More actions

Posted. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

{{2002|state=expanded}} | {{2002|state=expanded}} | ||

[[Category:06/2002]] | [[Category:06/2002]] | ||

[[Category:Film]] | [[Category:Film]] | ||

Revision as of 18:47, 17 January 2020

Sweetness Follows...

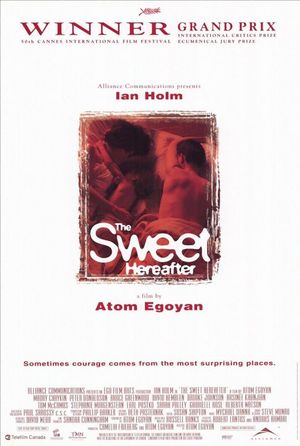

Last night I watched Atom Egoyan’s The Sweet Hereafter again. This beautifully made film concerns itself with the responsibility of parents to their children and to each other. Using the fairy tale “The Pied Piper of Hamlin” as a parallel for the action in the film, Egoyan seems to suggest that the parents are somehow to blame for a school bus that loses control and ends up falling through a frozen lake. Around this central incident all other action in the film revolves.

The protagonist is an ambulence-chasing lawyer, Mitchell Stephens, who comes to the small Canadian town in the wake of this tragedy that kills most of the town’s children. He attempts to build a case against anyone who might be to blame by soliciting support from the grieving parents. Attempting to make sense out of his own personal, on-going tragedy, Stephens wants to help these people in the only way he knows how — since he has been unable to help his own drug-addicted daughter, Zoe — by thowing money, or the promise of money, at it.

The film’s haunting scenes are not presented chronologically, but as a series of flashbacks that augment the main action. Through these flashbacks, we see evidence that the people of this small town are not innocent victims, but indulge in their own questionable activities. These activities range from simple infedelity to, in the case of Nicole and Sam Burnell, child molestation. Like the flow of karma, these erring parents — and some that seem innocent enough — pay for their crimes by losing their children. Does there exist some divine retrobution, or was this simply a tragic and random occurance? The use of the Pied Piper story suggests some greater force at work that places the blame on the erring parents of the town.

Not immune from this karmic flow, Stephens attempts to deal with his own daughter’s drug addiction. Exasperated and almost at his patience’s end, he receives phone call after phone call from Zoe who seems only to want to torture him. Yet, the irony seems to stem from a narrative told by Stephens about Zoe as a child. The latter is ostensibly bitten by an insect, and Stephens is prepared to give her an emergency tracheotomy if her throat closes on the way to the hospital. During his narration he says that he didn’t have to go as far as he was prepared to go, but while we seem to be able to psyche ourselves up for the emergencies in life, it’s our quotidian lives that seem to be our downfalls. How do we fail our children. Do we deserve to have them seeing the we are ourselves flawed and weak?

The Sweet Hereafter poses these questions by attempting to figure out why the bus crashed. Ultimately, all are unanswerable: like Toni Morrison says, the why is too difficult, we have to console ourselves with the how. The how is presented masterfully by Egoyan in a film that haunts us like poetic guilt.