No simple label can describe the Romantic Age, for if anything the artists of this era were individualists. Some were disillusioned by the empty promises of the French Revolution; most were disgusted with the mechanistic society they saw around them in their cities. They seemed to feel that the men before them had been too analytic, too dogmatic, too shackled to rules set up by formidable academies. Now it was time for self-expression, for a new emergence of the individual and his feelings. The following sources point to some of the directions this concern with self took.

The Man of Feeling

The paradoxical Frenchman, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), a writer, musician, and vagabond, was one of the greatest literary influences on the Romantics. In proclaiming the supremacy of the self in his autobiography, The Confessions, he gave rise to the subjective literature characteristic of the period—the lyric poem and the spiritual auto-biography:

I am commencing an undertaking, hitherto without precedent, and which will never find an imitator. I desire to set before my fellows the likeness of a man in all truth of nature, and that man is myself.

Myself alone! I know the feelings of my heart, and I know men. I am not made like any of those I have seen; I venture to believe that I am not made like any of those who are in existence. If I am not better, at least I am different. . . .

I have neither omitted anything bad, nor interpolated anything good. If I have occasionally made use of some immaterial embellishments, this has only been in order to fill a gap caused by lack of memory. I may have assumed the truth of that which I knew might have been true, never of that which I knew to be false. I have shown myself as I was: mean and contemptible, good, high-minded, and sublime, according as I was one or the other. I have unveiled my inmost self even as Thou hast seen it, o Eternal Being. Gather round me the countless host of my fellow men; let them hear my confessions, lament for my unworthiness, and blush for my imperfections. Then let each of them in turn reveal, with the same frankness, the secrets of his heart at the foot of the Throne, and say, if he dare, “I was better than that man!”

I felt before I thought: this is the common lot of humanity. I experienced it more than others. I do not know what I did until I was five or six years old. I do not know how I learned to read. I only remember my earliest reading, and the effect it had upon me; from that time I date my uninterrupted self-consciousness. . . . I had no ideas of things in themselves, although all the feelings of actual life were already known to me. I had conceived nothing, but felt everything. These confused emotions which I felt one after the other, certainly did not warp the reasoning powers which I did not as yet possess; but they shaped them in me of a peculiar stomp, and gave me odd and romantic notions of human life, of which experience and reflection have never been able wholly to cure me.

From Germany, one of the first centers of the Romantic movement, came Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), a poet, critic, dramatist, scientist, and novelist. During Germany’s “Sturm und Drang” (Storm and Stress) literary movement, Romanticism was at its most emotional and sentimental. It was Goethe’s Werther who exemplified one common romantic pose—the sensitive, self-pitying young man who constantly despairs over his misfortunes in life and most especially in love:

August 30

Unhappy man! Aren’t you a fool? Aren’t you deceiving yourself? What sense is there in this raging endless passion? I no longer have prayers except to her; no other form appears to my imagination except hers, and I see everything in the world about me only in relation to her. And this brings me many a happy hour—until I must tear myself away from her again. Oh Wilhelm! The things my heart often urges me to do!—When I have been sitting with her for two or three hours and have feasted on her figure, her manner, the divine expression of her thoughts, and then gradually my senses become tense, a darkness appears before my eyes, I can scarcely hear anything, my throat is constricted as though by the hand of an assassin, and my heart beats wildly trying to relieve my oppressed senses, but only increasing their confusion—Wilhelm, often I don’t know whether I really exist. And at times—when melancholy does not get the upper hand and Lotte permits me the wretched comfort of shedding my tears of anguish on her hand—I must leave her, I must get outside and roam far through the fields; I then find my pleasure in climbing a steep mountain, cutting a path through an untrodden forest, through hedges which tear me, through thorns which rend me. Then I feel a little better. A little . . . Oh, Wilhelm! The solitary dwelling of a cell, the hair shirt, and belt of thorns are the comforts for which my soul yearns. Goodbye; I see no end to this misery but the grave.

November 26

Sometimes I tell myself: Your fate is unique; consider other men fortunate—no one has ever been tormented like this. Then I read some poet of ancient times and I feel as if I were looking into my own heart. I have so much to endure! Ah, have men before me ever been so wretched?

