m (Fixed typo.) |

m (Tweaks.) |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | {{DISPLAYTITLE:<span style="font-size:22px; color:#B2BABB;">{{BASEPAGENAME}}/</span>{{SUBPAGENAME}}}} | ||

{{Large|The Climactic Showdown}} __NOTOC__ | |||

{{dc|B}}{{start|ook 22, a pivotal and thrilling section}} of the ''Odyssey'', marks the climactic showdown between Odysseus and the suitors. As we explore this intense and dramatic episode, we will uncover the layers of symbolism, themes, and literary techniques employed by Homer to captivate his audience and convey profound messages about justice, heroism, and the triumph of the rightful king. | |||

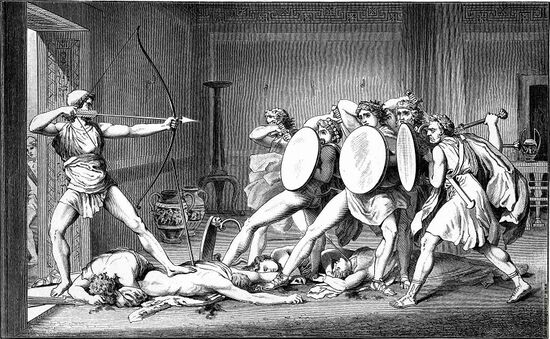

[[File:Thomas Degeorge Ulysse.jpg|thumb|''Odysseus and Telemachus kill the Suitors'', Thomas Degeorge, 1812.]] | [[File:Thomas Degeorge Ulysse.jpg|thumb|550px|''Odysseus and Telemachus kill the Suitors'', Thomas Degeorge, 1812.]] | ||

Book 22 of the ''Odyssey'' takes us to the heart of the action, where Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, unleashes his long-awaited vengeance upon the suitors who have abused his hospitality and sought to usurp his kingdom. The traitorous suitors finally meet their ultimate punishment for their disrespect, greed, and violation of the sacred bonds of hospitality. Their deaths serve as a symbolic representation of divine justice and the consequences of their actions. This climactic moment is a culmination of years of suffering and perseverance for our hero, as well as a test of his wit, strength, and strategic thinking. Through a close reading of the text, we will uncover the intricate web of themes present in Book 22, such as loyalty, honor, vengeance, and the consequences of arrogance. We will discuss the impact of this pivotal moment on the overall narrative arc of the ''Odyssey'' and its significance in showcasing Odysseus' growth as a hero. | |||

As we embark on this chapter, I encourage you to engage actively with the text, analyzing the vivid imagery, the poetic language, and the narrative choices made by Homer. By exploring the depths of Book 22, we will gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of the human condition, the power of justice, and the triumph of the hero against formidable odds. | |||

===Summary=== | |||

Book 22 begins with Odysseus skillfully stringing his great bow, a task that none of the suitors can accomplish. This act symbolizes his rightful claim to the throne and his superior strength and skill. With his bow in hand, Odysseus takes aim and begins to shoot down the suitors one by one, with the help of his loyal son Telemachus and a few trusted allies. | |||

Panic ensues among the suitors as they realize the beggar they had dismissed is, in fact, the legendary hero they feared. Their arrogance crumbles in the face of Odysseus’ righteous fury. Their pleas for mercy fall on deaf ears as Odysseus dispenses swift and brutal justice. The battle intensifies, and the halls of Odysseus’ palace become a battleground. The suitors fight desperately but are no match for the strength, skill, and strategic mind of Odysseus. One by one, they meet their fates, paying the price for their disrespect and arrogance. | |||

As the battle subsides and the suitors lie defeated, Odysseus, with the help of Telemachus, begins the process of cleansing the palace of its impurities. They remove the bodies and clean the bloodstains, symbolically purifying the space that had been desecrated by the suitors’ misconduct. | |||

===Characters=== | |||

In Book 22 of the ''Odyssey'', a several characters come to the forefront, each driven by distinct motivations and carrying out actions that shape the narrative and embody symbolic significance. | |||

