August 23, 2021: Difference between revisions

From Gerald R. Lucas

(Created entry. More to do.) |

(Additions. More to do.) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Jt}} | {{Jt}} | ||

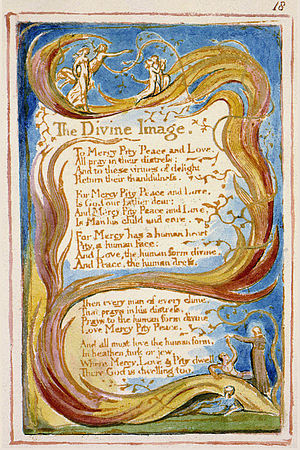

[[File:Songs of Innocence and of Experience, copy AA, 1826 (The Fitzwilliam Museum) object 18 The Divine Image.jpg|thumb]] | [[File:Songs of Innocence and of Experience, copy AA, 1826 (The Fitzwilliam Museum) object 18 The Divine Image.jpg|thumb]] | ||

{{Center|{{Large|The Divine Image}}{{refn|From ''[[w:Songs of Innocence and of Experience#Songs of Innocence|Songs of Innocence]]'', 1789. Compare this poem to its ''contrary'', the “[[Human Abstract]]” from ''Songs of Experience''.}}<br /> | {{Center|{{Large|The Divine Image}}{{refn|From ''[[w:Songs of Innocence and of Experience#Songs of Innocence|Songs of Innocence]]'', 1789. Compare this poem to its ''contrary'', the “[[The Human Abstract]]” from ''Songs of Experience''.<br />{{Sp}}In “A Cradle Song,” Blake dramatizes a mother’s love for her child and writes that “we come to know God by ‘honouring his gifts/In other men{{' "}}; this theme is developed further here ({{harvnb|Tomlinson|1987|p=38}}). The human qualities of “Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love” are esteemed by us, so they would be important in God who, in turn, might bestow them upon the devout, as in the third stanza. Blake wrote “Think of a white cloud as being holy, you cannot love it; but think of a holy man within the cloud, love springs up in your thoughts, for to think of holiness distinct from man is impossible to the affections” (quoted in ({{harvnb|Tomlinson|1987|p=39}}).}}<br /> | ||

By: [[w:William Blake|William Blake]] ([[w:The | By: [[w:William Blake|William Blake]] ([[w:The Divine Image|1789]])}} | ||

<div style="display: flex; justify-content: center; padding: 25px 0 25px 0;"> | <div style="display: flex; justify-content: center; padding: 25px 0 25px 0;"> | ||

{| style="width: 500px;" | {| style="width: 500px;" | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

To Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love, | To Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love, | ||

All pray in their distress, | All pray in their distress,{{refn|These virtues are longed for by those in ''distress''—or those suffering from a lack of them. The idea seems to be that empathy is a key component of the desire to do what’s right.}} | ||

And to these virtues of delight | And to these virtues of delight | ||

Return their thankfulness. | Return their thankfulness. | ||

Revision as of 09:26, 10 September 2021

|

To Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love, |

Notes & Commentary

- ↑ From Songs of Innocence, 1789. Compare this poem to its contrary, the “The Human Abstract” from Songs of Experience.

In “A Cradle Song,” Blake dramatizes a mother’s love for her child and writes that “we come to know God by ‘honouring his gifts/In other men’”; this theme is developed further here (Tomlinson 1987, p. 38). The human qualities of “Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love” are esteemed by us, so they would be important in God who, in turn, might bestow them upon the devout, as in the third stanza. Blake wrote “Think of a white cloud as being holy, you cannot love it; but think of a holy man within the cloud, love springs up in your thoughts, for to think of holiness distinct from man is impossible to the affections” (quoted in (Tomlinson 1987, p. 39). - ↑ These virtues are longed for by those in distress—or those suffering from a lack of them. The idea seems to be that empathy is a key component of the desire to do what’s right.

Bibliography

- Ackroyd, Peter (1995). Blake: A Biography. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Battenhouse, Henry M. (1958). English Romantic Writers. New York: Barron’s Educational Series, Inc.

- Bloom, Harold (2003). William Blake. Bloom’s Major Poets. New York: Chelsea House.

- Frye, Northrup (1947). Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Gardner, Stanley (1969). Blake. Literary Critiques. New York: Arco.

- Green, Martin Burgess (1972). Cities of Light and Sons of Morning. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Greenblatt, Stephen, ed. (2018). The Norton Anthology of English Literature. The Major Authors. 2 (Tenth ed.). New York: W. W. Norton.

- Makdisi, Saree (2003). "The Political Aesthetic of Blake's Images". In Eaves, Morris. The Cambridge Companion to William Blake. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP. pp. 110–132.

- — (2015). Reading William Blake. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Paulin, Tom (March 3, 2007). "The Invisible Worm". Guardian. Retrieved 2021-09-04.

- Thompson, E. P. (1993). Witness Against the Beast. New York: The New Press.

- Tomlinson, Alan (1987). Song of Innocence and of Experience by William Blake. MacMillan Master Guides. London: MacMillan Education.

- Wolfson, Susan J. (2003). "Blake's Language in Poetic Form". In Eaves, Morris. The Cambridge Companion to William Blake. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP. pp. 63–83.

Links and Web Resources

- Blake at the Internet Archive.

- Blake’s Notebook at the British Museum.

- William Blake Study Questions