Integral Social Media

How I augmented my #MailerClass with social media.

A colleague of mine recently asked me: “isn’t all media—by definition—social?” I see the validity of this question as our world becomes increasingly interconnected through the digital. These days, media actually seem strange to us if they do not have social components—the exact opposite of how we conceptualized and practiced media in the twentieth century. Whereas last century’s media landscape was dominated by the professional, the centralized, and the one-way flow, the new media disrupt and challenge how we express ourselves. While the media landscape might still have the latter characteristics, it seems more defined by the amateurs who decentralize and often reverse the flow.

While “media” has not always been social, our expectations and practices precipitated by the digital continue to have an indelible affect. Because this is the case, the educated must be literate—i.e., have a critical understanding of the use and function of media—in the applications of the digital world.

Many college courses used to be able to ignore the media of the course and focus on the content. That is, by the time students matriculated from the core into major classes, the professor could turn from the mechanics of instruction to the content of instruction. For example, in an upper-level literature class, it could be assumed that students came into class with the functional literacies needed to communicate—like knowledge of essay conventions when writing about literature—we could now concentrate on the more interesting components: the literature itself.

While I’m not ready to throw the essay out of the academy, I do wonder why such effort is still spent in teaching this moribund medium. It does not engage the students; it seems to make their writing more ponderous and academic; and it is a less valued skill in the digital age. Ironically, students still expect the essay as a component of education, so challenging them to look beyond it can sometimes be problematic. Even though the efficacy of the essay printed on dead trees might be in question in a digital age, the spirit of the essay—a container in which knowledge of course content is synthesized and new perspectives are argued—still needs to be preserved.

While I still think that upper-level courses should emphasize course content and often the essay is valuable in evaluating students’ understanding of the content, social media makes a strong addition to the college classroom. My #MailerClass used Twitter, Disqus, and Skype as integral components of the curriculum.

For those who are unfamiliar, Twitter is usually defined as a “microblogging platform”; consider it a hybrid of text messaging and a chat room. Its posts, or “tweets,” are limited to 140 characters, are displayed to a user’s “followers,” and may be read on the web or through any mobile device. Tweets range from reports about a user’s lunch to discussions about quantum physics. Conversations may happen synchronously or asynchronously, and they may be organized under hashtags (#). For example, posts about my Mailer class were labeled with #MailerClass, so they could be found and referenced easily. Each lesson and text had its own hashtag.

The 140-character limit on Twitter requires expressions to be succinct and precise—just the opposite of what academic writing seems to encourage. While Twitter can be criticized for vacuous content, it can also be valuable in getting students to consider rhetoric and composition to form deliberate and exact thoughts. According to Greenhow and Gleason, this encoding and decoding of information represents a new type of literacy: what they call a “Twitteracy.”[1] Digital literacies depend on making informed choices about selecting and using digital platforms and applications for the most efficacious communication. Digital literacies are multimodal, dynamic, participatory, forward-looking.[2] The daily use of Twitter to discuss course materials encourages students to engage key points, report their additional research, and learn a crucial literacy for communicating today. However, the use of any digital tool should be appropriate for the application.

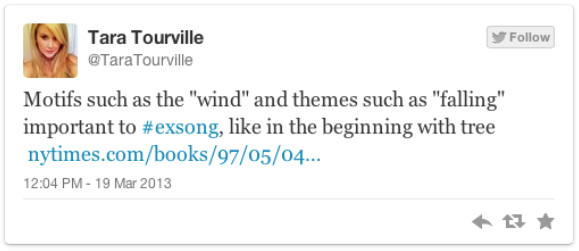

The most literate tweets would be the ones that were thickest—an idea I borrowed from David Silver. Thick tweets make the best use of Twitter by encoding as many layers of information in a single Tweet as possible.[3] For example, Tara’s tweet to the right provides commentary, analysis, and a link to Joan Didion’s review of The Executioner’s Song.

Students are encouraged to make their tweets as thick as they can in order to add to the classes’ understanding of the text under discussion. As students began to use Twitter, I often engaged them to make thin tweets thicker by asking questions that encourage further research or provide support for a supposition. As the students became more proficient with Twitter, my interaction wasn’t as important for maintaining their Twitteracy. We could now use the tool for learning.