At the center of it all is '''Odysseus''', the courageous and cunning protagonist. His motivations lie in reclaiming his kingdom, punishing those who have disrespected him, and restoring order and justice to his household. Through his ability to string the bow, Odysseus demonstrates his strength, strategic thinking, and rightful claim to the throne. His actions symbolize the triumph of the true king, the dire consequences of arrogance, and the power of justice. | |||

For Odysseus, the stakes have never been higher as he confronts the suitors who have invaded his home, disrespected his household, and sought to claim his kingdom and wife. As he reveals his true identity and asserts his authority, Odysseus experiences a mix of emotions. There is a sense of righteous anger and indignation fueled by years of longing for his home and family. The desire for vengeance and justice drives him, yet beneath this resolve lies a layer of vulnerability and uncertainty. Odysseus has been through immense trials and faces the daunting task of reclaiming his kingdom. His psychological state is a delicate balance between determination and the fear of the unknown. | |||

Odysseus’ internal struggles mirror the challenges he has faced throughout his journey, emphasizing his growth as a character and his ability to overcome adversity. | |||

'''Telemachus''', Odysseus’ son, emerges as a key figure in Book 22. His motivations revolve around supporting his father, protecting the honor of their household, and aiding in the restoration of order. Through his growth from a timid youth to a confident and capable young man, Telemachus exemplifies the passing of the heroic legacy from one generation to the next. His actions reinforce the themes of loyalty, filial duty, and the journey to maturity. | |||

{{ | The '''suitors''', led by Antinous and Eurymachus, represent the antagonistic force in the narrative. Their motivations are driven by their greed for power, wealth, and Penelope’s hand in marriage. Their actions are characterized by their disrespect towards Odysseus’ home, their excessive consumption of resources, and their mistreatment of his loyal servants. The suitors symbolize the consequences of hubris and the disruption of Odysseus’ patriarchal order. Their ultimate defeat at the hands of Odysseus shows the triumph of justice and the punishment for their treachery. | ||

The suitors are finally faced with imminent danger and the realization that their actions have consequences. As they witness Odysseus stringing the bow and executing their comrades, a collective sense of fear and panic engulfs them. Their bravado and arrogance crumble, giving way to desperation and regret. They grapple with the sudden realization that they will face retribution for their transgressions. The psychological dimensions of the suitors encompass remorse, self-preservation, and the gnawing fear of impending doom. The suitors’ psychological turmoil highlights the consequences of their excessive pride and lack of respect for divine and human order. | |||

In addition to these key characters, other notable figures contribute to book 22. The disloyal maids, Melanthius the goatherd, and the loyal swineherd Eumaeus and cowherd Philoetius each play a role in the unfolding events. The 12 '''disloyal maids'''’ motivations stem from their alliance with the suitors and their disregard for the hospitality of the household. Their actions result in their eventual punishment by Telemachus. '''Melanthius''', driven by his loyalty to the suitors, aids in their malicious endeavors, but his actions are met with a brutal fate. On the other hand, '''Eumaeus''' and '''Philoetius''' represent loyalty and integrity. Their motivations lie in their unwavering dedication to Odysseus and their role in protecting his interests. | |||

===The Bow=== | |||

The bow of Odysseus holds significant symbolic significance within the narrative of the ''Odyssey''. As an object of power and authority, the bow becomes a focal point that tests Odysseus’ identity, showcases his skill and strength, and serves as a catalyst for the ultimate triumph of justice. | |||

