannot bear the absolute insanity and indignity of two men quarreling over so insignificant a thing. The saint seeks to lead people away from the world; the psychopath wishes to destroy the world; each has a vision of something else. The saint is aware of how insignificant is the fiction of each envelope, each “individual” who is part of the whole; the psychopath, less far along the route, merely feels that he is no one person, but becomes this person or that person, slipping from skin to skin as the real world presents new situations to him. No wonder that I who at bottom am both can control them only by the apparently silly compromise of an over-friendly anxious boyish, Jewish intellectual—“seductive” and inhibited by turns.[9] | ” |

Existential Reflections on Mortality, Love, and the Self

Mailer explores existential themes in Lipton’s, including the nature of death, love, and the self. For him, these concepts are intertwined with society’s pressure to conform and repress, and he views genuine self-knowledge as involving both love and confrontation with mortality.

| “ | 16. If there is that other world, that sub-stratum of “reality” which one has the impression of “tuning-in” on, perhaps love, the sexual act, the unconscious itself, are all entrances into that reality. Our tendency is for all mankind to join as brothers, but most can approach that only by loving one or a few.[10] | ” |

| “ | 45. There is no death-instinct. There is only anger, and we are not born with anger, not unless the mother is capable of communicating her anger to the embryo. What we think of as the death-instinct, which is applied almost always to the act which seems completely irrational and purposeless, is actually the anger of the soul at being forced to travel the tortured contradictory roads of the social world. The meaningless act is never meaningless—its meaning goes too deep. It is the cry of the soul against society, and it has a purpose—only the most irrational cries can appeal to the souls of others. It is the language allowed us. Only the soul can understand their meaning which is why we flee the impulse in ourselves and others, and call it the death-instinct. All words have their echoes, their deep contraries, and what we call the death-instinct is actually the life of the soul, its anger. But to admit it, to face up to it, is the most terrible revolution a human can undergo, for he loses not only all the vanities of his previous thought, his snobberies, his deceptions, but he is likely to lose his friends, his mate, his reputation, and even most probably his ambition.[11] | ” |

The Crisis of Language and Meaning

Mailer is acutely aware of language’s limitations, particularly as a medium for expressing the raw, visceral truths he seeks to convey. He frequently grapples with how words flatten or distort authentic experience, viewing language as both a tool and a barrier.

| “ | 29. No saint can be a teacher. If there is God, and one arrives at Him, one has passed far beyond words, for words which are polar to meaning are the chains of society. To attempt to teach what one has learned is to return to words, to submit oneself to enslavement again, and so for whatever hint one gives of the direction one also adds falsehood upon falsehood. That is why mystical writers write so badly. What they seek to communicate is simply incommunicable, and the distortion into language properly punishes them by banality. What this means is that everyone must reach God alone. Even more difficult is that one must take the trip alone once one has determined to begin it. One cannot read one’s way to Truth, nor talk one’s way, one can only contemplate. The great artists are saints manqué—they return to teach; they are half-way posts; so long as one has not thought at all about becoming a saint they startle one into considering more, into thinking more, possibly feeling more, and so they encourage large renunciations of the world. But once one feels the other universe, there is no longer any help, only confusion if one looks for aid in books or other people. It is not a very human perspective, but perhaps man, somewhere, has lost the right to reach heavens of truth by brotherhood because brotherhood has been so abused, has been enlisted to the service of the world, of society. So one must go alone. Obviously, I never will. I am a teacher and a talker.[12] | ” |

Jazz as a Metaphor for the Artist’s Freedom

For Mailer, jazz symbolizes a raw and improvisational freedom that resonates with the artist’s struggle for authenticity. He admires jazz’s ability to evade societal strictures, viewing it as a model for a life lived in defiance of conformity and as a metaphor for the creative process itself.

| “ | 8. In modern jazz, one feels a key to aesthetics. Because modern jazz consists almost entirely of surprising one’s expectation, and it is in the degree, small or great, with which each successive expectation is startled, that the artistry lies. But modern jazz has risen to share the crisis of modern painting. It is a self-accelerating process for the audience’s expectations are changed almost nightly (that is, the tight critical yeast of the true aficionados) and so questions of “beauty” disappear before the dilemma—last night’s innovation is tomorrow’s banality. What is suggested is a movement across the arts, each of them engaging the other in order to find new startlings of old expectations until the arts blend, possibly in mathematics, the only art where the expectations of expectations of expectations, etc. can approach infinity.[13] | ” |

