Cyberpunk: Difference between revisions

(Upgraded to essay.) |

m (Grlucas moved page December 21, 2013 to Cyberpunk: Upgraded.) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 07:31, 26 February 2020

Cyberpunk

A three-minute, quick-and-dirty primer on cyberpunk.[a]

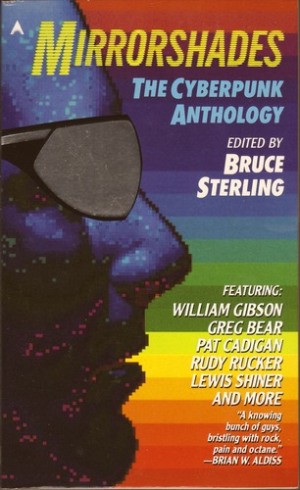

Beginning as a sub genre of science fiction in the early 1980s, cyberpunk became countercultural movement. Because it addressed themes that reflected the reality of the times, it grew to influence all of popular culture, from art to science — both of which can be shocking. Originally know as “The Movement”—a group of writers, including Bruce Sterling, Lewis Shiner, and Rudy Rucker—called for a radical departure from the stagnant state of popular science fiction. Their newsletter called Cheap Truth assumed a punk-like, reactionary voice to announce the forced retirement of the old guard and the arrival of the new literary outlaws.

Cyberpunk exists somewhere in the matrix of Cold War uncertainties, military superpowers, multinational corporations, punk rock, the 24-hour media cycle, and personal electronics. It’s a world where nature has been conquered and humanity’s reach has encompassed the orbit of the moon, where the only frontier left is the infinity of cyberspace and its heroes are the console cowboy, the high-tech geek, and the hypersexual razorgirl. In this world the currency is code—from biology and chemistry, to the matrix—and the hacker with the best program wins. Cyberpunk, then, is a garage-band hack that takes the “cyber” from the personal, digital technologies on the rise around the world, and “punk” for those cultural dissidents who desire to shock and offend.

Cyberpunk’s motto became: “high tech and low life.”

Cyberpunk themes address this contradictory state of the world. With the rise of digital technologies and mass media, never before has the corporation held such power over the masses. Traditional governments have been replaced by the zaibatsu—global corporate conglomerates seeking power and control. These multinational powers are supported by expensive and sophisticated technologies, safe behind physical and digital security in their gleaming high-rises. The heroes of cyberpunk narratives are usually those left over, living at the margins of society where they can see the shiny world of privilege, but are meant to remain outside.

It’s in this gritty reality where the cyberpunk hero operates: using black-market high-tech to challenge and disrupt where they can. The cyberpunk hero combines traditional American myths: they are the rocker / hacker / cowboys who bring together technologies on the street and find new uses for them. These personalized technologies allow a new freedom, movement in the matrix, and body augmentation: the promise of the digital is that information is power, and the one with access has that power, at least until a better hacker comes along.

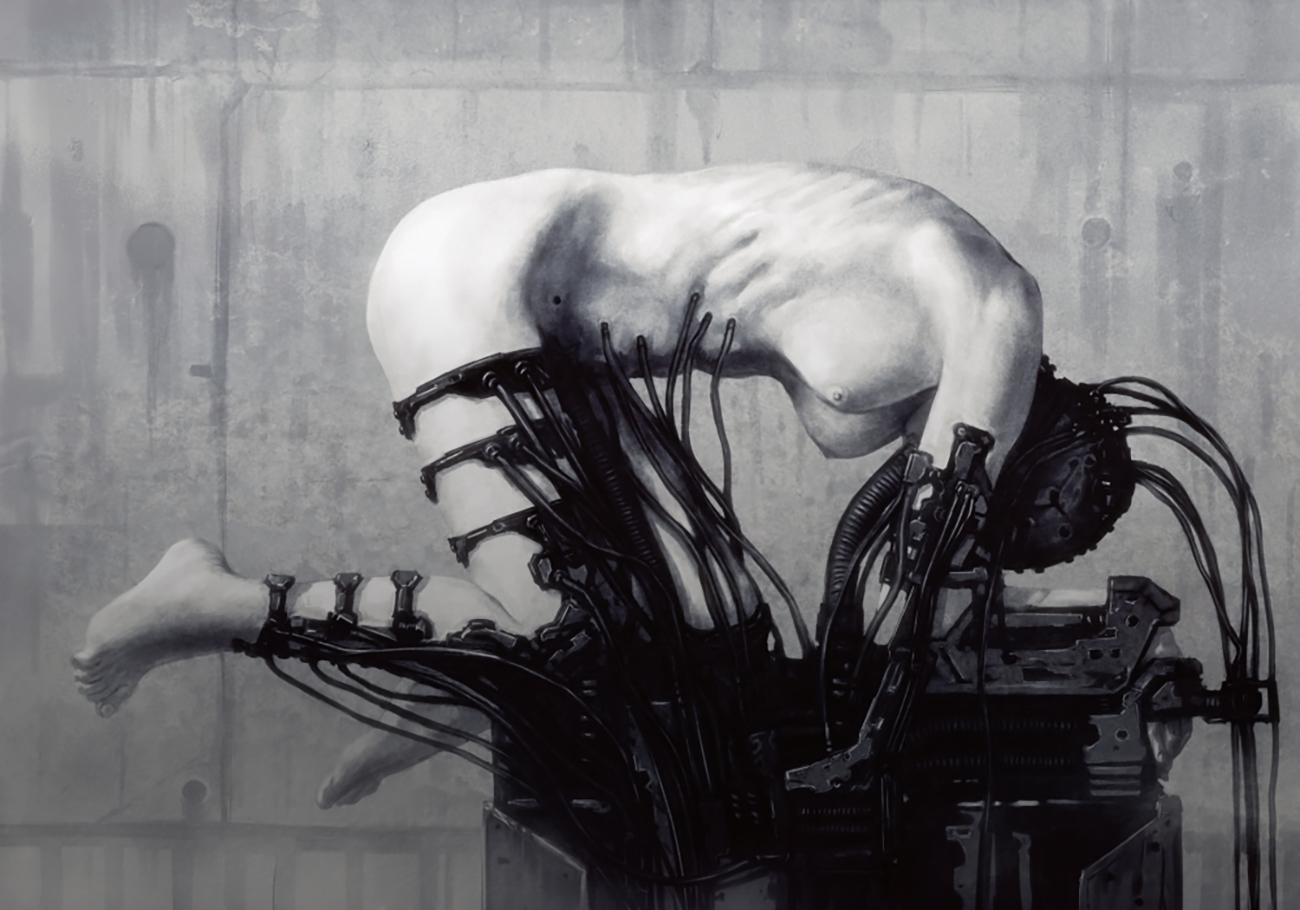

The world of cyberpunk is the one that science made: clean, precise and pulpy, squishy. Technology has replaced nature, and the settings are often post-apocalyptic. Bodies, too, are becoming obsolete as they are pharmaceutically augmented, bio-technically upgraded, and considered meat which imprisons and distracts. Cyberspace—what William Gibson calls the “consensual hallucination”—becomes the preferred reality for daily work and the battleground for control.

Most cyberpunk implicitly asks “who owns the future?” While much of its vision is stark and lawless, in some ways it offers hope for the future that’s more democratic, based on individual aspirations, technical know-how, and street smarts. The cyberpunks offer no utopian future, but one that seems a logical extension of where ours might be headed.

Note

- ↑ December 21, 2013