[[File:568-Odysseus-toetet-die-Freier-q32-1595x983.jpg|thumb|550px]] | |||

The bow represents the rightful authority of Odysseus as the king of Ithaca, symbolizes his claim to the throne, and his ability to wield power. Throughout the story, the suitors, who have invaded his home, disrespect his household, and seek to marry his wife Penelope, mock Odysseus’ absence by attempting to string his bow in [[/21|book 21]]. Their failure to do so underscores their illegitimacy and disrespect for the rightful ruler. When Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, reveals his true identity and demands to be given a chance to try stringing the bow, he reaffirms his claim as the true king. His successful stringing of the bow becomes a symbolic declaration of his authority and his readiness to reclaim his kingdom. It serves as a test of his identity and proves his legitimacy in the face of the suitors’ arrogance. | |||

The bow, then, becomes a weapon of justice and retribution. As Odysseus skillfully shoots arrows at the suitors, he delivers punishment for their transgressions and restores order to his household. The bow becomes a symbol of divine retribution and the consequences of their greed and disrespect. Odysseus’ precision and control over the bow reflect his mastery of his own destiny and his ability to exact justice. | |||

The bow also carries a deeper symbolic meaning related to the hero’s journey. In the hands of Odysseus, it represents his development and transformation as a character. Throughout his long and arduous journey, Odysseus faces numerous challenges and tests. The bow serves as a tangible representation of his growth, skill, and resilience. It signifies the culmination of his trials and his ability to overcome obstacles to reach his goal and represents rightful authority, the triumph of justice, and the power of the hero. | |||

===Divine Intervention=== | |||

Divine intervention plays a crucial role in guiding the outcome of the battle. The involvement of the gods reflects their influence and interest in the affairs of mortals, shaping the destiny of the characters and ensuring the triumph of justice. | |||

'''Athena''', Odysseus’ patron goddess, takes an active role in supporting him. She offers guidance and protection, empowering him with strength and agility. Athena’s intervention is crucial in leveling the playing field and ensuring that justice prevails. She helps Odysseus regain his confidence, allowing him to demonstrate his prowess as a warrior. | |||

'''Zeus''', the king of the gods, also plays a significant role in the battle. He symbolizes the ultimate authority and upholds the principles of justice. His presence serves to legitimize the actions taken by Odysseus and reinforce the notion that the suitors’ actions were disrespectful and deserving of punishment. Remember, Zeus himself is the protector of ''xenia'', ultimately punishing those who transgress this divine law. Zeus’ thunderbolt heard at the end of book 21, symbolizing his divine power, signifies the alignment of cosmic forces with Odysseus’ cause. | |||

The role of divine intervention in the battle serves multiple purposes. Firstly, it underscores the epic’s world governed by divine will and intervention. The gods are not passive observers but active participants, enforcing justice and delivering consequences for the actions of mortals. Divine intervention also highlights the contrast between the heroic and the divine realms. Mortals like Odysseus are subject to the whims and interference of the gods, who shape their destinies and influence their actions. The intervention serves as a reminder of the limits of human agency and the supremacy of the divine realm. Also, the gods’ intervention reinforces the overarching theme of justice and retribution. The suitors' actions, driven by their greed and disrespect, have consequences beyond the mortal realm. The gods ensure that justice is served, even if it requires their direct involvement. | |||

===Punishment and Reward=== | |||

The traitorous suitors meet their ultimate punishment for their disrespect, greed, and violation of the sacred bonds of hospitality. Their deaths serve as a symbolic representation of divine justice and the consequences of their actions. | |||

Odysseus, with the help of his loyal allies and the guidance of the gods, executes the suitors one by one. The punishment is swift and brutal, mirroring the severity of their crimes. The suitors, who had abused Odysseus’ hospitality, plotted to steal his kingdom, and vied for his wife’s hand, are now forced to pay the price for their hubris. | |||

The symbolic significance of their punishment lies in the concept of retribution and the restoration of order. The suitors represent a threat to the social and moral fabric of Ithaca. Their actions not only undermine Odysseus’ authority but also disrupt the harmony of the community. By eliminating the suitors, Odysseus restores the rightful order, reaffirming the importance of loyalty, honor, and justice. | |||