Toward a Public Persona

By the mid-1950s, Mailer was moving away from traditional narrative fiction and embracing a more polemical, confrontational approach that fused personal philosophy with social critique. Lipton’s served as a testing ground for this new identity, where he experimented with ideas on individualism, rebellion, and the artist’s duty to challenge societal norms. In the journal, Mailer begins to see himself not just as a novelist but as a public figure with a mandate to critique American society. Mailer’s entries in Lipton’s reveal his growing belief that the artist’s role is to critique and destabilize society’s values, a belief that would underpin his future as a public intellectual. His later works position him as an unrelenting critic of complacency and conformity, a figure who embraces the role of provocateur.

| “ | 58. My characters in The Deer Park are called “unsympathetic” by everyone. And how unsympathetic they must be to the liberal pluralist who represents unhappily the best among editors. For after all, none of my characters go to Parent Teacher Meetings; they are not responsible members of the community; they do not debate whether their little good actions will make the world a little better. They are all psychopaths and saints and people torn between the two, and they wrestle for their souls in a most terrible society, and almost always lose them. Certainly, it is a depressing book, but they are not unsympathetic, my characters. They are souls in torment, and The Deer Park is a journey through torment. It would be a better book, a greater book, if the journey were even more terrible.[14] | ” |

By confronting his own struggles and examining the artist’s place in a conformist society, Mailer begins to adopt what he would later term the “psychic outlaw” identity—an intellectual rebel who operates on the fringes of society, challenging its complacency. In this persona, Mailer was not just an observer but an active participant in the battle against homogenizing societal norms. In discussing marijuana’s effect on his perception of time, Mailer uses the experience as a metaphor for transcending societal constraints. This entry reflects his desire to live unbound by conventional norms, a defining trait of his “psychic outlaw” persona:

| “ | 63. The measurement of time is as necessary to society as the vision of space filled and space unfilled is to the soul. So Lipton’s, which destroys the sense of time, also destroys the sense of society and opens the soul.[15] | ” |

Lipton’s stands as a crucial step in Mailer’s journey from an introspective writer grappling with personal and societal dilemmas to a bold public intellectual determined to critique and transform American consciousness. Through his journal, Mailer found the space to confront the limitations of his own identity and artistic practice, experimenting with ideas of rebellion, existential freedom, and the artist’s role in society. The entries reveal his early struggle to define a persona that would allow him to question and resist the dominant social values of his time.

By confronting his inner conflicts and testing the boundaries of social and moral thought, Lipton’s allowed Mailer to craft the intellectual framework for his next works: The White Negro and Advertisements for Myself. In these writings, Mailer’s insights from the journal crystallize into a coherent philosophy of the “psychic outlaw”—a figure committed to challenging society’s complacency and exposing its contradictions. This evolution marked his shift toward a more mature and provocative voice, one that would resonate powerfully through the 1960s and beyond.

Ultimately, Lipton’s is more than just a record of Mailer’s thoughts; it is a formative work in which he began to shape the rebellious and reflective voice that would define his career. It reveals the groundwork for his mature identity as both an artist and a public figure—a writer determined to disrupt, confront, and redefine the cultural norms of America.

References

- ↑ Mailer 2024, p. vii.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Mailer 2024, p. viii.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Mailer 2024, p. 41.

- ↑ Mailer 2024, p. 52.

- ↑ Mailer 2024, p. xi.

- ↑ Mailer 2024, p. 3.

- ↑ Mailer 2024, p. 238.

- ↑ Mailer 2024, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Mailer 2024, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Mailer 2024, p. 7.

- ↑ Mailer 2024, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Mailer 2024, p. 10.

- ↑ Mailer 2024, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Mailer 2024, p. 20.

- ↑ Mailer 2024, p. 22.

Bibliography

- Mailer, Norman (2024). Lennon, J. Michael; Lucas, Gerald R.; Mailer, Susan, eds. Lipton's: A Marijuana Journal, 1954–55. New York: Arcade.