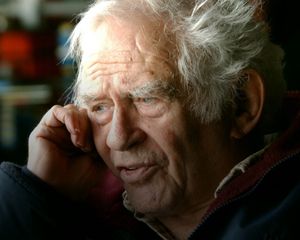

Norman Mailer places the novelist in an ethical and existential position of great responsibility.[a]

| “ | I love the idea of a novel; to me a novel is better than reality. | ” |

| — Norman Mailer[1] | ||

Norman Mailer saw the responsibility of the novelist is a double-edged sword: he must posit an authoritative vision of structure in form and content, yet always be aware that “no authorities exist that have certain knowledge.”[2] This places the novelist in an ethical and existential position of great responsibility. One of Mailer’s chief concerns seems to be with the notion of individual truth and how that truth can lead to creativity, order, and action.

Mailer equates God with the novelist, or vise versa. Like the novelist, Mailer’s conception of the creator is an existential one: God is not all-powerful or all-good in Mailer’s conception, but make mistakes and tries again.[3] God as artist, it seems to Mailer, remains true to his vision and his own creativity, even though occasionally messing up. Like an artist, God evolves with us and “still has an unfulfilled vision and wishes to do more.”[4]

Mailer’s Christ in The Gospel According to the Son is also a metaphor for the novelist: one, Mailer suggests, who does the best that he can under difficult, if not impossible, circumstances.[5] Christ’s voice is that of narrator and novelist, seeking through the “small miracle” of the text to “remain closer to the truth” in his account.[6] He explicitly distances himself from the gospels and the intention of the scribes who seem to have their own agendas. The truth, therefore, is in his vision — one that is subjective and existential, though authoritative. He, like the novelist, seeks to uncover the truth, unlike others who would bury it for their own purposes.

The authority here is not necessarily with an account of factual occurrences, but with the narrative, the struggle for order and identity. These are battles Mailer seemed to fight his whole life, and which kept him close to his vision of God, the ultimate creator and authority. Yet, for Mailer, God was not properly “God,” but a god among many that, like his narrators Christ in Gospel and Mailer in The Armies of the Night, sought “to develop their vision of existence rather than accept visions from other gods opposed to them.”[7] God is not all-power, but trying to do the best he or she can against great odds.

Creation seems to come, then, from narrative, or to paraphrase Mailer’s subtitle for Armies: the novel is history and history is the novel. Less a true “novel” and more of a journalistic-novel hybrid, J. Michael Lennon, in “Norman Mailer: Novelist, Journalist, or Historian?” reminds us that Armies was written during the period of Mailer’s career where he seemed to push the novel beyond its traditional limits — as if to be true to his own growth, the novel could no longer contain the truth that Mailer sought.[8] He seemed to suggest that the narrative order of the novel and the waves of history were connected in extricably and dynamically, that even “facts” become like a fiction, as they seemed to do in Mailer’s work during this period, perhaps most successfully in The Executioner’s Song. Historical facts charged by the authoritative narrative of the novelist become, perhaps, closer to the truth than reality. There is a give and take: life is never as orderly as fiction, though everyday we attempt to impose our fictions upon it. Mailer states:

| “ | I think in fiction, what we want to do is we want to create life. We want to give the readers the feeling that they are participating in the life of the characters they’re reading about. And to the degree that they’re participating in it, they shouldn’t necessarily understand everything that’s going on anymore than we do in life.[9] | ” |

Similarly, Mailer states elsewhere that when the great historian writes, she is also a writer of great fiction.[10] Lennon goes on to conclude that Mailer elevated the novel and the novelist as the true creative spirits, ones that pose difficult questions in order to provoke, to incite, and to contend. Whereas the historian and journalist work with pre-digested facts, intended to answer, to clarify, and to end.[11] Mailer is not writing in an easily understandable prose for the masses, he is challenging readers to rise up to his level; this is not journalism or television — it is literature.[12]

Yet, while the novelist is not limited by the facts of history, perhaps the novel is for a Mailer — or at least the realities of identifiable historicity that remain the touchstones for communication and meaning. Mailer seems to be calling out the fictional nature of all narrative, whether based on fact or imagination, and as Lennon avers, Mailer uses whatever form he needs to “carry the tale forward to the century’s end.”[13] In a way, it’s as if Mailer suspects that the novel is no longer capable of influencing people’s consciousness as it did before World War II.[14] It’s as if the authority of the narrative is linked to history, culture, and the artist’s place in it: the narrative grows with the author and creator. The best novel, then, remains true to the novelist’s vision at the moment of creation. This seems to be a moral imperative with Mailer — an imperative that forced him to push the boundaries of genre.

Another link between history and the novelist is the idea of the novelist as savior. Alfred Kazin sees Mailer as primarily a “moralist” — one who has an “acute sense of national crisis” and a responsibility not to leave this crisis in the hands of the journalists.[15] Mailer’s authority as a novelist attacks what he sees as an American authority that is misplaced and. Mailer plays the social miscreant and his role as the artist, asking questions, getting in the way, and putting himself in the middle of the conflict, both metaphorically and literally.

Armies is a novel of opposition: political, aesthetic, and moral. Mailer’s opposition in Armies holds contempt for the American military-industrial complex and is monolithic symbol in the Pentagon, but at the same time he it also sees as its opponent the mediocrity of the America’s insipid middle class. His revolution in Armies is not just against American leadership, but also those forms that have become too tarnished by quotidian reality. “Opposition” might best describe Mailer’s own aesthetic approach to literature which informed the narrative of his public persona. The best oppositional tool of the time was Mailer’s hybrid “novel,” a genre that might have been pushed and stretched as far as it will go.

Finally, Mailer might have been opposing the novel. After all, it’s older than the Pentagon, and perhaps more ossified. The civil unrest of the sixties demanded political and social change, and maybe The Armies of the Night itself demanded a new literary medium.

Note

- ↑ June 6, 2011.

Citations

- ↑ Lennon 2006, p. 91.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, p. 218.

- ↑ Mailer 2007, pp. 7, 11, 13, 33, ff..

- ↑ Mailer 2007, pp. 35, 22.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, p. 214.

- ↑ Mailer 1997, p. 4.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, p. 215.

- ↑ Lennon 2006, p. 94.

- ↑ Lennon 2006, pp. 95–6.

- ↑ Lennon 2006, p. 96.

- ↑ Lennon 2006, p. 97.

- ↑ Bufithis 1978, p. 90.

- ↑ Lennon 2006, p. 101.

- ↑ Adams 1976, pp. 100-101.

- ↑ Kazin 1968, p. 2.

Works Cited

- Adams, Laura (1976). Existential Battles: The Growth of Norman Mailer. Ohio UP.

- Bufithis, Philip H. (1978). Norman Mailer. Modern Literature Monographs. New York: Frederick Unger.

- Kazin, Alfred (May 5, 1968). "The Trouble He's Seen". The New York Times. Books. Retrieved 2020-02-25.

- Lennon, J. Michael (2006). "Norman Mailer: Novelist, Journalist, or Historian?". Journal of Modern Literature. 30 (1): 91–103.

- Mailer, Norman (1997). The Gospel According to the Son. New York: Random House.

- —; Mailer, John Buffalo (2006). The Big Empty: Dialogues on Politics, Sex, God, Boxing, Morality, Myth, Poker and Bad Conscience in America. New York: Nation Books.

- —; Lennon, J. Michael (2007). On God: An Uncommon Conversation. New York: Random House.