The punishment also serves as a powerful message about the consequences of disloyalty and betrayal. The suitors’ fate sends a warning to others who may dare to challenge the rightful authority or betray the bonds of hospitality. It demonstrates the repercussions of selfishness, greed, and disrespect in a world governed by divine justice. The suitors’ punishment also reflects the cyclical nature of fate and the concept of “nemesis,” whereby individuals face the consequences of their actions. The suitors, who have abused their power and squandered the gifts of hospitality, are now confronted with the inevitable outcome of their choices. | |||

Additionally, the punishment of the suitors symbolizes the triumph of Odysseus’ character growth and the reestablishment of his heroic status. Throughout his long journey, Odysseus has developed into a wiser and more compassionate leader. By eliminating the suitors, he asserts his authority and proves his worth as a true hero. The punishment becomes a pivotal moment of catharsis, allowing Odysseus to reclaim his kingdom, restore his marriage, and solidify his place as the rightful ruler of Ithaca. | |||

In addition to the punishment of the suitors, Odysseus also deals with the treacherous maids and the goatherd Melanthius, highlighting the consequences of disloyalty and betrayal. In addition, the swineherd Eumaeus and the cowherd Philoetius demonstrate unwavering loyalty to Odysseus by aiding him in battle and capturing Melanthius. Furthermore, Odysseus spares Phemius, the bard, and one of the heralds, offering insights into his judgment as king. | |||

The perfidy of the maids is considered particularly egregious due to the nature of their betrayal and the breach of trust involved. These maidservants, who were supposed to serve and be loyal to Penelope instead align themselves with the suitors and engage in immoral behavior. Their treachery is deemed particularly egregious due to the extent of their disloyalty, the breach of trust involved, and the violation of social norms and moral principles. Their actions not only contribute to the destabilization of Odysseus’ kingdom but also demonstrate a disregard for the values and customs of the society in which they live. | |||

Odysseus, driven by his need to restore order and seek justice, has them clean up the gore from the slaughter of the suitors, then orders Telemachus to execute them. He does so by stringing them up so they suffocate—not just killing them, but torturing them in the process. Their punishment serves as a stern reminder of the consequences of disloyalty and betrayal. By eliminating them, Odysseus reinforces the importance of loyalty and reveals the severity of their transgressions. | |||

Similarly, Melanthius, the goatherd, is dealt with harshly for his support of the suitors and his involvement in their wicked deeds. He is subjected to a gruesome punishment, including mutilation and death. His fate echoes the consequences faced by those who align themselves with the wrong side and participate in acts of treachery. | |||

In contrast to the traitors, Eumaeus, the loyal swineherd, and Philoetius, the faithful cowherd, exhibit unwavering loyalty to Odysseus. Despite the absence of their lord and the years of hardship they have endured, they remain steadfast in their devotion. Their loyalty is a testament to the enduring bonds of friendship and the unwavering commitment to their rightful king. | |||

As for Phemius, the bard, and one of the heralds, Odysseus spares them from the harsh punishments inflicted upon the suitors and traitorous maidservants. This decision reveals Odysseus’ discernment and mercy. Phemius, although present among the suitors, did not actively participate in their wicked actions. Additionally, as a bard, he holds a role that carries cultural significance and contributes to the preservation of knowledge and storytelling. By sparing him, Odysseus demonstrates a recognition of the importance of art and culture, even in the midst of his quest for justice. The decision to spare one of the heralds is likely driven by a similar rationale. The herald, as a messenger and intermediary, may not have been directly involved in the suitors’ crimes. Moreover, Odysseus understands the value of diplomacy and the need for communication in rebuilding his kingdom and restoring order. | |||

Odysseus’ decision-making process is guided by a sense of justice tempered with mercy. While he seeks retribution for the traitors, he also considers the circumstances and individual involvement of each character. This nuanced approach showcases Odysseus’ growth as a leader and his ability to exercise wisdom and discernment in complex situations. | |||