Search for the Lost Past and the Exotic

The same Romantic age which exalted the common man, the child, the forces of nature, also found its subject in the remote and the mysterious. The world of the past, particularly of Ancient Greece and of the Middle Ages, was a prime source for many poems and stories. Yet typically, not even in the splendor of the lost past did the romantic hero find more than fleeting happiness and love:

|

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms, |

René

By: François-René de Chateaubriand

Nevertheless, I set forth all alone and tall of, spirit on the stormy ocean of the world, though I knew neither its safe ports nor its perilous reefs. First I visited peoples who exist no more. I went and sat among the ruins of Rome and Greece, those countries of virile and brilliant memory, where palaces are buried in the dust and royal mausoleums hidden beneath the brambles . . . I meditated on these monuments at every hour and through all the incidents of the day. Sometimes, I watched the same sun which had shone down on the foundation of these cities now setting majestically over their ruins; soon afterwards, the moon rose between crumbling funeral urns into a cloud-less sky, bathing the tombs in pallid light. Often in the faint, dream-wafting rays of that planet, I thought I saw the Spirit of Memory sitting pensive by my side . . . On the mountain peaks of Caledonia, the last bard ever heard in those wildernesses sang me songs which had once consoled a hero in his old age. We were sitting on four stones overgrown with moss; at our feet ran a brook, and in the distance the roebuck strayed among the ruins of a tower, while from the seas the wind whistled in over the waste land of Cona . . . And yet with all my effort what had I learned until then? I had discovered nothing stable among the ancients and nothing beautiful among the moderns. The past and present are imperfect statues—one, quite disfigured, drawn from the ruins of the ages and the other still devoid of its future perfection.

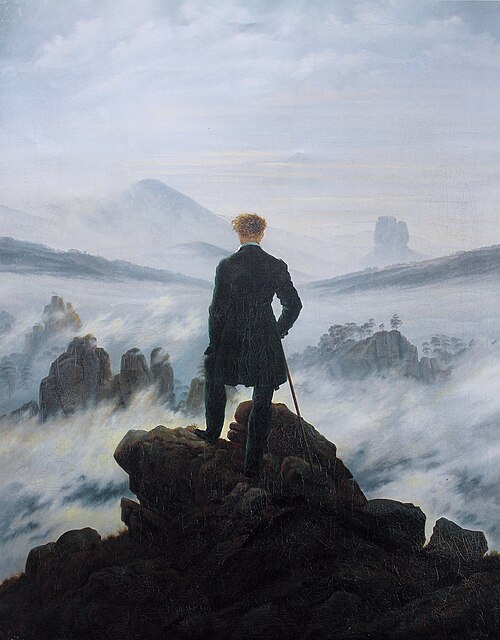

Nature Versus City Life

In Nature, the Romantic artist found the beauty that was lacking in the ugliness of the city—an ugliness which he felt was repugnant not only to man’s sight, but to his soul as well. Yet Nature at her best represents more than simply a serene contrast to the city. She is the mystery that “rolls through all things,” the “still, sad music of humanity,” and in her the poet finds the essence of life and growth:

|

I wander thro’ each charter’d street |

|

Five years have past; five summers, with the length |

The Romantic Manifestos

In an age of technical endeavor, the Romantics called attention to the individual—his feelings, his experiences, his imagination. It is not unusual, then, that poetry would be at the heart of romantic literature. Wordsworth describes poetry as the “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.” But convincing men that the poet’s feelings and creative imagination were “at once the centre and circumference of all knowledge” was not an easy task. The excerpts from Shelley and Wordsworth attempt to define and defend the function of the poet and his poetry against the society described by Thomas Carlyle. While not of a strictly romantic temperament, Carlyle, British historian and social critic, did align himself with the Romantics in lashing out against the materialism and mechanism in society.

Signs of the Times

By: Thomas Carlyle

Were we required to characterize this age of ours by any single epithet, we should be tempted to call it, not an Heroical, Devotional, Philosophical, or Moral Age, but, above all others, the Mechanical Age. It is the Age of Machinery, in every outward and inward sense of that word; the age which, with its whole undivided might, forwards, teaches, and practices the great art of adapting means to ends. . . . Not the external and physical alone is now managed by machinery, but the internal and spiritual also. Here too nothing follows its spontaneous course, nothing is left to be accomplished by old natural methods. Everything has its cunningly devised implements, its preestablished apparatus; it is not done by hand, but by machinery. . . . Instruction, that mysterious communing of Wisdom with Ignorance, is no longer an indefinable tentative process, requiring a study of individual aptitudes, and a perpetual variation of means and methods, to attain the same end; but a secure, universal, straightforward business, to be conducted in the gross, by proper mechanism, with such intellect as comes to hand. . . . In defect of Raphaels, and Angelos, and Mozarts, we have Royal Academies of Painting, Sculpture, Music. . . . These things . . . indicate a mighty change in our whole manner of existence. For the same habit regulates not our modes of action alone, but our modes of thought and feeling. Men are grown mechanical in head and in heart, as well as in hand. They have lost faith in individual endeavor, and in natural force, of any kind.