The course used Twitter in several ways. Each lesson revolved around a specific text or texts, like The Executioner’s Song (#ExSong). I posted questions for consideration at the beginning of the lesson, so students could choose one or two that interested them. Each required knowledge of the primary text and also encouraged students to look for secondary sources for support. In their exploration, they tweet their findings and analyses using the hashtag, so all are collected, easily referenced, and evaluated.

Often, Twitter would be used in class for asking questions and reporting on group work. For this activity, I would turn on the classroom’s projector, and pull up Tweetchat in a web browser—a service that aggregates tweets based on a single hashtag. As students post their questions and findings, they appear as posted in the Tweetchat window. The class would then come together to discuss some of the points and answer some of the questions, bringing the online discourse into classroom discussions.

Twitter was used in a couple of other ways, especially in the classroom. One use was particularly popular: the lecture liveblog. While I rarely lectured during this semester, when I did, I encouraged the students to capture key ideas in their Tweets, usually assigning a hashtag for the day. After class, they could review their tweets and make additional comments. This exercise, too, allowed me to read through their tweets to see exactly what points they found important, ones that I needed to highlight further, and ideas that were misheard or misunderstood. Similarly, I would often ask students to summarize the top points from the day’s lecture or discussion. This use of Twitter also supplied them with addition ideas to discuss and research.

Twitter is also good for preliminary research and exploration into a topic. One approach is to annotate a text while reading. For example, The Armies of the Night is a historically situated work, replete with references to popular or to political culture of the late sixties. Students were asked to Google items that were unfamiliar, tweet a brief explanation, a textual reference, and a link. These annotation tweets were also collected under a specific hashtag, like #MailerArmies.

I have found Twitter to be an excellent email replacement for two reasons:

- it’s much more convenient, especially if your university is using an archaic email system, and

- it’s more immediate.

Email seems to encourage more formality than is necessary these days—that message carried over from another print medium: letters. Dispensing with salutations, closings, signatures, spam filters, and all the rest of the email quagmire allows for more efficient communication. Since Twitter is more like text messaging, it allows students to send quick questions. Often a question will be answered even more quickly by another student, relieving me of the task. Since the question posted is public, unless a student sends me a private direct message which they can do for more sensitive questions and concerns, then the whole class can see it and benefit from the answer. This sort of interaction, in my experience, binds the class more closely, so it starts to function as a close-knit unit early in the semester. In fact, most students in the class will follow each other and even being using Twitter in a social capacity outside of their class work.

Finally, in order for Twitter to function most efficiently, students need to install it as an application on their devices, so notifications can be sent automatically. One of the best features of Twitter is its immediacy: if a student mentions me in a tweet, my phone lets me know immediately, and vice versa. If Twitter is used as an application, expecting students to check their email—or worse the course management system’s messages—is unnecessary. I have found that even the students who only check their email once a week are very quick to respond on Twitter.

Disqus

Disqus began as a commenting system for blogs, but has grown into its own discussion platform. Whereas Twitter is an informal activity—good for in-class communication and discussion, Disqus might be a good substitute for the essay: a more formal environment where students offer new analyses, synthesize critical ideas, and engage in further discussion about the topics. I emphasize Twitter as a place to explore and gather ideas and Disqus as a place to refine those ideas. Disqus is used like an asynchronous forum attached to my course web site. Discussions are organized in threads, and students may respond to a post or vote it up or down. Threads may be organized chronologically or by popularity. Students may post multimedia to accompany their textual responses, but getting them to link to support is the literacy that I emphasize with this tool.

Disqus has the benefit of a very familiar interface: it is essentially a place for comments under a blog entry. I use Disqus on my course web site, LitMUSE, as a place for student discussions. It has the advantage of being familiar, so students usually possess the technical literacy for its use when they first encounter it. However, like Twitter, I offer them some best practices. I emphasize that these posts are not essays, but like essays, they must have a central point to make, develop that point clearly and logically, and use primary and secondary sources for support. Links are de rigueur, even though initial posts will have awkward remnants of MLA, like works cited lists stuck on the bottom of a post. I offer a brief lesson on basic HTML and using links at the beginning of the semester. I stress that MLA Citation Style is necessary for print documents, but cumbersome and awkward for hypertextual lexia.[a] While there is still no equivalent for the MLA on the web (a good thing?), I find that students take to linking much quicker than they ever do to MLA.