Overall, the punishments given to the traitorous maidservants and Melanthius underscore the consequences of disloyalty and betrayal. The unwavering loyalty of Eumaeus and Philoetius exemplifies the virtues of fidelity and devotion. Meanwhile, the sparing of Phemius and the herald reflects Odysseus' recognition of the importance of culture, diplomacy, and thoughtful judgment. These actions and choices deepen the narrative and offer insights into the multifaceted nature of justice and loyalty within the "Odyssey." | |||

The punishments meted out in Book 22 carry significant symbolic weight. They represents divine justice, the restoration of order, and the consequences of disloyalty and betrayal. The suitors’ deaths serve as a warning to others and reaffirm the importance of loyalty, honor, and respect. The punishment is also a culmination of Odysseus’ character development and his journey towards reclaiming his rightful place as a hero and king. The symbolic significance of the punishment adds depth and resonance to the overall themes of the epic, resonating with readers as a powerful reminder of the consequences of our actions and the pursuit of justice. | |||

{{Epic|state=expanded}} | |||

[[Category:Homer]] | [[Category:Homer]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:16, 10 May 2023

The Climactic Showdown

Book 22, a pivotal and thrilling section of the Odyssey, marks the climactic showdown between Odysseus and the suitors. As we explore this intense and dramatic episode, we will uncover the layers of symbolism, themes, and literary techniques employed by Homer to captivate his audience and convey profound messages about justice, heroism, and the triumph of the rightful king.

Book 22 of the Odyssey takes us to the heart of the action, where Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, unleashes his long-awaited vengeance upon the suitors who have abused his hospitality and sought to usurp his kingdom. The traitorous suitors finally meet their ultimate punishment for their disrespect, greed, and violation of the sacred bonds of hospitality. Their deaths serve as a symbolic representation of divine justice and the consequences of their actions. This climactic moment is a culmination of years of suffering and perseverance for our hero, as well as a test of his wit, strength, and strategic thinking. Through a close reading of the text, we will uncover the intricate web of themes present in Book 22, such as loyalty, honor, vengeance, and the consequences of arrogance. We will discuss the impact of this pivotal moment on the overall narrative arc of the Odyssey and its significance in showcasing Odysseus' growth as a hero.

As we embark on this chapter, I encourage you to engage actively with the text, analyzing the vivid imagery, the poetic language, and the narrative choices made by Homer. By exploring the depths of Book 22, we will gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of the human condition, the power of justice, and the triumph of the hero against formidable odds.

Summary

Book 22 begins with Odysseus skillfully stringing his great bow, a task that none of the suitors can accomplish. This act symbolizes his rightful claim to the throne and his superior strength and skill. With his bow in hand, Odysseus takes aim and begins to shoot down the suitors one by one, with the help of his loyal son Telemachus and a few trusted allies.

Panic ensues among the suitors as they realize the beggar they had dismissed is, in fact, the legendary hero they feared. Their arrogance crumbles in the face of Odysseus’ righteous fury. Their pleas for mercy fall on deaf ears as Odysseus dispenses swift and brutal justice. The battle intensifies, and the halls of Odysseus’ palace become a battleground. The suitors fight desperately but are no match for the strength, skill, and strategic mind of Odysseus. One by one, they meet their fates, paying the price for their disrespect and arrogance.

As the battle subsides and the suitors lie defeated, Odysseus, with the help of Telemachus, begins the process of cleansing the palace of its impurities. They remove the bodies and clean the bloodstains, symbolically purifying the space that had been desecrated by the suitors’ misconduct.

Characters

In Book 22 of the Odyssey, a several characters come to the forefront, each driven by distinct motivations and carrying out actions that shape the narrative and embody symbolic significance.

At the center of it all is Odysseus, the courageous and cunning protagonist. His motivations lie in reclaiming his kingdom, punishing those who have disrespected him, and restoring order and justice to his household. Through his ability to string the bow, Odysseus demonstrates his strength, strategic thinking, and rightful claim to the throne. His actions symbolize the triumph of the true king, the dire consequences of arrogance, and the power of justice.

