| “ | Still, as a storyteller, I’m fascinated how a person’s sense of consciousness can be so transformed by nothing more magical than listening to words. Mere words. | ” |

| — José Chung | ||

IIn these days of uncertainty — when many of the traditional narratives of our parents, provinces, and priests no longer seem enough to address our contemporary life, where do we turn for answers? When we increasingly feel like aliens, even in a 24/7-connected world, where may we find connections that guide us, but still allow us to walk our individual paths? Is it even possible to find external truths to help us along, or are we all isolated aliens condemned to travel life’s road alone forever? In other words: how do we remain human living in a fragmented postmodern world?

When attempting to define our individual values in a world that would impose its own upon us, we must be ever diligent. We humans seem to be uncomfortable in uncertainty, so many of us accept others’ views of reality without ever seeking our own answers. This can lead to metaphorical cages around our brains, crippling our ability to see possibilities and come to terms with our own sense of reality.

In discussing reader-response criticism, Phillip Sipiora states that “reading literature is a way of ‘ordering reality,’ of seeking stability in a world that may seem to teem with chaos.”[1] Art, in this sense, represents alternative narratives to those that we might have been born into, those spouted by our fathers, or those heard on Fox News every night. Carefully reading cultural texts encourages us to see more than just the comfortable explanations of conventional wisdom, but sometimes when read carelessly, they may lead to their own cages. What this amounts to is a balancing act: how to choose those narratives that give meaning to our life without imprisoning us in the cages of ideology. Three texts, The X-Files’ “José Chung’s ‘From Outer Space,’” William Gibson’s “The Gernsback Continuum,” and Tim Pratt’s “Impossible Dreams,” offer three versions of reality in the intertwined narratives of three different couples.

I Want to Believe

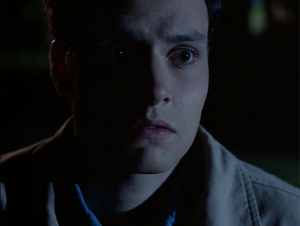

The X-Files’ episode “José Chung’s ‘From Outer Space’” (1996) shatters conventional notions of certainty. The episode begins with a couple—Chrissy and Harold—going on their first date. It’s a familiar scene: a young couple driving to a movie or restaurant in the early evening. Even their conversation is predictable, as Harold — the young romantic—confesses: “Um, I don’t want to scare you, but I think I’m madly in love with you. I mean, you’re all I think about; you’re my whole world.” Chrissy laughs, and lets him down easy: “Harold, I like you a lot, too, but this is our first date. I think that we need some more time to get to know one another.”

With this statement, Harold figuratively attempts to cage Chrissy. His intentions are likely innocent, but his impatient expression of love seems as manipulative as it is ill-timed, attempting to direct the course of Chrissy’s reality to match that of his desires. He wants to impose his will on her—to share his view of the world and make her behave in ways that would please him. This assessment might sound a bit harsh, but Chrissy is about to experience a very real trauma.

