Notes on “Rappaccini’s Daughter”

Poison is the prevalent gothic element in “Rappaccini’s Daughter.” Poison and its connection with beauty and, in the case of Beatrice, goodness and life also supplies ample Hawthorian ambiguity. All of the characters, in one way or another, are poisoned either mentally or physically. This poison, or poisoning, leads to the tale’s other gothicisms, namely isolation, dreams, horror, dread, and death.

Like Victor Frankenstein, Rappaccini is an over reacher who, we are told by Baglioni, “cares infinitely more for science than for mankind.” This statement may be true when applied to “mankind;” however it is evident that Rappaccini cares for “womankind” or at least his daughter if in a somewhat twisted manner. He created a beautiful, though deadly, garden, gave Beatrice her poisonous protection, and poisoned Giovanni for the sake of his daughter’s happiness. Rappaccini’s creation, like that of Frankenstein, is eventually destroyed by his rival Baglioni.

Baglioni first describe Rappaccini as a scientist whose “patients are interesting to him only as subjects for some new experiment,” people whom he would sacrifice for the sake of knowledge. This statement, however, represents Baglioni to a greater extent than it does Rappaccini by the story’s close. Beatrice lays dead after quaffing Baglioni’s “antidote,” the latter gloating over his victory from the window caring not of the death of Beatrice, his manipulation of Giovanni, or Rappaccini’s ultimate fate. Baglioni’s black science has been the true cause of horror and dread.

The romantic-tempered Giovanni is the Byronic hero that occupies his time with Beatrice. He gets caught in the enigma of the situation: the mysterious, black-robed Rappaccini, his beautiful, poisonous daughter, the sinister garden where insects die and fresh flowers untimely wilt; Giovanni loves Beatrice not, being “incapable of such high faith.” Believing himself to be within a dream, Giovanni is also unsure of his true feelings for Beatrice. He wants to rescue the fair maiden from the evil wizard who keeps her prisoner in the poisonous garden, yet he puts his faith in an even more malignant sorcerer and his black science. Ironically, Beatrice has been kept safe and ostensibly happy within the garden under the love of her father her whole life, would it not then follow that only a stronger love could then rescue her. Giovanni, however, is so spiritually weak that he is unable to rescue Beatrice and becomes poisoned himself with only his indignation and faith in Baglioni’s science to prop him up. Hawthorne seems to be stating that humanity relies too heavily, or puts too much faith, upon science and not enough in the spirituality that makes us truly human.

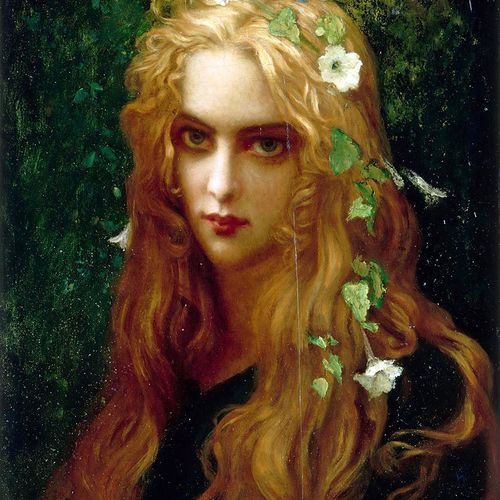

The only victim in “Rappaccini’s Daughter” in the story’s namesake. She is the innocent recipient of her father’s poisonous favors, of Giovanni’s misguided and capricious feelings, and Baglioni’s antidote. She has been isolated her whole life in the garden created by Rappaccini that she wholeheartedly falls in love with the Byronic Giovanni only to have her goodness and beauty smote by a fiend’s antidote. Her final words ring true: “Oh, was there not, from the first, more poison in thy nature than in mine?” Paradoxically, Hawthorne states that “the poison had been life, so the powerful antidote was death.” This paradox is apropos for Beatrice’s physical life had been a paradox of beauty mixed with poison albeit the poison never incriminated her spiritual goodness. Beatrice, innocent and loving, begins her new life by the story’s close, while the scientists and their pawn continue their dread existence without the beauty of Rappaccini’s Daughter.