For Odysseus, the stakes have never been higher as he confronts the suitors who have invaded his home, disrespected his household, and sought to claim his kingdom and wife. As he reveals his true identity and asserts his authority, Odysseus experiences a mix of emotions. There is a sense of righteous anger and indignation fueled by years of longing for his home and family. The desire for vengeance and justice drives him, yet beneath this resolve lies a layer of vulnerability and uncertainty. Odysseus has been through immense trials and faces the daunting task of reclaiming his kingdom. His psychological state is a delicate balance between determination and the fear of the unknown.

Odysseus’ internal struggles mirror the challenges he has faced throughout his journey, emphasizing his growth as a character and his ability to overcome adversity.

Telemachus, Odysseus’ son, emerges as a key figure in Book 22. His motivations revolve around supporting his father, protecting the honor of their household, and aiding in the restoration of order. Through his growth from a timid youth to a confident and capable young man, Telemachus exemplifies the passing of the heroic legacy from one generation to the next. His actions reinforce the themes of loyalty, filial duty, and the journey to maturity.

The suitors, led by Antinous and Eurymachus, represent the antagonistic force in the narrative. Their motivations are driven by their greed for power, wealth, and Penelope’s hand in marriage. Their actions are characterized by their disrespect towards Odysseus’ home, their excessive consumption of resources, and their mistreatment of his loyal servants. The suitors symbolize the consequences of hubris and the disruption of Odysseus’ patriarchal order. Their ultimate defeat at the hands of Odysseus shows the triumph of justice and the punishment for their treachery.

The suitors are finally faced with imminent danger and the realization that their actions have consequences. As they witness Odysseus stringing the bow and executing their comrades, a collective sense of fear and panic engulfs them. Their bravado and arrogance crumble, giving way to desperation and regret. They grapple with the sudden realization that they will face retribution for their transgressions. The psychological dimensions of the suitors encompass remorse, self-preservation, and the gnawing fear of impending doom. The suitors’ psychological turmoil highlights the consequences of their excessive pride and lack of respect for divine and human order.

In addition to these key characters, other notable figures contribute to book 22. The disloyal maids, Melanthius the goatherd, and the loyal swineherd Eumaeus and cowherd Philoetius each play a role in the unfolding events. The 12 disloyal maids’ motivations stem from their alliance with the suitors and their disregard for the hospitality of the household. Their actions result in their eventual punishment by Telemachus. Melanthius, driven by his loyalty to the suitors, aids in their malicious endeavors, but his actions are met with a brutal fate. On the other hand, Eumaeus and Philoetius represent loyalty and integrity. Their motivations lie in their unwavering dedication to Odysseus and their role in protecting his interests.

The Bow

The bow of Odysseus holds significant symbolic significance within the narrative of the Odyssey. As an object of power and authority, the bow becomes a focal point that tests Odysseus’ identity, showcases his skill and strength, and serves as a catalyst for the ultimate triumph of justice.

The bow represents the rightful authority of Odysseus as the king of Ithaca, symbolizes his claim to the throne, and his ability to wield power. Throughout the story, the suitors, who have invaded his home, disrespect his household, and seek to marry his wife Penelope, mock Odysseus’ absence by attempting to string his bow in book 21. Their failure to do so underscores their illegitimacy and disrespect for the rightful ruler. When Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, reveals his true identity and demands to be given a chance to try stringing the bow, he reaffirms his claim as the true king. His successful stringing of the bow becomes a symbolic declaration of his authority and his readiness to reclaim his kingdom. It serves as a test of his identity and proves his legitimacy in the face of the suitors’ arrogance.

The bow, then, becomes a weapon of justice and retribution. As Odysseus skillfully shoots arrows at the suitors, he delivers punishment for their transgressions and restores order to his household. The bow becomes a symbol of divine retribution and the consequences of their greed and disrespect. Odysseus’ precision and control over the bow reflect his mastery of his own destiny and his ability to exact justice.