As I mention above, I begin our study of a text or texts with general questions for students to consider as they read and research. These questions are only meant to give them an idea of what they might pay attention to in their reading or viewing and what they could explore further afterward. However, if students have their own questions or areas of interest, I encourage them to pursue those as well.

With Disqus, I place a heavier emphasis on supplying evidence for assertions. This is not a skill unique to the digital age, but perhaps one that needs to be emphasized. While students could address any aspects of Mailer’s texts they found interesting, their suppositions must be supported with evidence from the primary text or links from secondary sources on the web. I would not discourage students from going to the library for actual print books and periodicals, but I choose not to require these types of sources in the digital classroom. That said, the Internet grows as a scholarly resource daily, and many of the campus library’s holdings are available through Google Books. I know many cringe when I say it: but libraries as we have known them are changing because of digital technologies and the behaviors they encourage.

Skype (FaceTime)

Perhaps since it seems so novel, yet reminds us of television, Skype seemed to be one of the class’ favorite activities. One student commented: “Skype interviews were probably the coolest thing I have ever done in a college class.” To me, this is an obvious digital resource, but one I’ve never taken advantage of nor is it one I’ve ever seen any other educator use.

Every classroom on campus is equipped with an Internet-connected computer, a projector, and some sort of audio. I’ve used this equipment many times for presentations, but it took a hint from mobile technologies for me to take it the next step: almost all digital devices today have built-in cameras capable of video. Apple touts its FaceTime as a social application for communicating with friends and family, and they equip every device they make with a camera for doing so. If social services like Twitter and Disqus can be used for education, why not services like Skype and FaceTime.

I decided to call on the Mailer community to help me teach my course. I invited Phil Sipiora to discuss An American Dream, Mike Lennon to provide historical context for The Armies of the Night, and John Buffalo Mailer to talk about The Big Empty and share some stories about his father. Our preparation for these discussions involved reading the primary texts and bringing in questions for the speakers. Both Phil Sipiora and Mike Lennon gave forty-minute presentations after which they took questions. John Buffalo Mailer told some stories and answered questions. Each digital guest spent about an hour with the class, and all precipitated animated classroom and Twitter discussions afterward. One student even took thorough notes of each session and made them available via Google Docs.

On the course exit questionnaire, I asked “what was your favorite activity?” Most students raved about the Skype sessions as a memorable educational experience, for example:

| “ | The Skype interviews were my favorite. They showed another viewpoint that expanded the class’s view of who Mailer is. They also lend to class discussion which was essential for this class. | ” |

Another states:

| “ | My favorite activity was definitely the three times that we had the opportunity to Skype with the Mailer experts: J. Michael Lennon, Philip Sipiora, and of course, John Buffalo Mailer. Their collective first-hand knowledge of the man and novelist that Norman Mailer was proved to be priceless learning information in the classroom. Not only are opportunities like this seldom in the classroom, but all of the experts were so easy to communicate with and learn from. | ” |

And another:

| “ | The skype interviews were outstanding. I could not believe the questions we were able to ask from people who new Norman Mailer the best. It drew me closer to the artist as a person and helped me appreciate his work on a different level. | ” |

Skype proved to be a simple and stimulating activity easily added to the curriculum. All it takes is a community of experts and enthusiasts willing to donate a bit of their time. My class and I both appreciated the efforts of Phil Sipiora, Mike Lennon, and John Buffalo Mailer for making an already good class even better.

Note

Citations

- ↑ Greenhow & Gleason 2012, p. 466.

- ↑ Greenhow & Gleason 2012, pp. 466-67.

- ↑ Silver 2009.

- ↑ Hayles 2001, p. 21.

Works Cited

- Greenhow, Christine; Gleason, Benjamin (2012). "Twitteracy: Tweeting as a New Literacy Practice". The Educational Forum. 76: 463–477. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

- Hayles, N. Katherine (2001). "The Transformation of Narrative and the Materiality of Hypertext". Narrative. 9 (1): 21–39.

- Silver, David (February 25, 2009). "The Difference Between Thin and Thick Tweets". Silver in SF. Retrieved 2020-03-07.