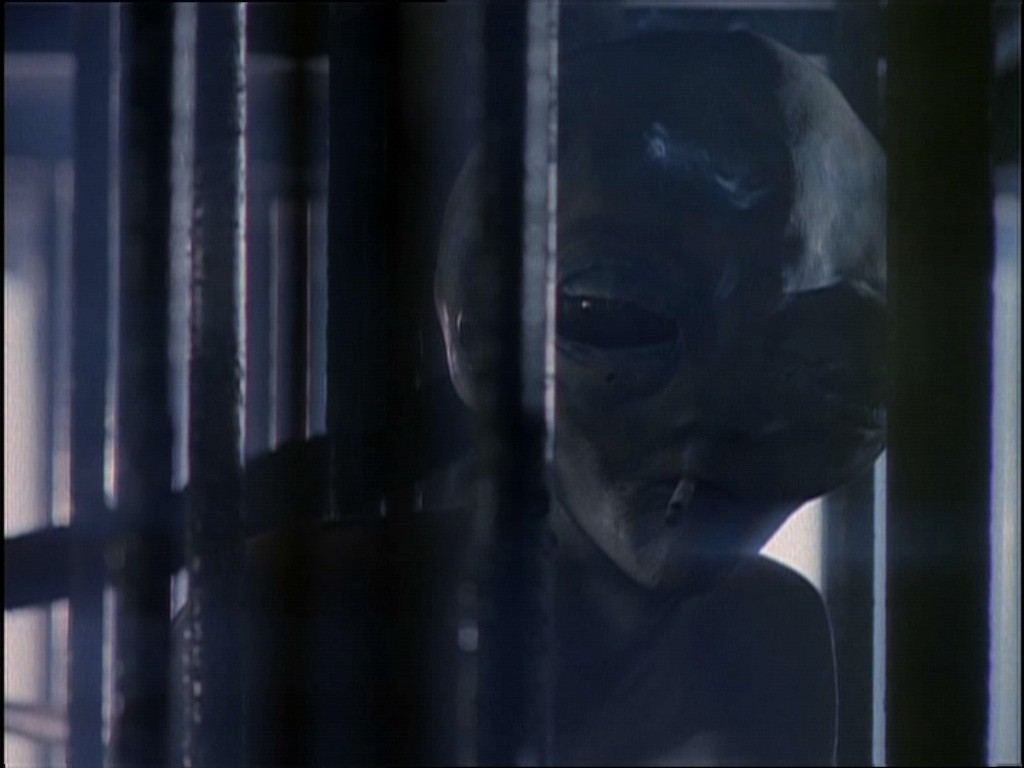

Since this is The X-Files, the familiar scene changes quickly to the inexplicable. The teenagers seem to lose consciousness as a UFO descends and two grey aliens approach the car to abduct the couple. As the greys drag Harold and Chrissy back to their ship, they are interrupted by a third alien that looks more like a mythical beast from Ray Harryhausen’s workshop. One grey looks at another and asks, in a mid-Western, American English: “Jack, what is that thing?” The answer is just an uncertainty:

| “ | How the hell should I know? | ” |

Jack’s answer becomes the theme for this episode, immediately calling into question the series’ assertion that “the truth is out there.” The events of the episode attempt to rationally explain a situation that viewers of The X-Files have become familiar with. The difference, here, is a lack of verisimilitude — an absurd playfulness that seems more like a parody of the show than canonical. In fact, “José Chung” is arguably the funniest episode of a series not known for its humor. This change in tone clues viewers in to the fact that this investigation will be even less conventional.

The rest of “José Chung” shows the various attempts to explain what happened to Harold and Chrissy. While the former seems no worse for wear — perhaps even suspiciously reticent—Chrissy has obviously suffered a trauma. This might be the only verifiable fact of the episode. In “The X-Files Effect,” I argued that in a postmodern world, traditional narratives can no longer encompass trauma—that abductee stories are an alternative way of explaining trauma in a postmodern world. These explanations are the foundation of The X-Files and perhaps lend credence to its 9-year run and permanent place in American popular culture.

So, what happened to Chrissy? It’s never explained, but the end suggests a fairly familiar scenario: that she and Harold engaged in some sort of sexual activity, and it didn’t go well for her. She is found with her clothes on, but backwards and inside-out. She attempts to recall what happened, but everyone she talks to imposes their own explanation of her trauma: alien abduction; military experiments; lavamen orgies; an encounter with men-in-black. However, most seem to overlook the obvious: an admission by Harold to Mulder and Scully that they had “consensual sexual intercourse,” and she was in some way traumatized by an experience she wasn’t ready for.

The end supports this interpretation: Harold still plays the sorrowful young Romeo to Chrissy’s unimpressed Juliet. Under her bedroom widow, he professes his undying love, recalling their conversation in the car at the beginning of the episode. Chrissy has grown up since then, extricating herself from his manipulation by shaking her head and stating disdainfully: “Love. Is that all you men think about?” The voiceover by author José Chung states that Chrissy “has come to believe her alien visitation was a message to improve the condition of her own world, and she has devoted herself to this goal wholeheartedly.” Harold is left brokenhearted and alone, and even if he might be to blame, it’s difficult not to sympathize. Again, Chung’s narration:

Then there are those who care not about extraterrestrials, searching for meaning in other human beings. Rare or lucky are those who find it. For although we may not be alone in the universe, in our own separate ways on this planet, we are all . . . alone.