The bow also carries a deeper symbolic meaning related to the hero’s journey. In the hands of Odysseus, it represents his development and transformation as a character. Throughout his long and arduous journey, Odysseus faces numerous challenges and tests. The bow serves as a tangible representation of his growth, skill, and resilience. It signifies the culmination of his trials and his ability to overcome obstacles to reach his goal and represents rightful authority, the triumph of justice, and the power of the hero.

Divine Intervention

Divine intervention plays a crucial role in guiding the outcome of the battle. The involvement of the gods reflects their influence and interest in the affairs of mortals, shaping the destiny of the characters and ensuring the triumph of justice.

Athena, Odysseus’ patron goddess, takes an active role in supporting him. She offers guidance and protection, empowering him with strength and agility. Athena’s intervention is crucial in leveling the playing field and ensuring that justice prevails. She helps Odysseus regain his confidence, allowing him to demonstrate his prowess as a warrior.

Zeus, the king of the gods, also plays a significant role in the battle. He symbolizes the ultimate authority and upholds the principles of justice. His presence serves to legitimize the actions taken by Odysseus and reinforce the notion that the suitors’ actions were disrespectful and deserving of punishment. Remember, Zeus himself is the protector of xenia, ultimately punishing those who transgress this divine law. Zeus’ thunderbolt heard at the end of book 21, symbolizing his divine power, signifies the alignment of cosmic forces with Odysseus’ cause.

The role of divine intervention in the battle serves multiple purposes. Firstly, it underscores the epic’s world governed by divine will and intervention. The gods are not passive observers but active participants, enforcing justice and delivering consequences for the actions of mortals. Divine intervention also highlights the contrast between the heroic and the divine realms. Mortals like Odysseus are subject to the whims and interference of the gods, who shape their destinies and influence their actions. The intervention serves as a reminder of the limits of human agency and the supremacy of the divine realm. Also, the gods’ intervention reinforces the overarching theme of justice and retribution. The suitors' actions, driven by their greed and disrespect, have consequences beyond the mortal realm. The gods ensure that justice is served, even if it requires their direct involvement.

Punishment and Reward

The traitorous suitors meet their ultimate punishment for their disrespect, greed, and violation of the sacred bonds of hospitality. Their deaths serve as a symbolic representation of divine justice and the consequences of their actions.

Odysseus, with the help of his loyal allies and the guidance of the gods, executes the suitors one by one. The punishment is swift and brutal, mirroring the severity of their crimes. The suitors, who had abused Odysseus’ hospitality, plotted to steal his kingdom, and vied for his wife’s hand, are now forced to pay the price for their hubris.

The symbolic significance of their punishment lies in the concept of retribution and the restoration of order. The suitors represent a threat to the social and moral fabric of Ithaca. Their actions not only undermine Odysseus’ authority but also disrupt the harmony of the community. By eliminating the suitors, Odysseus restores the rightful order, reaffirming the importance of loyalty, honor, and justice.

The punishment also serves as a powerful message about the consequences of disloyalty and betrayal. The suitors’ fate sends a warning to others who may dare to challenge the rightful authority or betray the bonds of hospitality. It demonstrates the repercussions of selfishness, greed, and disrespect in a world governed by divine justice. The suitors’ punishment also reflects the cyclical nature of fate and the concept of “nemesis,” whereby individuals face the consequences of their actions. The suitors, who have abused their power and squandered the gifts of hospitality, are now confronted with the inevitable outcome of their choices.

Additionally, the punishment of the suitors symbolizes the triumph of Odysseus’ character growth and the reestablishment of his heroic status. Throughout his long journey, Odysseus has developed into a wiser and more compassionate leader. By eliminating the suitors, he asserts his authority and proves his worth as a true hero. The punishment becomes a pivotal moment of catharsis, allowing Odysseus to reclaim his kingdom, restore his marriage, and solidify his place as the rightful ruler of Ithaca.