Preface To Lyrical Ballads

The principal object, then, proposed in these poems was to choose incidents and situations from common life, and to relate or describe them, throughout, as far as was possible in a selection of language really used by men. . . . Humble and rustic life was generally chosen because, in that condition, the essential passions of the heart find a better soil in which they can attain their maturity, are less under restraint, and speak a plainer and more emphatic language; because in that condition of life our elementary feelings coexist in a state of greater simplicity . . . and, lastly, because in that condition the passions of men are incorporated with the beautiful and permanent forms of nature. . . .

What is a poet? To whom does he address himself? And what language is to be expected from him? He is a man speaking to men: a man, it is true, endowed with more lively sensibility, more enthusiasm and tenderness, who has a greater knowledge of human nature, and a more comprehensive soul, than are supposed to be common among mankind; a man pleased with his own passions and volitions, and who rejoices more than other men in the spirit of life that is in him; delighting to contemplate similar volitions and passions as manifested in the goings-on of the universe, and habitually impelled to create them where he does not find them. . . .

Aristotle, I have been told, has said that poetry is the most philosophic of all writing: it is so; its object is truth, not individual and local, but general, and operative; not standing upon external testimony, but carried alive into the heart by passion; truth which is its own testimony. . . . The man of science seeks truth as a remote and unknown benefactor; he cherishes and loves it in his solitude; the poet, singing a song in which all human beings join with him, rejoices in the presence of truth as our visible friend and hourly companion. Poetry is the breath and finer spirit of all knowledge; it is the impassioned expression which is in the countenance of all Science.

A Defense of Poetry

The exertions of Locke, Hume, Gibbon, Voltaire, Rousseau, and their disciples, in favor of depressed and deluded humanity, are entitled to the gratitude of mankind. Yet it is easy to calculate the degree of moral and intellectual improvement which the world would have exhibited, had they never lived. A little more nonsense would have been talked for a century or two; and perhaps a few more men, women, and children burnt as heretics. We might not at this moment have been congratulating each other on the abolition of the inquisition in Spain. But it exceeds all imagination to conceive what would have been the moral condition of the world if neither Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Calderon, Lord Bacon, nor Milton, had ever existed; if Raphael and Michael Angelo had never been born; if the Hebrew poetry had never been translated; if a revival of the study of Greek Literature had never taken place; if no monuments of ancient sculpture had been handed down to us; and if the poetry of the religion of the ancient world had been extinguished together with its belief. The human mind could never, except by the intervention of these excitements, have been awakened to the invention of the grosser sciences, and that application of analytical reasoning to the aberrations of society, which it is now attempted to exalt over the direct expression of the inventive and creative faculty itself.

We have more moral, poetical and historical wisdom than we know how to reduce into practice; we have more scientific and economical knowledge than can be accommodated to the just distribution of the produce which it multiplies. The poetry, in these systems of thought, is concealed by the accumulation of facts and calculating processes. . . . We want the creative faculty to imagine that which we know; we want the generous impulse to act that which we imagine; we want the poetry of life: our calculations have outrun conception; we have eaten more than we can digest. The cultivation of those sciences which have enlarged the limits of the empire of man over the external world, has, for want of the poetical faculty, proportionally circumscribed those of the internal world; and man, having enslaved the elements, remains himself a slave. . . . Poetry is indeed something divine. It is at once the centre and circumference of knowledge; it is that which comprehends all science and that to which all science must be referred. It is at the same time the root and blossom of all other systems of thought. . . . Poets are the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration; the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present; the words which express what they understand not; the trumpets which sing to battle, and feel not what they inspire; the influence which is moved not, but moves. Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.

Bibliography

- Bernbaum, Ernest (1949). Guide Through the Romantic Movement. New York: The Ronald Press Company.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1984). Tennyson, G. B., ed. A Carlyle Reader. New York: Modern Library.

- Chateaubriand, François René de (1966). "René". In Mack, Maynard. The Norton Anthology of World Masterpieces (Fifth Continental ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Co. pp. 1733–1754.

- Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von (1970). The Sufferings of Young Werther. Translated by Steinhauer, Harry. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Hugo, Howard E., ed. (1957). The Portable Romantic Reader. New York: Viking.

- Langbaum, Robert (1957). The Poetry of Experience. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Priestly, J. B. (1960). Literature and Western Man. New York: Harper and Brothers.

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques (1996). The Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. New York: Wordsworth Classics.

- Spencer, Hazleton; Houghton, Walter E.; Barrows, Herbert, eds. (1952). British Literature from Blake to the Present Day. Boston: D. C. Heath and Company.

- Wordsworth, William (1960). The Prelude, Selected Poems and Sonnets. New York: Rinehart.