Despite (or perhaps because of) her PTSD, Chrissy is able to escape the cages that sought to imprison her in their realities. Her experience has given her the ability to take control of her own life and has endowed her with the strength to resist others that might attempt to control her for their own selfish ends. While Harold seems exculpated for any crime, he becomes a pitiable figure by the episode’s end, perhaps himself a prisoner of a narrative stronger than he.

Sinister Fruitiness

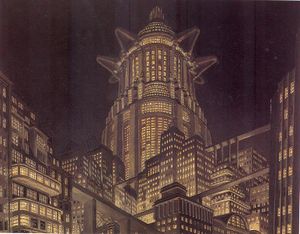

The protagonist in William Gibson’s “The Gernsback Continuum” (1980) finds himself in a similar cage. Hired by a mysterious British woman, Dialta Downes, he thought himself into her vision of America, penetrating a membrane of probability, and goes over “the Edge” to find himself experiencing another reality—one inspired by the “collective yearning of an era” and the “sinister fruitiness” of “the Dream,” or a totalitarian nightmare.[2] If “José Chung” uses satire and the absurd to tell its story, “The Gernsback Continuum” might be be called surreal and phantasmagoric. Both, however, use the accouterments of science fiction to comment on sf narratives and to illustrate the dangers of wandering unwarily into alien continua.

In this case, it’s the unnamed narrator who comes under the sway of Dialta Downes’ desires. She hires the him, an impressionable photographer, to photograph the remaining examples of “American Streamlined Moderne”: an architectural style composed of

those odds and ends of “futuristic” Thirties and Forties architecture you pass daily in American cities without noticing; the movie marquees ribbed to radiate some mysterious energy, the dime stores faced with fluted aluminum, the chrome-tube chairs gathering dust in the lobbies of transient hotels. She saw these things as segments of a dreamworld, abandoned in the uncaring present; she wanted me to photograph them for her.[3]

For Downes, this endangered architecture represents “the Dream” of an unrealized future manifest in the hidden corners of America, slowly being replaced by a new reality.

The narrator turns out to be a successful photographer. Much of his success comes with his ability to “photograph what isn’t there.” “It’s damned hard to do,” he explains, “and consequently a very marketable talent.”[4] He states that he’s pretty good at it, suggesting that he is both creative in his craft and can potentially see things that are not actually present. Later, he states: “I thought myself in Dialta Downes’s America.”[4] He begins to see and photograph the dreamworld along the California coast, until he “penetrated a fine membrane, a membrane of probability. . . .” which pushes him over “the Edge.”[5] At this point, an eversion happens, and what used to be only in books, architecture, and Downes’ enthusiasm begins spilling out into the narrator’s world. These artifacts from another continuum begin to colonize his reality and threaten his sanity.

Downes wants photographic evidence of her vision of a future America that never was, thereby caging the protagonist within that vision. Perhaps she wants him to use his photographic talents to capture (or invent) that dream of a futuropolis. When they first meet, Downes shows the photographer a book containing an illustration of a flying wing liner—a design based on style and ideology, rather than engineering and physics. It made an impression on the protagonist; it was an image that Downes explains represented a dream: “The designers were populists, you see; they were trying to give the public what it wanted. What the public wanted was the future.”[4] Perhaps because this image made such an impression, the first thing that the photographer sees after going over the Edge is a flying wing liner:

And looked up to see a twelve-engined thing like a bloated boomerang, all wing, thrumming its way east with an elephantine grace, so low that I could count the rivets in its dull silver skin, and hear-maybe-the echo of jazz.[6]

He has crossed over into what he comes to call “Downes country”: a continuum that contained “too many fragments of the Dream waiting to snare me.”[7] Even his language reflects the danger of his incarceration. He tries to escape by seeing his friend Merv Kihn—a paranormal investigator — who explains to the narrator that his visions are just “semiotic ghosts”:

It’s simple, plain and country simple: people [. . .] see . . . things. People see these things. Nothing’s there, but people see them anyway. Because they need to, probably. You’ve read Jung, you should know the score. . . . In your case, it’s so obvious: You admit you were thinking about this crackpot architecture, having fantasies. . . . Look, I’m sure you’ve taken your share of drugs, right?[6]

Despite Kihn’s rational and convincing explanation, the photographer is unable to immediately exorcize Downes’ visions from his reality — though there is some credence to Kihn’s observations about his friend, particularly the drugs. Yet, while Kihn makes sense, the narrator keeps experiencing these visions that take on an air of the totalitarian, particularly his next encounter in the Arizona desert. While other explanations present themselves as possibilities for the narrator’s visions, it seems likely that they are allegories out of quantum physics representing the work of totalitarianism. They are Downes’ ideas — or dreams—that threaten to replace the photographer’s own, much like, as I suggest in “Gibson’s Merging Realities,” a virus attacking a host. The implications here begin to manifest themselves in the realities of a parallel American that never was. In essence, here is the power of ideas transforming reality, José Chung’s “mere words” making a very real impact on the receiver. These words come from popular culture, books, authority figures and shape our views of the world, and therefore the realities we inhabit. Yet, some ideas threaten to take over, to block out all other possibilities.

After a final encounter with a Tucson like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and blond Aryan specimens seemingly out of a Nazi propaganda film by Leni Riefenstahl, the narrator makes it back to LA. He escapes Downes county only by narrowing his vision to “a single wavelength of probability”—i.e., by watching bad media and television.[8] In order to dispel the ironic Dream of a perfect nightmare, he had to bring himself back to the imperfect reality of 1980’s America. Ultimately, he passes through Downes country, but not unscathed. It seems her Dream might be with him for a while, perhaps remaining in the recesses of his mind, like American Art Deco’s “raygun emplacements in white stucco” still visible along the byways if you’re looking closely enough.[9]

Movies Mattered

Tim Pratt’s “Impossible Dreams” has another couple at its center, but instead of a threatening story of hegemony, it offers an excitement in possibilities, a connection made through art, and the potential for a happy life. Yet, Pete must first escape a cage of his own creation to make contact with the other. “Impossible Dreams” wears the clothes of science fiction, but ultimately it’s a postmodern love story that unites two unlikely people from universes apart.

“Dreams” uses film as its central operating metaphor. Movies are like their own little universes. Each presents its own world with its own logic. These worlds might seem like the one its viewers inhabit, but the magic of the cinema is that it wisks its audience away to alternate worlds through space and time—each with its own narrative logic. Film’s appeal is visual; its excitement is in the spectacle. It has an immediacy and a universal appeal. I remember seeing Star Wars for the first time in 1977. I was eight-years-old, and George Lucas’ film transported me to a galaxy far, far away—not only for the duration of the film, but also in my daily life. It colored my view of reality, perhaps making it a bit more magical and instilling within me a life-long love of science fiction and adventure. Yet, watching Star Wars thirty years later, I feel the nostalgia it reawakens in me, but its simple plot, cheesy dialog, and silly moral perspective are that of a child’s film. Because I have grown and changed—also influencing what Sipiora calls my “forestructure”—altering my reading of the movie, essentially making it a completely different film today than it was when I first saw it.[10] Logically, I know that Star Wars hasn’t changed—that its text remains constant, but I’m different now, so I read the film differently.

“Dreams” uses a sf premise right out of the Twilight Zone: a video store from an alternate universe appears every night like clockwork, and Pete just happens to be there when it does. Pete is “more comfortable alone in the dark in front of a screen than he was sitting across from a woman at dinner” watches movies as “his main mode of recreation.”[11] He soon realizes that this store is from an alternate reality, as its films were all similar, yet distinct from his reality’s versions. They are like versions made in another continuum, but like a Blu-Ray that contains addicting footage, outtakes, or alternate endings—it’s irresistible candy for a movie aficionado. In his quest to consume all of these films before the store disappears forever, he begins to make a necessary connection with Ally, the store’s clerk.