In addition to the punishment of the suitors, Odysseus also deals with the treacherous maids and the goatherd Melanthius, highlighting the consequences of disloyalty and betrayal. In addition, the swineherd Eumaeus and the cowherd Philoetius demonstrate unwavering loyalty to Odysseus by aiding him in battle and capturing Melanthius. Furthermore, Odysseus spares Phemius, the bard, and one of the heralds, offering insights into his judgment as king.

The perfidy of the maids is considered particularly egregious due to the nature of their betrayal and the breach of trust involved. These maidservants, who were supposed to serve and be loyal to Penelope instead align themselves with the suitors and engage in immoral behavior. Their treachery is deemed particularly egregious due to the extent of their disloyalty, the breach of trust involved, and the violation of social norms and moral principles. Their actions not only contribute to the destabilization of Odysseus’ kingdom but also demonstrate a disregard for the values and customs of the society in which they live. Odysseus, driven by his need to restore order and seek justice, has them clean up the gore from the slaughter of the suitors, then orders Telemachus to execute them. He does so by stringing them up so they suffocate—not just killing them, but torturing them in the process. Their punishment serves as a stern reminder of the consequences of disloyalty and betrayal. By eliminating them, Odysseus reinforces the importance of loyalty and reveals the severity of their transgressions.

Similarly, Melanthius, the goatherd, is dealt with harshly for his support of the suitors and his involvement in their wicked deeds. He is subjected to a gruesome punishment, including mutilation and death. His fate echoes the consequences faced by those who align themselves with the wrong side and participate in acts of treachery.

In contrast to the traitors, Eumaeus, the loyal swineherd, and Philoetius, the faithful cowherd, exhibit unwavering loyalty to Odysseus. Despite the absence of their lord and the years of hardship they have endured, they remain steadfast in their devotion. Their loyalty is a testament to the enduring bonds of friendship and the unwavering commitment to their rightful king.

As for Phemius, the bard, and one of the heralds, Odysseus spares them from the harsh punishments inflicted upon the suitors and traitorous maidservants. This decision reveals Odysseus’ discernment and mercy. Phemius, although present among the suitors, did not actively participate in their wicked actions. Additionally, as a bard, he holds a role that carries cultural significance and contributes to the preservation of knowledge and storytelling. By sparing him, Odysseus demonstrates a recognition of the importance of art and culture, even in the midst of his quest for justice. The decision to spare one of the heralds is likely driven by a similar rationale. The herald, as a messenger and intermediary, may not have been directly involved in the suitors’ crimes. Moreover, Odysseus understands the value of diplomacy and the need for communication in rebuilding his kingdom and restoring order.

Odysseus’ decision-making process is guided by a sense of justice tempered with mercy. While he seeks retribution for the traitors, he also considers the circumstances and individual involvement of each character. This nuanced approach showcases Odysseus’ growth as a leader and his ability to exercise wisdom and discernment in complex situations.

Overall, the punishments given to the traitorous maidservants and Melanthius underscore the consequences of disloyalty and betrayal. The unwavering loyalty of Eumaeus and Philoetius exemplifies the virtues of fidelity and devotion. Meanwhile, the sparing of Phemius and the herald reflects Odysseus' recognition of the importance of culture, diplomacy, and thoughtful judgment. These actions and choices deepen the narrative and offer insights into the multifaceted nature of justice and loyalty within the "Odyssey."

The punishments meted out in Book 22 carry significant symbolic weight. They represents divine justice, the restoration of order, and the consequences of disloyalty and betrayal. The suitors’ deaths serve as a warning to others and reaffirm the importance of loyalty, honor, and respect. The punishment is also a culmination of Odysseus’ character development and his journey towards reclaiming his rightful place as a hero and king. The symbolic significance of the punishment adds depth and resonance to the overall themes of the epic, resonating with readers as a powerful reminder of the consequences of our actions and the pursuit of justice.