At first, Pete cares little for impressing Ally, as his primary motivation is watching these alien films. In his obsession, perhaps reflecting his life so far, he almost misses his chance to connect because films had always been more comfortable to Pete than other people. Movies constituted his reality, isolating him from others. Like Harold, in love with love, or Gibson’s photographer, obsessed with Downes’ Dream, Pete’s reality was made up by film fantasy which locks him in a cage or at least colors his reality. For example, when thinking of getting together with Ally, he can’t help but put it in movie terms: “Or maybe he was just trying to turn this miracle into some kind of theatrical romance.”[11] Pete’s cage is one that we might recognize: the danger of spending too much time watching films about life rather than actually living it.

Ironically, it’s through a shared enthusiasm for film that Pete and Ally are able to connect. At one point, she argues against the idea that films are like dreams—that they mattered:

My life doesn’t make a lot of sense sometimes, I’m hungry and lonely and cold, my parents are shit, I can’t afford tuition for next semester, I don’t know what I want to do when I graduate. But when I see a great film, I feel like I understand life a little better, and even not-so-great films help me forget the shitty parts of my life for a couple of hours. Movies taught me to be brave, to be romantic, to stand up for myself, to take care of my friends. I didn’t have church or loving parents, but I had movies, cheap matinees when I cut school, videos after I saved up enough to buy a TV and player of my own. I didn’t have a mentor, but I had Obi-Wan Kenobi, and Jimmy Stewart in It’s a Wonderful Life. Sure, movies can be a way to hide from life, but shit, sometimes you need to hide from life, to see a better life on the screen, to know life can be better than it is, or to see a worse life and realize how good you have it. Movies taught me not to settle for less.[11]

Pete becomes smitten, as if Ally is able to articulate his reality in a way that he had never considered. Film — and arguably literature, music, TV, etc.—help order reality, to dispel the chaos of real life and, as Sipiora points out.[12] But Ally knows that film does not take the place of reality, as she instructs Pete: “And some things don’t have anything to do with movies.”[11] Ally becomes Pete’s reality instructor, figuratively unlocking his self-constructed cage. Her choice to stay with him is a brave one—one of those life chances that we sometimes have to risk for something important. She has more work to do with Pete; he sees their relationship still defined by film. However, she corrects him, pointing to the larger world around them and its possibilities: “We’ve got a lot of everything to do.”[11]

More of Everything

In a world that often presents us with too many possibilities, it’s often easier to retreat into our comfortable continua, shaking our heads, not accepting alternatives (“This is not happening. . .”), or simply throwing up our hands in surrender: “How the hell should I know?” These three narratives illustrate the importance of human interaction and connection, but warn against those who might wish to control our lives or how we often retreat from the world into our own little comfort zones. We walk a fine line between totalitarian order and healthy risk. Either extreme imprisons us, either in the cage of someone else’s view of reality or the fantasy we call home.

Art offers us alternative perspectives that help us grow into thoughtful and critical citizens, yet when obsession is added to the formula, we are in danger of becoming ourselves little dictators. Perhaps Ally’s final words offer us some good advice: don’t become too fixated with any one thing. More of everything might just be the key to happiness. Or at least sanity.

notes

- ↑ Sipiora, Phillip (2002). Reading and Writing about Literature. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 25.

- ↑ William, Gibson (1986). Burning Chrome. New York: Ace. pp. 29, 32, 33.

- ↑ Gibson 1986, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Gibson 1986, p. 26.

- ↑ Gibson 1986, p. 29.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Gibson 1986, p. 28.

- ↑ Gibson 1986, p. 34.

- ↑ Gibson 1986, p. 23.

- ↑ Gibson 1986, p. 27.

- ↑ Sipiora 2022, p. 25.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Pratt, Tim (2006). "Impossible Dreams". Asimov's Science Fiction.

- ↑ Sipiora 2022, p. 26.